Volume 26, No. 3, Art. 11 – September 2025

Experiencing Interconnectedness Through Mindful Inquiry and Meditative Thematic Analysis in Social Science Research

Megan K. Mitchell & Steve Haberlin

Abstract: Contemplative practices, such as mindfulness and meditation, can assist qualitative researchers in discovering novel ways to gather and analyze data and connect with research participants. In this collaborative inquiry, we retrospectively explored how mindful inquiry and contemplative inquiry-inspired approaches impacted our previously conducted studies. Our examination included discussions and comparisons of how we engaged mindfulness-based techniques when generating or analyzing our data. We discovered that these novel approaches enhanced our ability to connect more deeply with both participants and data as compared with using traditional qualitative methods and in the case of meditating with data, creating more open spaces of consciousness to allow insights and themes to flow more freely.

Key words: contemplative inquiry; mindful inquiry; meditative thematic analysis; reflexivity; qualitative methodology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Contemplative Inquiry

3. Mindful Inquiry

4. Our Collaborative Inquiry

5. Positionality

6. Contemplative Inquiry (Example 1)

7. Mindful Inquiry (Example 2)

8. Discussion

8.1 Social justice, integration of mindful and contemplative inquiries, and interconnectedness

8.2 Further Implications

Scholars of contemplative and mindful inquiries have argued for the integration of mindfulness and academia, prompting researchers to engage in philosophical and methodological approaches that align with their values and inner selves (BENTZ & SHAPIRO, 1998; ORELLANA, 2020). The conjoining of these traditions and methods can enhance qualitative research. For the purpose of this article, we are considering "methodology" as the overall approach to research which can include the research paradigm, theoretical justification, philosophical assumptions, and other components, as well as "methods" as specific techniques used (CRESWELL & POTH, 2018). For example, ethnography has its limitations (evidenced through its early formation through initial colonist encounters of the Western and non-Western world) and seeks to understand and perceive "others" on their own terms and from their own unique viewpoints. ORELLANA (2020) argued that contemplative practices, such as mindfulness, can improve researchers' ability to listen more closely, perceive more, and connect in more compassionate ways:

"We can better notice how these arise and change as we engage in relationships and activity in the world and learn to hold our views more lightly, rather than believing everything that we think or letting our perceptions impulsively drive our actions" (p.1). [1]

Likewise, JANESICK (2016, p.20) posited that Eastern traditions such as Zen Buddhism can inform qualitative research, helping to "do no harm" to participants and better understand others through feeling the underlying connectedness. Operating from what he calls an epistemology of love, ZAJONC (2008) described how contemplative inquiry can shift the inquiry from an outer phenomenology (e.g., participants' words, behaviors) to an inner phenomenology (e.g., participants' inner experiences) and progress toward a "meditative attention" that can yield new insights (p.230). For the purposes of this inquiry, while researchers have disagreed over definitions and operationalizing of mindfulness, mindfulness is to be viewed as a quality of awareness (NEALE, 2017) that is associated with intentionally paying attention to the present moment without judgment (KABAT-ZINN, 2013). We define meditation separately as a form of mental training which may or may not include the use of mindfulness. As classified by researchers, commonly practiced meditation styles fall into three general categories: 1. focused awareness (concentration on an image, the breath, or thought), 2. open monitoring (awareness of specific stimuli arising from the senses, body, or brain), and 3. automatic self-transcending (use of a mantra or sound to spontaneously experiencing subtler states) (ROSENTHAL, 2017). [2]

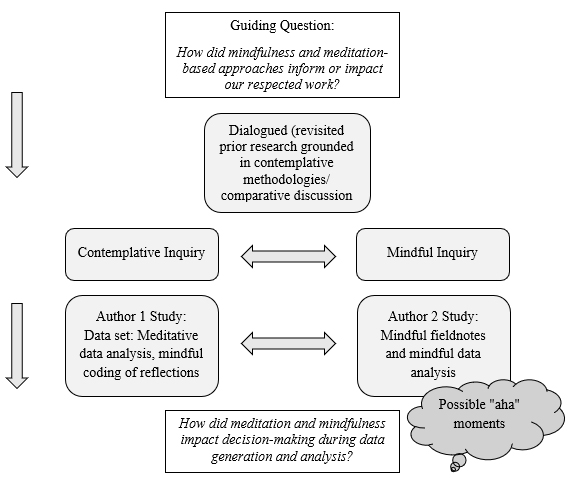

Clearly, contemplative inquiry approaches show promise and should be more fully explored. As scholars explored innovative ways to engage contemplative practices in research, some have experimented with integrating mindfulness techniques into data analysis and theory development (MASON, 2002). As contemplative and mindful inquiries in social science research are vital components of researcher-as-instrument (LINCOLN & GUBA, 1985), we wanted to understand how embracing the essence of these inquiries in education research affected the process of constructing and analyzing data. Thus, the purpose of this article is to illustrate how contemplative inquiry is influential in how scholars conduct qualitative research and to understand how this framework might further innovate methodological techniques and approaches. [3]

Before proceeding, it is important for us to define the term "traditional" as we utilize this within the context of qualitative research. We present "traditional qualitative methodologies" typically as foundational, interpretative approaches commonly used to understand the experiences of participants, and where the researcher's role is to serve as an instrument of inquiry in a naturalistic setting. For instance, this includes well-established frameworks of phenomenology, case study, ground theory, ethnography, and case study. "Traditional" data collection and analysis methods would include interviews, focus groups, participant observation, field notes as well as thematic analysis and manual coding (CRESWELL & POTH, 2018; PATTON, 2015). [4]

In the current work, we explore contemplative qualitative methodology and, later, methods through showcasing two inquiries: First, we describe a study by Steve (the first author), in which mindfulness-based coding and meditation-based analysis were utilized to generate findings. Next, Megan (the second author) describes how she drew on mindful inquiry to guide her approach to data construction during her ethnographic research. To guide our inquiry, we discussed and compared our experiences, seeking possible intersections, e.g., how mindfully informed data collection might complement or shape the use of meditation to engage in thematic analysis. Specifically, our questions for this shared inquiry were:

How does mindfulness as a method of inquiry influence data construction?

How do meditative techniques as methods of inquiry influence data analysis and assist with generating thematic findings?

How might mindful and contemplative inquiries intersect during the data collection and analysis stages of qualitative research? [5]

Our contemplative qualitative collaborative inquiry was guided by two frameworks—contemplative inquiry and mindful inquiry—which were deeply embedded in our research context and shaped how we approached the process. Before sharing methodological examples, we offer an overview of each framework. In Section 2, we elaborate on contemplative inquiry as an epistemological and methodological framework in qualitative research. In Section 3, we define mindful inquiry and explore its intersections with critical social science and ethnographic approaches. In Section 4, we describe our collaborative inquiry process and introduce the two studies that form the foundation of our analysis. In Section 5, we outline our positionality and how it informed the inquiry. In Sections 6 and 7, we present each author's study as an example of contemplative and mindful methodologies in action. We conclude with Section 8, where we discuss cross-cutting findings, implications for social justice, and future directions for contemplative and mindful research. [6]

Contemplative and mindful inquiries as epistemological ways of knowing underlie various approaches that social science researchers use to understand themselves as knowers, the known, and the process of knowing. Some scholars of contemplative and mindful inquiry in educational research commonly draw from constructivist, phenomenological paradigms that knowledge and knowing come from within (e.g., HEIN & AUSTIN, 2001; MILLER, 2016, ZAJONC, 2008). In her writings on contemplative inquiry, JANESICK (2015) proposed how qualitative researchers and Zen Buddhism are complimentary, unpacking how three qualities—impermanence, non-self, and nirvana (enlightenment)—can support qualitative researchers. For example, within Buddhist traditions, the principle of impermanence reflects the view that all things are in constant flux; accordingly, findings generated through qualitative traditions are considered tentative. The concept of non-self or inter-being presumes that everything in the universe is connected, reflecting the role of the qualitative researcher as both instrument and relational presence in the research context. The issue is not simply whether a distinctive attitude or critical mind is present, but that "conceptual distinctions artificially divide the world which is one, and where all the parts are inherently connected" (KONECKI, 2021, p.2). Finally, with nirvana, there is a complete oneness and peace and lack of fear through interconnectedness—again reflecting the deep connection between researcher and study participants. As part of her contemplative inquiry approach, JANESICK (2022) called for researchers to hone intuition and creativity, or "Zenergy," i.e., to "see, hear, and feel who participants in [their] studies really are" (n.p.). [7]

While many mindfulness-based techniques used in the examples presented in this article are grounded in Buddhist traditions, it is important to note that other wisdom and spiritual traditions also espouse notions of interconnectedness among all beings and the environment. For example, in Taoism (WANG, 2022), which predates Buddhism, "the interdependence of everything" (p.187) is constantly engaged in a dynamic relationship. Likewise, Indigenous cultures have long emphasized the significance of connectedness as a central framework for living (MAZZOCCHI, 2020). [8]

In addition to Buddhist and Eastern traditions, scholars across numerous disciplines have emphasized the importance of deep presence and attentiveness in research. For example, SPITTLER (2001) through his concept of dichte Beobachtung [dense observation] in ethnographic fieldwork emphasized careful, sustained attention to embodied experience, aligning with the spirit of contemplative presence without using mindfulness terminology. Similarly, research in performance studies, dance, theater, and somatic education has long explored the epistemological role of the body in knowledge generation and interpretation. Embodiment research challenges dualisms of mind and body and positions the body as a source of insight, not interference (MATÉ, 2011). These diverse traditions illustrate that mindful awareness and reflexive presence are not limited to Buddhist foundations, but are shared across a wide landscape of methodologies that value connection, interdependence, and care. [9]

Another characteristic of contemplative inquiry is critical, first-person inquiry connecting with the Self by immersing in experience and consciousness (ROTH, 2014). One such method of contemplative inquiry is meditation as a conduit to transcending the social self to experience a deeper, salient self with insight and knowing (ZAJONC, 2008). Researchers using contemplative inquiry, like those drawing on other frameworks such as phenomenology, often immerse themselves in experience. This approach can involve meditation and related practices to support the researcher in "participat[ing] more and more fully in the phenomena of consciousness" (p.36). [10]

KONECKI (2021) explained that in reality, research is a dynamic process, with plans often changing mid-stream. Researchers may attempt to bracket their work into stages, but often those stages blend. Maintaining clarity and focus during research involves attending to emotions and bodily sensations, not as distractions but as integral sources of understanding. As MATÉ (2011) and embodiment scholars have argued, the body and mind are not separate but deeply connected; awareness of somatic experience can support more grounded, ethical inquiry. However, it is important to emphasize that for qualitative researchers serving as instruments in their work, the body must not be ignored, as sensations and emotions may not pose problems but rather provide messages to be heeded (ibid.). Thus, for contemplative researchers, observing the workings of the mind and body during the research process is highly significant. As KONECKI (2021) noted, "maintaining a distance from the research fields, concepts, and methods can be mindfully observed and explicated. How do we arrive at conclusions? What are our assumptions before analyzing 'data'? What emotions are aroused in the process?" (p.2). [11]

In addition to observing thoughts and emotions, contemplative inquiry can involve a movement from image to insight, from the gross aspects of an object in the physical world toward its more subtle qualities through inner exploration. To illustrate this, ZAJONC (2008) described the process of investigating a poppy (flower). The observer may begin by noticing the flower's “indented leaves, the fragile petals whose colors wave in the wind, the gold center of each blossom” (p.223). In contemplative inquiry, the researcher is invited to retain the image of the flower and shift inward by “practicing open attention in perfect stillness” (ibid.). With gratitude and patience, the contemplative researcher waits for an inner image, a bodily sensation, or an internal gesture to surface. With continued practice, it may become possible to notice the thought activity that precedes and cultivates the mental image of the flower and eventually transitions toward a deeper awareness of consciousness itself. This process can offer insight into how thoughts arise—often beyond conscious awareness. For example, through “cognitive breathing” (p.107), a meditator gives full attention to content, repeating mantras or focusing on the breath; when attention opens, present-moment awareness becomes accessible. It is from this space—this creative silence—that insights, connections, and ideas may take form. The resulting understanding is not a factual discovery about the flower, but a felt recognition of its vitality, wholeness, and relational presence—an embodied sense of being-with rather than knowing-about. [12]

BENTZ and SHAPIRO (1998) posited mindful inquiry as a framework of Western knowledge traditions: Critical social science, phenomenology, hermeneutics, and the Eastern tradition of Buddhism. The rationale for a mindful research approach is to assist scholar-practitioners with navigating vast amounts of knowledge, and onslaughts of information, as they work to derive meaning and put that knowledge into practice, ideally not losing their identity in the process. As BENTZ and SHAPIRO wrote in the 1990s, even before the prevalence of 24-hour news and social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and streaming services like Netflix, "it is easy to become engulfed and overwhelmed by the mass of available information and the Internet" (p.36). Mindful inquiry approaches participants with care and acceptance but is also described as a creative act, "it seeks not only to discover or record what is there but to allow what is there to manifest in a new way, to come forward in its 'shining'" (p.54). Specifically, mindful inquiry shares certain principles with Buddhism: the importance of thought itself, the intention to alleviate suffering, the ability to hold or accept multiple, diverse views and perspectives, and the notion of openness or underlying awareness. [13]

Some scholars have explored how mindful inquiry can support researchers in stepping outside of themselves to better understand the lifeworlds of others (AGAR, 1994, 2006a). Ethnographers, for instance, seek to learn from and with people, the insiders, of a culture-sharing group. They want to make visible cultural knowledge and norms as culture is constructed through social processes, interconnected to larger historical sociocultural systems. ORELLANA (2020) presented mindful ethnography as an approach for seeing and understanding sociocultural structures. This approach supports researchers in entering the field without predefined research questions or orienting frameworks, and instead being present in each moment as participant observers connecting with people through openness and care. [14]

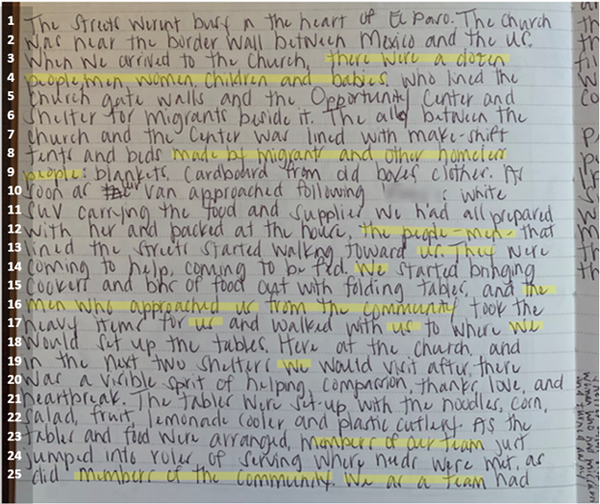

Mindful inquiry is an epistemological approach that involves paying attention, without judgment, to the unfolding moment-by-moment experience. According to ORELLANA (pp.66-67), a "mind-heart-activity triad" can serve as an orienting framework for mindful ethnography. In this model, researchers draw from a fusion of logic and spiritual knowing to engage with communities in holistic and reflective ways. Social science researchers can embrace this triad as a logic of head-heart inquiry to activities of observing, participating in fieldwork, writing up descriptive and reflective notes, analyzing, and composing final reports. While the word "activity" implies agentic, physical movement, activity as doing also includes being still, listening, suspending thoughts with presence, and meditative sitting through the mind's and heart's eyes; experience is not neutral. In this regard, contemplative and mindful inquiries are interconnected through various qualitative approaches used in social science research. [15]

When it comes to mindful inquiry and generating records in ethnographic fieldwork, writing descriptive fieldnotes can be an overwhelming experience for qualitative researchers (EMERSON, FRETZ & SHAW, 2011; HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 2019). In ethnographic studies, for example, research questions and conceptual frameworks may not develop until after extended periods are spent in the field observing, writing field notes, and reflecting (DELAMONT, 2008). How, then, do researchers make decisions about what to write in their field notes? Considering the non-linearity of ethnographic research and its abductive logic of inquiry (AGAR, 2004), the choices ethnographers make about what to write, what not to write, and their use of language to capture telling moments of a culture-sharing group are noteworthy methodological decisions. In time, seemingly mundane actions and interactions amongst cultural members may become the most relevant patterns of insight for understanding larger sociocultural influences, historical contexts, and power structures (SPRADLEY, 2016 [1980]). Because the research process is non-linear, transparency of methodological decisions is ever more important in writing ethnographic field notes. [16]

Mindfulness in writing field notes is more than a method of inquiry. Rather, it is an epistemological way of being in the world (ORELLANA, 2020), with and within communities and sociocultural structures that shape lives. Engaging in mindful inquiry while in the field writing descriptive notes, expanding on those field notes after the fact, and then reflecting on what was (and was not) written can deepen a researcher's reflexive awareness of the conscious and unconscious decisions they make about the language they use and what this signals about their assumptions and taken-for-granted understandings. Embedded in every word written on pages of field notes are value-laden methodological choices made by the researcher-as-instrument (ibid.). By practicing mindfulness to examine the language used in field notes, researchers can reflexively explore their subconscious subjectivities in relation to the data, the people, and the political underpinnings of their research. This, in turn, can influence methodological decisions in future fieldwork endeavors: Researchers’ emic and etic points of view (AGAR, 2006b), how they enter, occupy, and leave a fieldwork setting (HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 2019), their relationship to the people and inanimate objects within the surrounding environment, their words and positionings used when writing field notes and reflective memos, and how data generated by and with cultural members are analyzed and portrayed in the final reports (ORELLANA, 2020). [17]

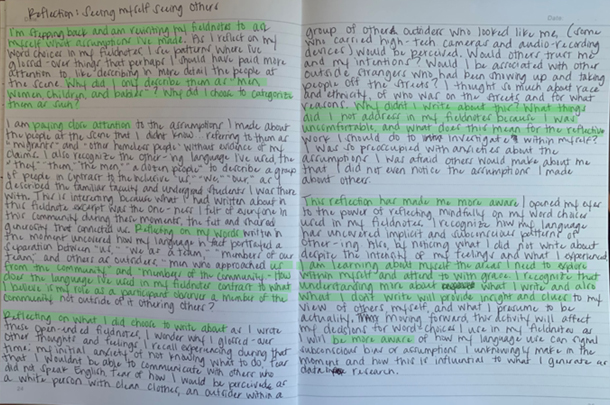

Collaborative inquiry, originally stemming from co-operative inquiry, dates back several decades as a participatory research method (HERON, 1996). Grounded in humanistic psychology, co-operative inquiry involves planning action, taking action, observing and reflecting on outcomes, and revision based on learning. Heron's work was later expanded upon, evolving into collaborative inquiry, a broader term including co-operative inquiry but less structured and focused on democratizing knowledge production and participants as equal contributors (REASON & ROWAN, 1981). [18]

To understand how contemplative and mindful inquiries informed how we constructed and analyzed data in our research, we engaged in collaborative inquiry and looked back at our earlier studies to understand how the use of mindfulness and meditation methods was influential to the development of our findings. Together, we collaborated on possible connections between mindful inquiry-informed data construction in the field and meditative data analysis. For example, we analyzed how these frameworks influenced or changed traditional approaches to coding and theming data in qualitative research as well as how these approaches might have impacted our interactions with participants and our identities as researchers. We first dialogued about our ideas for this inquiry, then drew from datasets of our earlier studies where we used contemplative and mindfulness methods as modes of inquiry to construct and analyze data. We each examined how we came to decisions, focusing on our data construction and analysis to understand how and in what ways contemplative and mindful inquiries as orienting frameworks were influential and consequential to our research. We sought possible similarities on how mindful and contemplative inquiries shaped our interactions with data but also possibly spurred reimagined ways of working as qualitative researchers. We also shared major insights (aha moments) that surfaced during our work and held a comparative discussion. A visual representation of this process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Collaborative inquiry process [19]

Our collaborative process is shown in Figure 1, beginning with early dialogue about how our framings of contemplative and mindful inquiries shaped our data generation and analysis, influenced our interactions with participants, and informed our identities as researchers. The guiding question we asked from these discussions is shown in the box at the top of the figure. The two arrows pointing in a downward direction on the left side of Figure 1 represent the flow of our investigative process into how mindfulness and meditation-based approaches informed or impacted our studies. The two-sided arrow between Contemplative and Mindful inquiry represents an interconnection between our conceptual framings in that we were guided by tenets of each framework to analyze data we generated for our respective studies. The two-sided arrow between Steve's study and Megan's study represents how we each engaged with contemplative and mindful inquiry in distinct research contexts. Through this process, we each developed deeper connections to ourselves as researchers, to our participants, to our data, and to our evolving understandings of meditative and mindful inquiry throughout the research and our comparative reflections. [20]

As qualitative researchers, we uphold transparency in our work and acknowledge that our research is inherently value-laden, as discussed by BREUER (2000). Thus, before presenting our examples, we believe it is pertinent to identify our positionality within the context of this inquiry, including how we came to explore non-traditional, contemplative practices such as mindfulness as it relates to our research methodology. [21]

Steve is a 52-year-old, white male, who works as an assistant professor at a large, research-1 university. His background includes teaching in K-12 settings before moving to higher education, where he served as faculty in a teacher preparation program. Steve is an Italian American, born and raised in middle class neighborhoods in New England, who attended public schools. However, his worldview of education has been influenced by more holistic approaches, which cultivate the whole-person. For the past five years, Steve's research has focused heavily on the use of meditation and mindfulness practices in academia, particularly how these practices impact undergraduates. His personal contemplative practice involves engaging in daily meditation, mainly transcendental meditation—a mantra-based method- for the past 25 years. When designing his dissertation study, which focused on the use of mindfulness-based techniques while supervising teacher candidates, it seemed appropriate to experiment with meditation, "one of the oldest forms of research" (MILLER, 2016, p.128) when analyzing data. Steve believed that entering a state of restful awareness through meditation might assist in allowing insights to emerge more spontaneously. [22]

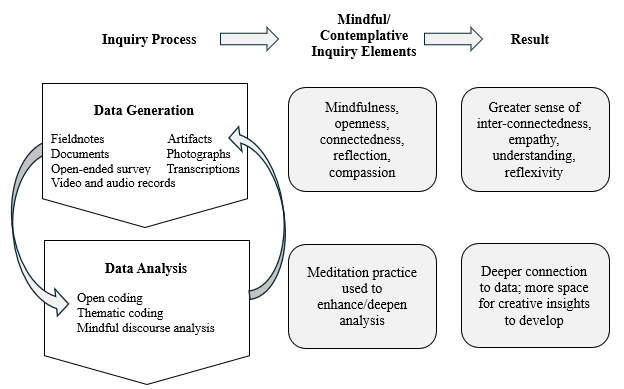

Megan is a White American scholar born and raised in middle class neighborhoods in the Southeastern United States, with cultural roots in Northwestern and Southern European heritage. Her academic and professional path has been shaped by experiences in team-based settings, including teaching as an assistant professor, coaching sports, and working in higher education advising. At the time of this collaborative inquiry, she was a doctoral student at the same university as Steve. Trained in education research with a specialization in qualitative methodologies, she draws on critical and interpretive traditions that position research as relational, reflective, and justice oriented. Her commitments to education as a human right, not a privilege, are rooted in her own experiences attending public schools and guide her work with and alongside students, faculty, and communities striving toward equity. These values shape the questions she asks, the methods she chooses, and her view of research as a catalyst for social transformation. Her research continues to center on doctoral education, classroom culture, and ethnographic approaches to studying learning and participation. Through these inquiries, she engages with culture as a dynamic, evolving process (STREET, 1993), shaped by the histories, interactions, and broader sociocultural systems individuals bring with them. Grounded in an epistemological stance that centers presence, openness, and interconnectedness (ORELLANA, 2020), she approaches participant observation with an ethic of attentiveness. She integrates mindfulness practices as part of her reflexive process, attuning to her role and relationships during fieldwork, analysis, and representation, to stay present to tensions, assumptions, and shifting understandings as they arise. [23]

6. Contemplative Inquiry (Example 1)

The first study presented here as an example of exploring contemplative practices and mindful inquiry within qualitative methodology comes from Steve, who revisited research completed during his dissertation work (HABERLIN, 2019). Steve conducted a self-study to understand how mindfulness-based practices might inform his instructional supervisory role which involved coaching teacher candidates in their final year of a teacher preparation university program. Their fieldwork involved student teaching at a local elementary school. Steve's data collection involved completing observational notes while observing the teacher candidates in the classroom and following conferencing with them and completing a researcher's journal each week during the course of an academic semester. To gather additional qualitative data, weekly open-ended electronic surveys were also completed by teacher candidates. While collecting data, Steve experimented with meditative thematic analysis (MILLER, 2016; ROMERO, 2016). This involved reviewing his data and then immediately meditating using vipassana or mantra-based meditation. The breath or mantra was the main focus, though the data content remained in the back of his mind. In time, the content minimized and gradually disappeared, like dropping a pebble in deep water and watching it vanish. Steve did not try to control the process but allowed the meditation to take its course. Upon opening his eyes, he wrote reflective memos on his experiences. The memos often took the form of free-style prose, stream-of-consciousness jottings, or poetry, resonating with NGUYEN's (2018) work which positions poetic reflection as a valid conduit for insight and deepened understanding in qualitative research. Table 1 outlines Steve's specific process of meditating with the data.

|

Step |

Rationale |

Examples |

|

Read over data and research questions. |

Provide an object of focus for the meditation. |

Review observational notes from Week 2. Reflect on research questions for the study (e.g., how did mindfulness practice inform my supervision role this week?) |

|

Enter a state of meditation by practicing breath meditation or mantra-based meditation. |

Bring the object of focus (the data) to deeper, more subtle states of consciousness. |

Sit comfortably. Close eyes. Bring awareness to the flow of breath as it enters and leaves the nostril area. |

|

Remain present with the object of attention As ROMERO suggested (2016, p.101), "as the meaning of the words begins to penetrate, let the words drop away, and rest in (the meaning). Become familiar with that meaning as it penetrates." |

Practice "letting go" of the data and the search for themes/findings. Allow the insights to emerge on their own accord. |

Observe any thoughts, including those about the data, without judgment or reacting. Continue to gently return awareness to the breath or mantra. |

|

After 15-20 minutes of meditation, arise with meaning in my heart and mind. Immediately, write a reflection in whatever form comes to mind. |

To capture any ideas and notes from this space of meditative openness and awareness. |

Open the eyes, sit at the nearby laptop, and type any ideas or insights that come to mind. |

Table 1: Meditative data analysis [24]

Next, Steve practiced a form of mindful inquiry by open coding across the memos (written after collecting data and engaging in meditation), adhering to MILLER's (2016) meditative attitudes, including non-judgmental observation, impartial watchfulness, and present-time awareness. Using mindfulness-based coding, the aim was to "see phenomena as clearly as possible without distortion" (p.131). It should be acknowledged that “seeing without distortion" is not possible, as distortion is needed to create a physical form, which then creates perspective. Nevertheless, the mindful coding approach provided increased awareness of the researcher's particular perspective, shaped by previous experiences and worldview. Often, the mindful coding process—the quality of non-judgmental awareness brought to the data-was experienced within the themes as well (Table 2). [25]

Based on this initial mindful coding, Steve constructed larger categories of meaning and then wrote thematic sentences (Table 2).

|

Categories Generated From Meditative Memos |

Conversion to Thematic Sentences |

Examples/Insights |

|

Living Zen

|

Living Zen means not trying to intellectually implement it |

During mindful coding (without judgment, experienced less intellectualizing, allowing to recognize the category and theme. |

|

Anxiety/Nervousness |

Anxiety is something I experienced when becoming more mindful |

Being more present with data (codes) became more aware of the anxiety experienced during the data collection process. |

|

Flowing/Moving Between |

Flowing is an experience I had during supervision |

Coding with less resistance (judgment, analytical thinking) encouraged seeing this flow in the data. |

|

Connection With Mentor Teachers |

Connection with mentor teachers means I was more interconnected with them |

Removing judgment and ego, could recognize this shortcoming. |

|

Enhancement of Observation Cycle |

Enhancement of the observation cycle is what happened when enacting Zen |

Mindful coding—enacting watchfulness-encouraged this insight. |

|

Noticing Stress/Emotional Difficulties |

Noticing stress/emotional difficulties among the teacher candidates is what I experienced when becoming more mindful |

Becoming more aware during coding of memos assisted in this insight; becoming more mindful in coding provided a similar benefit to becoming more mindful with others and their emotionality. |

|

Present-Moment Awareness |

Present-moment awareness is what I came to believe about supervision |

The present-moment awareness practiced with the coding was the same quality brought to supervision practice as a whole. |

|

Revised Purpose of Supervision |

Revised purpose of supervision means I saw my role/responsibility differently |

Mindful coding helped bring less judgmental perspective—this contributed to recognizing revised perspective of supervisory role. |

Table 2: Mindful coding example from Steve's research [26]

During this process of meditative analysis and mindful inquiry, Steve experienced a deepening awareness and enhanced connection and sensitivity to participants as well as intimacy with the data. While Steve went through varied insights depending on the particular data reviewed and the week engaging in analysis, an example of an insight from the meditation process was: When performing mindfulness practices (e.g., mindful walking, mindful breathing) during data collection, he grew more aware of his relationships to "others" in the study, as well as their emotions and reactions in the field. For example, when completing his dissertation research, in the fourth thematic sentence (Table 2), Steve wrote about experiencing an enhanced sense of connectedness with participants but also realized that he lacked the stronger bonds that the participants enjoyed with their mentor teachers. [27]

Steve also experienced deeper connections with participants while meditating with the data. For instance, he reflected several times on the sensitive nature of observing teacher candidates in their assigned environments, collecting data in the context of individuals often challenged beyond their current skill set and knowledge levels. Steve had a similar experience to GONZÁLEZ-LÓPEZ (2011), who wrote she was "keenly aware of and present in the social contexts and circumstances surrounding the everyday life experiences of the people who participate in my research" (p.448). Specifically, some teacher candidates had emotional breakdowns during time spent as their supervisor, and Steve contemplated whether to report such matters and how to keep their identities protected. [28]

Outside of the field, during data analysis, Steve also noted a deepened connection to the data itself, a different quality. JACOBS (2003) discussed neurological processes that occur during meditation: High-active beta waves decrease to a non-arousal state where one may experience flow, a physiological state more conducive for creative ideas to surface to consciousness. According to neuroscience research, mantra meditation such as the practice Steve used during his meditative analysis can increase blood flow to the brain's prefrontal cortex and elevate Alpha 1 brain waves, which are associated with creativity and a state of restful alertness (ROSENTHAL, 2017). [29]

McDONALD (2005) explained that meditation helps to stabilize the mind, and consequently, the meditator can begin to develop insight and achieve "the correct understanding of how things are" (p.171). During meditation, an individual moves past conditioned patterns and behaviors, gaining conceptual clarity which "brings direct and intuitive knowing," and the practitioner reaches more subtle levels of conceptual thought; thus, these thoughts are "more potent than our thoughts during day-to-day life" (ibid.). In retrospect, the meditative analysis process described in Table 1 aligns with ZAJONC's (2008) contemplative model of moving from image to insight—in Steve's case, from the data (as image) to thematic findings (as insight). [30]

Interestingly, we believe that meditating with data added a new dimension to thematic analysis, one that allowed the information to settle within a calmer, more contemplative space. This provided more fertile ground for insights, ideas, and revelations to happen, more time and space for those "aha" moments (TOPOLINSKI & REBER, 2010). For instance, reaching a place of creative silence (ZAJONC, 2008), Steve experienced what seemed like transcending the traditional coding process and theme-jumping, where on at least one occasion, a fully developed theme flashed into his conscious mind. Specifically, this happened when Steve studied qualitative survey data, where teacher candidates explained their relationship to himself, as an instructional supervisor, and to their mentor teachers, the experienced teachers who volunteered to guide them in their assigned school field placements. Rather than proceed through the traditional coding process, where Steve would have sought out patterns and created organizational codes and eventually used these larger codes to create themes, a completed theme "jumped" into his awareness—thus, circumventing the usual steps. Of course, this did not always happen when emerging from the meditative analysis, but this experience opened his mind as to what might be possible when it comes to qualitative data analysis. Steve's meditative analysis experience might best be summed up by a statement from KABAT-ZINN (2001):

"Inquiry doesn't mean looking for answers, especially quick answers which come out of superficial thinking. It means asking without answers, just pondering the questions, carrying the wonder with you, letting it percolate, bubble, cook, ripen, come in and out of awareness" (p.240). [31]

7. Mindful Inquiry (Example 2)

Megan presents the second study as an example of exploring how mindful inquiry as an epistemology was influential to data construction. This study drew from ethnographic research Megan conducted while engaging in immersive, community-based participatory fieldwork with faculty and undergraduate students focused on human rights and social justice issues. During this study, Megan used ORELLANA's (2020) principles of mindful ethnography to guide her process of generating data. Focused on simply being in the present moment with the data while generating records in the field and mindfully reflecting on field notes deepened her engagement with reflexivity throughout the study. This shaped her methodological decisions during the research process. [32]

The data presented in this section are drawn from a week-long period of intensive ethnographic fieldwork conducted in a U.S. border region. This fieldwork was part of a larger ethnographic study that explored how university students, faculty, and staff engaged in community-based educational experiences oriented toward social justice. The broader study focused on understanding how these social actors negotiated their roles and responsibilities while participating in fieldwork that involved direct engagement with communities facing structural marginalization. The research examined how participants made sense of their actions, positionalities, and commitments within contested sociopolitical contexts. Megan served as a participant observer during the fieldwork, which included daily engagement in the field, detailed descriptive field notes, and reflective journaling. Data were generated through participant observations, analytic memos, and informal meeting conversations among the university group to explore how educational actors experienced and responded to the complexities of justice-oriented community work. [33]

Pictured in Figure 2 is an excerpt of Megan's field notes, in which she had engaged with mindful inquiry by revisiting her field notes as an outsider to see herself seeing others. ORELLANA described how mindfully reflecting on words researchers write in field notes can attune them to their implicit assumptions and presuppositions, generating reflexive awareness of Self and others.

Figure 2: An excerpt from Megan's field notes1) [34]

The yellow lines in Figure 2 were drawn by Megan during an evening of mindful reflection, as she reread the field notes she had written earlier that day following her time in the field. In this moment of contemplative engagement, she applied mindful coding (MILLER, 2016) to examine how her language reflected implicit assumptions and subjectivities. This reflective pause became part of an ongoing practice of returning to field notes with mindful awareness, allowing her to observe not just the data, but also her evolving role within the research. The column of numbers on the left side of the image was added to each line of text in the excerpt to further examine how engaging with mindful inquiry can provide reflexive insight into her positionality and subconscious subjectivities through her use of language. As a participant observer in the ethnographic study, Megan used mindful inquiry to identify and better understand patterns in her fieldnote language, including instances of othering she had unknowingly written at the time (Table 3).

|

Lines |

Excerpt of Fieldnote Entry |

What the Language Signals |

|

3-4 |

"When we arrived to the church, there were a dozen people: men, women, children, and babies ,,," |

Use of word "we" indicates a group identity Megan saw herself as part of, separate from the "men, women, children, and babies" at the church.

|

|

8-9 |

"The alley between the church and the center was lined with make-shift tents and beds made by migrants and other homeless people ,,," |

Megan recognized the assumptions she made about the objects and artifacts present in the fieldwork setting, and who had created what she assumed were "make-shift tents and beds." The statement "migrants and other homeless people" uncovers an assumption Megan made that migrants are homeless. Connects to the group of "men, women, children, and babies" identified in lines 3-4, separate from Megan's self-identified group. |

|

12-14 |

",,, SUV carrying the food and supplies we had all prepared with her and packed at the house, the people—men—who lined the streets started walking toward us. They were coming to help, coming to be fed." |

Words "we," and "us," indicate Megan identifies herself as part of a group separate from "the people—men," and "they." Megan indicates a power differential between the group she positions herself as part of separate from "the people — men—that lined the streets started walking toward us." "They" were coming to her group "to be fed," signaling the power differential between the two groups. |

|

15-19 |

",,, the men who approached us from the community took the heavy items for us and walked with us to where we would set up ,,," |

"the men who approached us," "took the heavy items for us," and "walked with us to where we would set up" indicates the separation of two groups.

|

|

23-25 |

",,, members of our team just jumped into roles of serving,,, as did members of the community. We as a team ,,," |

Use of words "members of our team" and "We as a team" reflect Megan's personal conceptions of a group of people working together. Megan recognized how her personal background in team sports shaped how she interpreted actions and interactions amongst group members and that this prior knowledge could impose or assume meaning onto the actions, interactions, and intents of others. Identifying two separate groups: "members of our team" and "members of the community" recreating a single group identity of "We as a team ,,," |

Table 3: Megan's mindful inquiry of the fieldnote excerpt [35]

The first and second columns on the left in Table 3 indicate what lines of text are being analyzed from the image of Megan's field notes on Figure 2. The furthest right column in the table contains the discourse analysis Megan conducted as part of her mindful inquiry. Direct quotes in Table 3 are indicated by the double quotations. The ellipses ",,," indicate there are words before or after the excerpt text not included in the table. Italicized words indicate the keywords of analysis in the third column on the right. As shown in the table, Megan's engagement with mindful inquiry while reflecting on her ethnographic field notes led her to a deepening awareness of her unconscious subjectivities and other-ing language by examining closely the inferences made through her word choices. [36]

After highlighting and analyzing her field notes, Megan wrote a reflective excerpt (Figure 3) using mindful inquiry as an epistemology: Stepping back to observe herself, introspection, and asking investigative questions to prompt deeper consideration (ORELLANA, 2020; ZAJONC, 2016).

Figure 3: Megan's reflective entry written after mindful inquiry of the fieldnote excerpt [37]

Figure 3 presents the entry Megan wrote following a period of mindful contemplation. After writing the entry, Megan highlighted in green the areas where she continued to engage with mindful inquiry. For example, she posed a series of self-directed questions such as: "Why didn't I write about this?" She questioned her subliminal categorization of people within the culture-sharing group which she was a part of: "Why did I choose to categorize them as such?" This demonstrates how, through this process, she cultivated deeper awareness of her implicit assumptions (KONECKI, 2019), how these influenced the way she represented people in her field notes, and how she situated herself within the community’s culture. Before engaging in this activity, she was unaware of the other-ing inferences (NAROPA, 2017) embedded in her field notes. Because of mindful inquiry, an awareness of other-ing rose to the surface of her consciousness while reflecting on her field notes like steam rises from asphalt on a hot summer day. This deepening understanding led to greater awareness of how her language portrays and positions people. With this greater awareness, she embraced mindful inquiry as an epistemology, a way of being a participant observer in and with the world where she was present with people and her surroundings in the proceeding of fieldwork ventures. The process of mindfully sitting with the data introspectively changed her, which shaped her process of generating data moving forward. [38]

Our collaborative inquiry involved first, revisiting our prior research involving contemplative and mindful inquiry-based approaches and moving towards comparing our individual experiences to find commonalities and "aha" moments. Our collaboration produced two key findings: First, using contemplative and mindful inquiries as orienting frameworks for how we constructed and analyzed data led us to deeper understandings of Self as researchers and supported a deeper connection to the participants and our work. Of course, given less time, these relationships with these three aspects could have differed. For example, less time with participants or data might have de-intensified our connections. Second, engaging in mindfulness and meditation-informed inquiry could promote mental states that are conducive to recognizing significant insights and themes within qualitative data. [39]

From our comparative discussions, we had both experienced that using mindful and contemplative inquiries impacted the outcomes of our studies because of how it changed our processes for constructing and/or analyzing data. Rather than approaching our fieldwork and data in search of answers to our questions, we centered our focus on simply being in the present moment. In other words, rather than seeking to shape the research, the research shaped us. The groundwork we had laid from prior reading, writing, and thinking had created fertile ground for awareness to manifest and connect to consciousness as we engaged with mindful and contemplative inquiries during our research processes. For both of us, contemplative and mindful inquiries were consequential to the development of our studies, opening our awareness and attention to the ways our egoic selves created separateness from participants, and awakening us to connect with them moment-by-moment. As evidenced in examples 1 and 2, we experienced an enriched sense of connectedness with our participants and the research process, much the same way that JANESICK (2016) has purported in that Eastern traditions can inform qualitative research in helping researchers deeply understand others through feeling our underlying connectedness. That is not to say that other non-traditional methods, besides mindfulness and meditation, may not also enhance the qualitative researcher's work. For instance, ancient Chinese practices such as Qigong and Tai Chi, indigenous practices, and movement-based arts, such as dance, might also bring much value, and we encourage research into these areas as well. [40]

Nevertheless, our insights represent our "truths." Notions of experiencing deeper connection with data or participants, for instance, are subjective and shaped by our individual perspectives, experiences, and social contexts featured within this research. Thus, we do not attempt to provide "facts" in our work but rather share meaning we uncovered through our mindful and contemplative-inspired experiences. [41]

Of course, there is also the issue of an inherent contradiction for researchers between "being" and "doing" that must be considered in light of contemplative-inspired qualitative research. For instance, researchers engaged in phenomenological inquiry often experience a tension between carrying out research activities (such as using interview protocols and coding) and remaining fully present with participants during their lived experiences (VAN MANEN, 2017). Practices such as mindful observation and mindful coding could intensify this sense of being, and researchers would do well to be aware of this change. [42]

Collaborating together on our insights, we juxtapose how mindful and contemplative inquiry in our methods of data construction and analysis go deeper than traditional methods. Engaging mindfulness methods while constructing data generated a deepening level of reflexivity that shaped the data with more intimate, vulnerable connections to participants and community cultural meaning. Additionally, contemplative inquiry through meditative methods brought Steve closer to the data and created internal spaciousness for creative silence from which themes emerged more spontaneously. Whether mindful inquiry-based coding fostered enhanced meditative analysis—or vice-versa, additional research is needed, though the methodologies seem complementary. Overall, Steve and Megan experienced enhanced interconnectedness with the research process and the people involved with that work. Figure 4 depicts how our inquiries intersected and provided a conceptual pathway for fellow qualitative scholars to perhaps perceive how contemplative and mindful inquiry frameworks and methods might support their work.

Figure 4: A contemplative/mindful approach to qualitative research [43]

Shown in Figure 4 is the contemplative and mindful inquiry process, illustrated in the furthest left column. Within the inquiry process are records from which to generate data in qualitative studies, and methods of analysis. The cyclical arrows connecting Data Collection and Data Analysis show that mindful and contemplative inquiries in both phases of a research project can inform and influence the other with potential, as generating and analyzing data can be a non-linear process (AGAR, 2004; HAMMERSLEY & ATKINSON, 2019). As shown in the middle column in Figure 4, both mindful inquiry and contemplative inquiry infused our work with qualities (e.g., openness, deepening awareness through constant reflexivity, compassion) that might normally not exist or at least not to such a degree in our research. For example, as illustrated in the furthest right column, engaging in mindful field note-taking as well as mindful data analysis helped us maintain the observant, rational mind needed to conduct research but also did not allow conceptual distinctions to make us feel separate from participants or our experiences (KONECKI, 2021). [44]

Nevertheless, as researchers, we should address possible limitations inherent in our work. First, our experiences, such as enriched connection to data and participants, is filtered by our own positionality, including our background, culture, and worldview. Other researchers experimenting with similar methods might have different experiences. For example, did Steve's extensive meditation background filter his experiences and perceptions of engaging with data using contemplative practices? In other words, might a researcher with little or no meditation experience describe dissimilar effects, including those that are more difficult or disorienting? Another limitation of our collaborative inquiry is that our combined work and findings were based on previous research, conducted in particular settings, with specific participants. Collaborative inquiry based on different studies, using different participants, could likely produce different insights. [45]

Regarding the use of mindful inquiry and contemplative inquiry-inspired qualitative research in general, several challenges immediately present themselves: 1. what if a researcher lacks familiarity or training in mindfulness-based or meditation-based practices? 2. Relatedly, what if the researcher is not comfortable with such an approach? Might this produce adverse effects for both themselves and participants? 3. Critics might argue that we—and others embracing contemplative and mindful inquiry—are culturally appropriating Eastern traditions, such as Buddhism, in the midst of engaging in this work. In response to the first limitation, following the general consensus of contemplative scholars and meditation teachers (BARBEZAT & BUSH, 2013; BURROWS, 2017), we advise that researchers consider establishing a personal mindfulness or meditation practice. This would generate first-hand experience with these approaches and would serve as a basis for embodying mindfulness and meditative states during research. For example, Steve believed he was able to experiment with meditative analysis due to decades of meditation practice which served as a foundation. Of course, decades of practice is not necessary—or practical—but some regular, direct experience is reasonable. Formal training, such as the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MSBR) program, can be completed to provide aspiring contemplative-mindful inquiry-based researchers with more background and experience with mindfulness practices. In addition, they might consider joining professional associations, such as the International Society for Contemplative Research (ISCR) or the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society to become more versed in contemplative-based practices and collaborate with like-minded scholars. [46]

To address the second limitation, we believe that qualitative researchers would do best to utilize methodologies that feel comfortable and that call upon their strengths and unique backgrounds. Hence, mindful and contemplative inquiry-based methods, as described in this article, may not be suitable or appropriate. Perhaps they have found other approaches that enhance their work, for example, creating more connectedness with participants. We do not view these ideas as one-size-fits-all. [47]

Finally, anticipating that some scholars might argue that we are culturally appropriating contemplative traditions in the pursuit of embracing these frameworks, we would like to address this issue. While the scope of this article does not provide adequate space to fully unpack this topic, it should be noted that some academics have argued that, for example, mindfulness programs cannot be "fully secular" as mindfulness methods are based on Buddhist ethics (BROWN, 2017, p.45). Others insist that mindfulness and meditation have been appropriated or commoditized in society (HYLAND, 2017; PURSER, 2019). We believe that contemplative scholars must seek their own path and knowledge regarding the historical significance and cultural context of the traditions and practices they experiment with during research. That said, we also strongly encourage the desire to more fully understand the cultural and spiritual roots that undergird their chosen contemplative approach. For example, MEHTA and TALWAR (2022) described a framework called integrative mindfulness (IM), which is intended to support academics and others in adopting a more holistic mindset that encompasses all aspects of mindful living. IM is defined as "the recognition and implementation of spiritual and cultural wisdom, including (but not limited to) Buddhist and Hindu principles in the Euro-American context to promote culturally humble contemplative practices with the central intention to understand and transcend suffering" (p.6). In practice, this involves mindfulness-based program teachers and scholars studying the theoretical framework of Buddhism (the Four Noble Truths2)) on which Buddhist mindfulness "rests," and recognizes the major role that suffering and the cessation of suffering play in this tradition (BODHI, 2000). Furthermore, contemplative scholars can learn to expand their view beyond the individual to the community and also the events that impact us all and lead to suffering. MEHTA and TALWAR (2022) emphasized the importance of recognizing the spiritual and cultural value assigned to the interdependent self. They proposed that integrative mindfulness offers a pathway for recognizing shared humanity and non-separation between self and other (p.11). While only one example, such a framework can help guide contemplative researchers to avoid misappropriation. This viewpoint also strongly coincides with the enhanced interconnectedness both Steve and Megan experienced when engaging in mindful and contemplative inquiry. [48]

8.1 Social justice, integration of mindful and contemplative inquiries, and interconnectedness

This section addresses how mindful and contemplative inquiries align with social justice commitments in qualitative research. Drawing from key scholars in these domains, we examine how presence, attentiveness, and relational accountability shape our ethical and methodological decisions. [49]

Philosophical and conceptual frameworks of social justice question the imbalances and inequitable distributions of economic, political, religious, and educational rights, privileges, and opportunities afforded to all living beings within a society (RAWLS, 2005 [1971]). Contemporary social justice movements seek equity and inclusivity for historically and presently oppressed or marginalized groups. These movements are grounded in community, relationships, love, and transformative action. Similarly, mindful and contemplative inquiries ask researchers to attend with intention and care to what is happening within and around them. These practices call us to recognize the ways in which our thoughts, words, and actions either uphold or dismantle structures of exclusion. [50]

As researchers, integrating mindful and contemplative practices into our work opens us to bear witness to the lives of others. Researchers create records of human lives based on their words, their eyewitness testimonies (ORELLANA, 2020). In Table 1, Steve's meditation with the data opened his awareness to participant meaning and relationships through reflective writing. Megan's mindful analysis of field notes led her to recognize her own assumptions and the language she used, aligning with NAPORA's (2017) guidance to observe with non-judgment and interrogate moments of othering. This deepened her understanding of how discourse reflects power, and the social responsibility researchers carry to listen deeply and ethically represent others. These examples reflect JANESICK's (2016) call for researchers to practice attentiveness, and echo BHATTACHARYA's and COCHRANE's (2017) work on contemplative approaches rooted in equity and relationality. [51]

From a social justice lens, we asked ourselves: How do our positionalities influence the words we jot on the pages of our inquiries? In choosing the words we do, whose voices are uplifted and whose are quieted? How are lives represented, and in what ways do our words call for action? [52]

Scholars of transformative and decolonizing research (COHENMILLER & BOIVIN, 2021; MERTENS, 2007; SMITH, 2012) remind us that every methodological choice is also an ethical one. Qualitative inquiry must be guided by justice, care, and cultural respect. In social justice movements and research alike, no word is neutral. Every word holds power to reinforce or disrupt the status quo. [53]

In academia, researchers are often trained to be problem-seekers rather than problem-solvers (WATTS, 2009). Yet mindful and contemplative inquiries encourage us to move toward transformative action. In our work, contemplative practices helped us verify how our words were used for representation. Member-checking and member reflections were not only methods of triangulation but also of accountability. As ORELLANA (2020) noted, participants are some of the best people to hold us accountable for the truth and kindness of our representations. When we bear witness to others' suffering and interconnectedness, we are moved to compassion. Mindful inquiry can create space for this compassion to take root and flourish. Our work, then, contributes to broader efforts to instigate social change and illuminate the voices of underrepresented and marginalized communities. [54]

Researching with mindful inquiry and contemplative inquiry-based approaches prompted us to experience the research process, relationship with data, and connect with participants in altered ways. For instance, we became more aware of the mental and emotional states of participants and, in the case of Steve, meditating with data seemed to allow insights to flow more easily and in their own time. However, we wonder if other practices that train presence and awareness (i.e., poetry, painting, and other creative endeavors, movement-based such as dance and the martial arts) might also encourage similar experiences and insights for qualitative researchers? We think by sharing our collaborative inquiry, fellow qualitative researchers might be more encouraged to experiment with methods informed by mindfulness and meditation, but also other contemplative-based practices and frameworks. [55]

In addition, ample possibilities exist for researchers to utilize mindful coding within their data collection and analysis. For instance, bringing qualities of openness and non-judgment, in itself, could add a new dimension to field notes, interviewing, and thematic coding (MILLER, 2016). Furthermore, as Steve has tried, researchers who have existing meditation practice—or start one—might further experiment with and document their experiences with focusing on data and bringing it to more subtle, quieter states. For example, do other researchers experience "theme jumping" or other non-traditional ways of moving from coded data to more fully formed themes or findings? [56]

Additional research might be conducted on how engaging in mindfulness and meditation-based approaches impact researchers' relationships with participants and impact researcher's ethical views, their ability to form bonds, deeply understand the perspectives of those they research with, and create an ideal position to do no harm. Furthermore, based on our findings, we believe researchers can experiment with practices that foster creative silence as a condition for generating insights and findings within qualitative methodological processes. In the end, our inquiry yielded the insight that a meditative or mindful awareness, encouraged by contemplative and mindful inquiry frameworks, can be a powerful tool for qualitative researchers, allowing them to relax into their work, become more conscious of experiences around them, and the interconnectedness that exists with all. [57]

1) One name censored in Line 10 to protect identity. <back>

2) The Four Noble Truths are foundational teachings in Buddhism: 1. Life involves suffering, 2. suffering is caused by craving and attachment, 3. the cessation of suffering is possible, and 4. there is a path (the Eightfold Path) that leads to the end of suffering. <back>

Agar, Michael (1994). Language shock: Understanding the culture of conversation. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Agar, Michael (2004). We have met the other and we're all nonlinear: Ethnography as a nonlinear dynamic system. Complexity, 10(2), 16-24, https://doi.org/10.1002/cplx.20054 [Accessed: July 7, 2025].

Agar, Michael (2006a). Culture: Can you take it anywhere?. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2), 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500201 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Agar, Michael (2006b). An ethnography by any other name. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 36, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.4.177 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Barbezat, Daniel P. & Bush, Mirabai (2013). Contemplative practices in higher education: Powerful methods to transform teaching and learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bentz, Victor M. & Shapiro, Jeremy J. (1998). Mindful inquiry in social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bhattacharya, Kakali & Cochrane, Meaghan (2017). Assessing the authentic knower through contemplative arts-based pedagogies in qualitative inquiry. Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 4(1), Art. 3, https://digscholarship.unco.edu/joci/vol4/iss1/3 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Bodhi, B. (Trans.) (2000). The connected discourses of the Buddha: A translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Baltimore, MD: Wisdom Publications.

Breuer, Franz (2000). The "other" speaks up. When social science (re)presentations provoke reactance from the field. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art. 28, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1122 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Brown, Candy G. (2017). Ethics, transparency, and diversity in mindfulness programs. In Lynette M. Monteiro, Jane F. Compson & Frank Musten (Eds.), Practitioner's guide to ethics and mindfulness-based interventions (pp.45-85). Cham: Springer.

Burrows, Linda (2017). Safeguarding mindfulness in schools and higher education: A holistic and inclusive approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

CohenMiller, Anna & Boivin, Nettie (2021). Questions in qualitative social justice research in multicultural contexts. New York, NY: Routledge.

Creswell, John W. & Poth, Cheryl (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Delamont, Sara (2008). For the lust of knowing—Observation in educational ethnography. In Geoffrey Walford (Ed.), How to do educational ethnography (pp.39-56). London: The Tuffnell Press.

Emerson, Robert M.; Fretz, Rachel I. & Shaw, Linda L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

González-López, Gloria (2011). Mindful ethics: Comments on informant-centered practices in sociological research. Qualitative Sociology, 34(3), 447-461.

Haberlin, Steven (2019). Supervision in every breath: Enacting Zen in an elementary education teacher program. Doctoral dissertation, teacher education, University of South Florida, FL, USA. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/7801/ [Accessed: July 21, 2025].

Hammersley, Martyn & Atkinson, Paul (2019). Ethnography: Principles in practice (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hein, Sarah F. & Austin, Wendy J. (2001). Empirical and hermeneutic approaches to phenomenological research in psychology: A comparison. Psychological Methods, 6(1), 3-17.

Heron, John (1996). Co-operative inquiry: Research into the human condition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hyland, Terry (2017). McDonaldizing spirituality: Mindfulness, education, and consumerism. Journal of Transformative Education, 15(4), 334-356.

Jacobs, Gabriel (2003). The ancestral mind: A revolutionary, scientifically validated program for reactivating the deepest part of the mind. New York, NY: Viking.

Janesick, Valerie J. (2015). "Stretching" exercises for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Janesick, Valerie J. (2016). Contemplative qualitative inquiry: Practicing the Zen of research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Janesick, Valerie J. (2022). Contemplative qualitative inquiry: Practicing the Zen of research—virtual workshop. Workshop, September 23, The Qualitative Report, online, https://tqr.nova.edu/valerie-j-janesick-contemplative-qualitative-inquiry-practicing-the-zen-of-research/ [Accessed: July 21, 2025].

Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2001). Mindfulness meditation for everyday life. London: Piatkus Books.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2013). Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Konecki, Kryzsztof T. (2019). Creative thinking in qualitative research and analysis. Qualitative Sociology Review, 15(3), 6-25, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.15.3.01 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Konecki, Kryzsztof T. (2021). The meaning of contemplation for social qualitative research: Applications and examples. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lincoln, Yvonna S. & Guba, Egon G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mason, Oliver J. (2002). The application of mindfulness meditation in mental health: Can protocol analysis help triangulate a grounded theory approach?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), Art. 23, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-3.1.885 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Maté, Gabor (2011). When the body says no: Exploring the stress-disease connection. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

Mazzocchi, Fulvio (2020). A deeper meaning of sustainability: Insights from indigenous knowledge. The Anthropocene Review, 7(1), 77-93.

McDonald, Kelsang (2005). How to meditate: A practical guide. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Mehta, Niyati N. & Talwar, Gurmeet (2022). Recognizing roots and not just leaves: The use of integrative mindfulness in education, research, and practice. Psychology from the Margins, 4(1), Art. 6, https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/psychologyfromthemargins/vol4/iss1/6/ [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Mertens, Donna M. (2007). Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 212-225, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807302811 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Miller, John P. (2016). The embodied researcher: Meditation's role in spirituality research. In Jing Lin, Rebecca L. Oxford & Tom E. Culham (Eds.), Toward a spiritual research paradigm: Exploring new ways of knowing, researching and being (transforming education for the future) (pp.127-140). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Napora, Laura (2017). A contemplative look at social change: Awareness and community as foundations for leading. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 4(1), 188-206, https://digscholarship.unco.edu/joci/vol4/iss1/10/ [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Neale, Miles (2017). Buddhist origins of mindfulness meditation. In Joseph Loizzo, Miles Neale & Emily J. Wolf (Eds.), Advances in contemplative psychotherapy: Accelerating healing and transformation (pp.36-57). New York, NY: Routledge.

Nguyen, Megan (2018). The creative and rigorous use of art in health care research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Art. 19, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2844 [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Orellana, Marjorie E.F. (2020). Mindful ethnography: Mind, heart and activity for transformative social research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Patton, Michael Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Purser, Ronald (2019). McMindfulness: How mindfulness became the new capitalist spirituality. New York, NY: Repeater/Random House.

Rawls, John (2005 [1971]). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Reason, Peter & Rowan, John (Eds.) (1981). Human inquiry: A sourcebook of new paradigm research. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Romero, Steven M. (2016). The awakened heart of the mindful teacher: A contemplative exploration. Dissertation, teacher education, University of Pittsburgh, PA, US, http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/30543/ [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Rosenthal, Norman E. (2017). Super mind: How to boost performance and live a richer and happier life through transcendental meditation. New York, NY: Penguin.

Roth, Harold D. (2014). A pedagogy for the new field of contemplative studies. In Olen Gunnlaugson, Edward W. Sarath, Charles Scott & Heesoon Bai (Eds.), Contemplative learning and inquiry across disciplines (pp.97-118). Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Smith, Linda Tuihiwai (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Spittler, Gerd (2001). Teilnehmende Beobachtung als dichte Teilnahme. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 126(1), 1-25.

Spradley, James P. (2016 [1980]). Participant observation. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Street, Brian V. (1993). Culture is a verb. In David Graddol, Linda Thompson & Michael Byram (Eds.), Language and culture (pp.23-43). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters/BAAL.

Topolinski, Sebastian & Reber, Rolf (2010). Gaining insight into the "Aha" experience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(6), 402-405.

Van Manen, Max (2017). But is it phenomenology?. Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 775-779.

Wang, Hongyu (2022). Daoist creativity through interconnectedness and relational dynamics in pedagogy. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 29(3), 183-196, https://doi.org/10.7202/1094135ar [Accessed: July 15, 2025].

Watts, Joanna H. (2009). From professional to PhD student: Challenges of status transition. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(6), 687-691.

Zajonc, Arthur (2008). Meditation as contemplative inquiry: When knowing becomes love. Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne Books.

Zajonc, Arthur (2016). Contemplation in education. In Kathleen A. Schonert-Reich & Robert W. Roeser (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness in education: Integrating theory and research into practice (pp.17-28). New York, NY: Springer.

Megan MITCHELL is an assistant professor of research methods in the Department of Leadership, Technology, and Workforce Development at Valdosta State University in Georgia, USA. In her research, she focuses on interactional ethnography, teaching and learning qualitative research, and arts-based methods and pedagogies. She teaches and advises doctoral students in qualitative research.

Contact:

Megan Mitchell

Department of Leadership, Technology, & Workforce Development

Valdosta State University

1500 N Patterson St

Valdosta, GA 31698, USA

E-mail: megmitchell@valdosta.edu

Steve HABERLIN is an assistant professor in the College of Community Innovation and Education at the University of Central Florida, USA. In his research, he explores meditation and other mind-body practices in higher education. He has also taught in K-12 settings and incorporates mindfulness-based approaches into both teaching and research.

Contact:

Steve Haberlin

Department of Learning Sciences and Educational Research

College of Community Innovation and Education

University of Central Florida

12494 University Blvd.

Orlando, FL 32816, USA

E-mail: steve.haberlin@ucf.edu

Mitchell, Megan K. & Haberlin, Steve (2025). Experiencing interconnectedness through mindful inquiry and meditative thematic analysis in social science research [57 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 26(3), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-26.3.4407.