Volume 6, No. 1, Art. 23 – January 2005

Emergence of Meanings Through Ambivalence

Emily Abbey & Jaan Valsiner

Abstract: Ambivalence has been a key notion that is used in most basic areas of psychology—research on perception, thinking, personality, and communication. However, its implications for processes of meaning-making have been largely overlooked. All meanings are created in the present (integrating elements of past experience) in relation to a future that can never be entirely determined at the present. We outline a developmental model of how meaning emerges through the tensions between the present and the future. Three trajectories can be found in this process. First, lack of ambivalence (the null condition) leads the meaning production to reach a status quo and decline. Secondly, low to moderate ambivalence leads to erratic movement of starting and stopping of the meaning making through the production signs. These signs tentatively control meaning in the present while not constraining the path meaning may take in the future. Thirdly, maximum ambivalence leads to the emergence of "strong" signs that function to constrain the uncertainty of the future as it is becoming present. Empirical data from a microgenetic study of meaning making in the development of young adults will be used to illustrate the model.

Keywords: ambivalence, uncertainty, microgenesis, semiotic mediation, ambiguity, pre-control, attractor point, semiotic emergence, projective contextualization

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

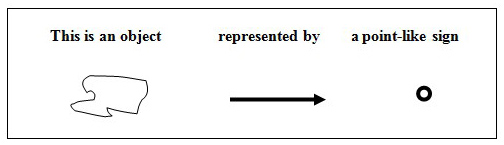

2. Human Development: Relating With the World Through Signs

2.1 Two directions in conceptualizing semiotic mediation

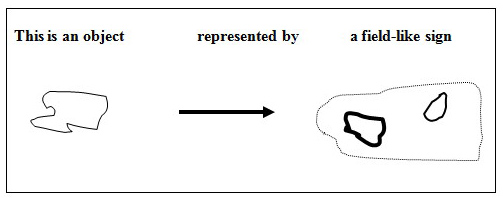

2.2 Representing versus presenting

2.3 A theoretical system recognizing the unity of point-like and field-like signs

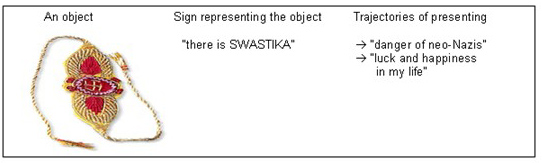

3. The Centrality of Ambivalence in the Meaning Making Process

3.1 Functional ambivalence and the emergence of signs

3.1.1 The null condition—no sign

3.1.2 Erratic meaning making through fragile and medium signs

3.1.3 Bifurcation of trajectories: Construction of strong sign versus loss of sign all together

3.2 How are developing persons "being helped" by "social others"?

3.3 Psychological distancing and projective contextualization

4. Examples

4.1 The study

4.2 Results

5. Discussion

All development is necessarily based on uncertainty—between what has already developed and what could develop in the next time moment. As such, development requires an orientation toward the present that runs contrary to our usual conceptions. In case of the latter—we have little difficulty understanding that the present has been influenced by the past, but we don't often consider that the present is affected by the future. In fact the very idea that the future might play a role in the present may seem counterintuitive, at the first glance. We usually tend to think of the present and the future as isolated from one another. [1]

However, that commonsense idea of isolation of what already exists (past and present) and what might exist (future) obscures the possibilities for scientific inquiry of development. Even in case of physical systems—such as ocean waves that fluctuate in a nonlinear way—the emergence of the next wave depends upon both the previous ones, and on a future "attractor point" as the Dynamic Systems Theory suggests (VALSINER, 2002). The immediate link of the past and present with the making of the future is even more profound in the biological world. [2]

The experiencing organism—of any species—necessarily needs to be oriented towards the immediate future. This takes the form of qualitative transformation of dynamic structures. One's basic biological survival depends on not being captured by the predators in the next—not yet actualized—moment. Turning to the species that is the biggest predator to all others—Homo sapiens—the anticipatory integration of the future in the past-to-present entails the use of higher mental functions to plan for the next moment's experiences. Human beings do not merely anticipate what might happen with them—they make something new happen through their actions. Hence the future is very much a part of the present—as any anticipation of the future is not itself in that future, but in the move towards it. [3]

Future's "influence" upon the present has an interesting quality—the future can never be known before it becomes present. It can only be estimated within a given set of possibilities. It can be imagined—in ways that combine affective and rational sides of such estimation. The possibilities of what could happen "in the future" are many—a field, or a range—yet out of those only one will be actualized. How is that transformation from uncertainty of many possibilities (the expected future) to the actualized certainty happening? In the human case, we need to examine the role of semiotic mediation as the functional mechanism of that transformation. Yet understanding transformation also requires methods that are focused on process rather than outcome. Not all qualitative methods are well suited to looking at process. In fact, the fit of qualitative or quantitative methods always requires an analysis of the methodological cycle as a whole (BRANCO & VALSINER, 1997). [4]

2. Human Development: Relating With the World Through Signs

In the process of human development—both microgenetic and ontogenetic—new meanings are constructed through the emergence of signs to help the individual in the awkward dance of adapting to the present—while dealing with various possibilities (uncertainty) of the future. The person is constantly operating at the boundary of time—moving from what is (at this moment) the miniscule present towards the not-yet-determined moment of future. That movement determines the new present (former future), setting the base for the next uncertainty of the future, which is then overcome, and so on—ad infinitum. [5]

Development can be characterized in terms of infinite sets (MATTE BLANCO, 1975, 1988) where the past is the known (at present) realization of the boundary of the set, while each new member of the set (experience) is unknown. The infiniteness of development does not necessarily end at the time of the demise of a person—as human societies have created elaborate belief systems that treat the state of human physical death as a move towards another infinite future (beliefs in afterlife, in cyclicity of re-birth, etc.). The dying person's beliefs in the expected future may dramatically re-organize the person's handling of movement into death—as the executioners of the early Christians during the end of the Roman Empire were surprised to find out. [6]

2.1 Two directions in conceptualizing semiotic mediation

If a theoretical focus is set upon the centrality of signs (semiotic mediation), signs stand in for something else—objects, other signs, etc. As such, they can be conceptualized as objects without spatial and temporal extension—a point representing an object:

Illustration 1: Point-like sign [7]

Many signs are point-like. A word—"a bird"—despite its various nuances of sense, ranging from anatomical referencing to poetic overgeneralization—is still represented in our speaking or writing by the same form "bird" in a point-like fashion. [8]

An alternative to the point-like depiction of signs is a field description. In this case we get a different picture:

Illustration 2: Field-like sign [9]

Here the concreteness of the object becomes organized into a sign field that is internally structured (including "anchor domains" within widely open boundaries of the meaning involved). Thus, a real-life event (e.g., a young girl going to a public area and exploding a bomb attached to her body) may become represented by the general field of TRAGIC HAPPENING within which two opposing "anchor domains"—sub-fields of HEROISM or TERRORISM may relate to one another to capture the meaning of the event—for others, of course, and after the potential for the suicide bombing has become the actual past of the act. It is not difficult to see how point-like signs are a special case of field-like signs (namely—the point is the infinitely diminished field). Hence the two depictions are not irreconcilable opposites, but mutually inclusive. [10]

2.2 Representing versus presenting

Semiotic mediation would not help us much for making sense of development if it stopped merely at signs representing something else. The actual ways in which signs function need to be studied. Human beings create and use meanings not merely for the sake of commenting upon the world as it is, but in an effort to actively relate to it—be prepared for what is to happen, or make it happen. In each representation by a sign is a presentation—a suggestion for the immediate (and not so immediate) future. Thus, the picture becomes explicitly future-oriented (see Illustration 3). The specific rakhi depicted as object on the left is something that is a luck-bringing charm for one's brother in a Hindu family context, including the auspicious sign of a right-handed swastik. Recognition of the representation of the symbol can be shared by various interpreters—while its presentational implications vary dramatically based on the cultural historical happenings in the European versus Hindu worlds.

Illustration 3: Differential presentation by a representing sign [11]

As one can see, while the OBJECT → SIGN representational road may be similar, the implications of the representation—presentation for the future—are cardinally different given a person's cultural history (European or Indian). The presentational focus of a sign builds the bridge from the past → present to the sense for possible future. [12]

2.3 A theoretical system recognizing the unity of point-like and field-like signs

The interesting relation of the present to the future that we speak of can be described in abstract terms A and Non-A, where any mention of A (the present time) necessarily also refers to its opposite field—designated as Non-A:

Illustration 4: A & Non-A fields [13]

Non-A is the field that consists of all the possible transformations that A—in the present—is not—but what it could become in the future (JOSEPHS, VALSINER & SURGAN, 1999). In the process of actualizing the future from within a set of possibilities, the person operates within various ambivalences between A and Non-A or in other words, ambivalence because the certain or uncertain present relation of the person and the environment is in tension with the future uncertain expectation of the next encounter with the world. It becomes clear that all development is inherently based on overcoming uncertainty through the means of relatively uncertain kind (such as signs). Every new contextualization of a sign evokes some kind of discrepancy of the presentational kind—a state of ambivalence. [14]

3. The Centrality of Ambivalence in the Meaning Making Process

We define ambivalence as a tension produced by a system entailing a kernel and at least two vectors that are non-isomorphic in size and direction. In such a system, ambivalence can occur under all situations except one, where the vectors are of exactly the same size and direction (Option D; see Illustration 5, below). Option A represents the most typical understanding of ambivalence—two equally strong forces pulling the individual in opposite directions. In our current application this represents the maximum degree of ambivalence between the present and the future. Options B and C produce ambivalence that is weaker, yet nonetheless present. In option B, although the two forces are not completely opposing, they create a tension between two different orientations. In option C it is the discrepancy in strength of forces that creates ambivalence.

Illustration 5: Different forms of ambivalence [15]

Our notion of ambivalence created by vectors of different size and direction borrows from topological psychology (LEWIN, 1936) that suggests a life space filled with forces of different degrees of attraction or repulsion. We might conclude that an ambivalent life space is one in which the individual experiences forces that pull him or her in different directions, not only in terms of material objects (such as toward the cookies or the celery) but also in terms of trying to prepare for the present and the future simultaneously. LEWIN showed how humans, in the present, maintain a psychological awareness for what they desire in the future. In our current focus, the desire can be thought of as no more than the want to know what is coming, the desire for certainty. [16]

3.1 Functional ambivalence and the emergence of signs

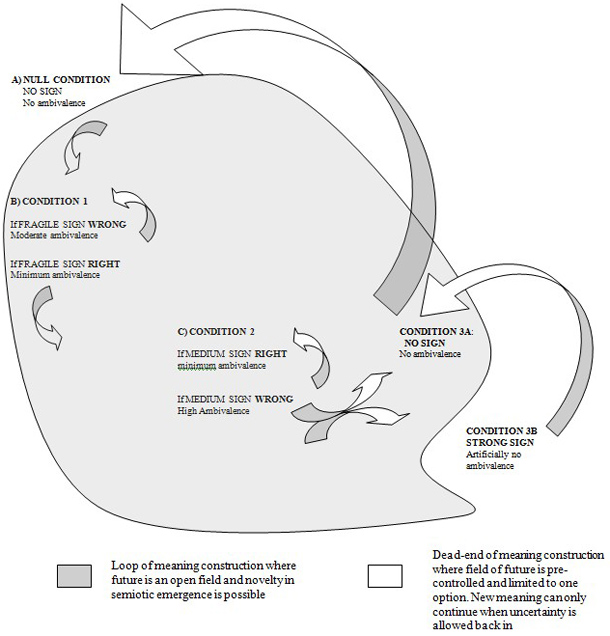

All signs contain an element of certainty—the part of the meaning that "feels right" at the present—which is quickly taking a form expected from the future. Since the time period of the present is infinitely small (between past and future—see PEIRCE 1935, p.104) there is practically no opportunity for the meaning-making person to adequately evaluate the "rightness" (or "wrongness") of the meaning-in-construction. The process of semiotic emergence is driven by the ambivalence between these two elements, between what one got right, and what one got wrong (but now knows) that will in turn be part of the next emerging meaning. As such, increasing and decreasing levels of ambivalence construct a self-perpetuating process of meaning construction and emergence of signs with a number of different conditions as explained in detail below (see Illustrations 6,7, and 8 below).

|

NULL CONDTION: No sign – No ambivalence |

|

I really don't know what it is and I don't want to know [no sign] → (no ambivalence) |

|

MOVE TO CONDITION 1 WHEN AND IF WANT TO KNOW OCCURS |

|

CONDTION 1: Fragile sign - Moderate ambivalence or Minimum ambivalence |

|

I really don't know what it is [certainty 10% uncertainty 90%] but I want to know [fragile sign] → I was almost completely wrong [certainty 10% uncertainty 90%] (moderate ambivalence) → fragile sign remains fragile. STAY IN CONDITION 1 |

|

OR |

|

I really don't know what it is [certainty 10% uncertainty 90%] but I want to know [fragile sign] → I was almost completely right [certainty 90% and uncertainty 10%] (minimum ambivalence) → Fragile sign becomes medium sign. GO TO CONDITION 2 |

|

CONDITION 2: Medium sign – Minimum ambivalence or Maximum ambivalence |

|

I think I know what it is [certainty 50% uncertainty 50%] and I want to know [medium sign] → I was almost completely right [certainty 90% uncertainty 10%] (minimum ambivalence) → medium sign remains medium sign. STAY IN CONDITION 2 |

|

OR |

|

I think I know what it is [certainty 50% uncertainty 50%] and I want to know [medium sign] → I was almost completely wrong [certainty 10% and uncertainty 90%] (maximum ambivalence) → medium sign becomes strong sign. GO TO CONDITION 3A or 3B |

|

CONDITION 3A or 3B: Strong sign-Artificially minimum ambivalence or No Sign-No ambivalence |

|

3A I don't know anything at all [no sign] → no ambivalence return to NULL CONDITION |

|

OR |

|

3B I know [strong sign] → artificial minimum ambivalence STAY IN CONDITION 3 OPTION 3A OR 3B FOLLOWS UNTIL UNCERTANITY IS ALLOWED TO RE-ENTER → THEN GO TO CONDITION 2. |

Illustration 6: Ambivalence in semiotic mediation [17]

Illustration 7: Dynamics of ambivalence [18]

|

|

I don't know what it is and I don't want to know (focused on other things) |

|

Null Condition |

|

|

Okay, now I still don't know what it is, but I want to know → |

|

Move to Condition 1 |

|

fragile sign [" It seems suspicious, but I am not sure"] → hmmm, well I am almost completely wrong, that makes me frustrated because I want to know but don't (moderate ambivalence) but I'll try again |

|

Stay in Condition 1 |

|

|

Okay, now I still don't know what it is, but I want to know → fragile sign ["It seems sexy, but I am not sure"] → I am almost completely right → great, I like knowing what is going on (minimal ambivalence) |

|

Move to Condition 2 |

|

|

Okay, I think I know what it is → medium sign [It seems sexy, maybe it is a woman] → I am almost completely right → that's really good (minimal ambivalence) |

|

Stay in Condition 2 |

|

|

Okay I think I know what it is → medium sign [It seems sexy, maybe it is a woman, maybe is a mother breastfeeding] → I must be wrong! Breast-feeding is not sexy! I am crazy to think that! Oh no, that is REALLY FRUSTRATING, I thought I knew what is was AND NOW I DON'T! (maximum ambivalence) |

|

Move to Condition 3B |

|

|

Okay, I know what it is → strong sign [breast-feeding in public is wrong] |

|

Stay in condition 3B until uncertainty is allowed to enter again |

|

|

Okay, I know what it is → strong sign [breast-feeding in public is wrong] |

|

Stay in condition 3B until uncertainty is allowed to enter again |

Illustration 8: An example of the dynamics [19]

We here are describing the emergence of the minimal version of the hierarchical system of semiotic mediation from the flow of personal experience (see VALSINER, 2001a for elaboration on the hierarchies of semiotic mediation). Yet there are a number of ways in which meaning can be generated, based on this model. [20]

3.1.1 The null condition—no sign

In the null condition, there is no tension between certainty and uncertainty, usually because the person does not know what something is, and does not care to find out. In the next moment, the individual may somehow become attracted to caring and the ambivalence may begin to develop, or the thing may pass into the abyss of the many things we encounter and do not focus on. [21]

3.1.2 Erratic meaning making through fragile and medium signs

In the states of minimum to moderate ambivalence—"I don't know what it is, but I want toàI am wrong" to "I don't know what it is, but I want toàI am right"—the process of meaning making becomes erratic. The person may continue for long time between the reflections—"I know what it is ... I don't know what it is ... ." This erratic striving towards meaning—based on the opposition created by the person—is the basis for further transformation. The meaning seeking process may become extinguished—if it moves back into the null condition of back to no ambivalence ("I don't know what it is and don't care"—cf. JOSEPHS & VALSINER, 1998, on circumvention strategies). Or, alternatively, it may escalate into maximum ambivalence. [22]

This kind of meaning making serves the purpose of pre-adaptation most successfully, for it does not overly restrict the openness of the field of the future, yet it guides the individual in a possible direction. The erratic striving towards meaning can be likened to the basic developmental mechanism of "trying—and trying again"—or persistent exploration of the realm of possibilities of the moment. It is out of such explored forms that further construction of meaning may ensue. [23]

3.1.3 Bifurcation of trajectories: Construction of strong sign versus loss of sign all together

When ambivalence reaches its maximum level, two opposite events may happen in relation to the emerging sign. In Condition 3A the sign disappears from the context all together as ambivalence is reduced by over-emphasizing uncertainty ("I don't know anything"). Here the individual may return to earlier stages and try again, thinking of new meanings, or the process may die out completely. [24]

In contrast, Condition 3B is most likely to lead to momentarily stable signs that mediate uncertainty by pre-controlling the meaning of a situation. Although more poorly suited to helping the individual pre-adapt to the indeterminate future if it narrows the field of possible meaning too much (an extreme that is usually unavoidable), it provides the clearest path for the individual to follow and is the best way that an individual can function at the given moment. In situations when the cost of uncertainty is perceived as highly detrimental and some action must be taken, such momentary monologization of the otherwise dialogical meaning construction process frequently occurs. [25]

Pre-control of uncertainty in the future is accomplished by an intensification of one aspect of the previous sign's meaning field. Frequently (but not always) this occurs by ignoring the aspects of the sign that seem most uncertain, and specifying the meaning constructed. Thus, "suspicious" becomes "yes, it is a THIEF." In this way, Condition 3B produces a strong sign by over-determining the field of possible futures until it no longer represents an open set, but rather is limited to one specified meaning (a "B" emerging from the field of "Non-A" using the terminology of Illustration 4). Thus, a general—point-like—sign emerges at the level of personal meaning, taking over the regulatory function from the quasi-differentiated field of personal experiencing:

Illustration 9: Before and after sign emergence [26]

3.2 How are developing persons "being helped" by "social others"?

It is not surprising that the crossroads—the bifurcation point—between Condition 3A and Condition 3B are also the loci for purposeful semiotic intervention by the person's "social others"—friends, family, social institutions, or any social organism the goal of whom is to "capture" the individual to enter into some form of communion with them. The intervention agents may belong to different historical times and places—the Cattedrale di Milano (built and re-built over five hundred years—from 1386 to 1887) would suggest to us a serene and subdued attitude towards our internal meaning-making turmoils. The signs can be simply encoded in the environment, "left behind" by their makers—yet still functional for the meaning construction process.1) [27]

Thus, all interventions entail two things: the provision of strong signs and the corresponding suggestion that these signs, rather than the personally emerging ones, be used in meaning-making. It is at the moments—such as the move from a medium sign to the bifurcation of Conditions 3A and 3B (Illustration 8)—that the meaning-making system makes itself open to interventions. Such acts of intervention—usually presented as "help" from the side of goal-oriented and self-interested intervener—can work precisely under conditions of this increased need to overcome intolerably escalated uncertainty. Their "working" is no credit to the intervener alone—the success of intervention is finally determined by the system that is being intervened. The person who is "being helped" lets that "help" have its role only through the co-construction process led by the person. [28]

The person—the target of such interventions—makes the intervention efforts either functional (by accepting the insertion of the suggested meaning, and letting it organize the meaning-making process further), or functionless through rejecting such efforts. The latter—rejection—is the usual state of affairs where the overwhelming majority of social suggestions that target the person go unnoticed, ignored, or brushed aside. Hence—on the side of the interveners—there is a need to pre-emptively compensate for the power of rejection of the messages by their targets—through over-determination by meaning. High redundancy of similar messages are made to surround the target—so any social intervention system works "wastefully," with overproduction of social suggestions. This "wastefulness" is inevitable given the primacy of blocking the majority of social suggestions. [29]

3.3 Psychological distancing and projective contextualization

There are at least two general qualities of importance in human perception relevant to the process of semiotic emergence modeled here. First and foremost—the perceiving person is in a Subject-Object relation with the perceivable world. The primary condition of the perceiving act is the distancing of the Subject (perceiver) from the Object (perceived)—act of objectification2). Based on that primary distancing, the perceiver can begin to make sense of the sensory properties of the objects. [30]

The making sense of the environment is both perceptual and meaning-constructive. Not only can the direct physical properties of an object within an environment create phenomenological properties within the perceiver—subjective size, shape, color, etc. but these become part of the meaning making process of what these objects are (e.g., "It is round and blue, it might be a lake"). The emotional and aesthetic qualities that we experience ("The lake seems serene and peaceful") constitute additional layers of meaning. The primacy of the aesthetic appreciation of the world has been designated as the highest level of the development of human persona (BALDWIN, 1915; VYGOTSKY, 1971). Thus, the making of the aesthetic meaning of the living experience is part and parcel of the relating with the world. [31]

Aesthetic philosophy suggests that the act of distancing is an important means by which we can gain access to this later layer of human perception (BULLOGH, 1912; CUPCHIK & WINSTON, 1996). Similarly, the process of distancing is indicated for ontogeny (SIGEL, 2002). In distancing, the individual psychologically moves away from the object of perception, such that the object becomes distinct from the self. This metaphysical separation—in the form of inclusive separation (VALSINER, 1997, p.24)—allows for reflection and the formation of new intimate relations with the object, wherein the object becomes imbued with deeply personal meanings not present in non-distanced contemplations. [32]

Distancing is thus central for human psychological functioning—by creating the contrast between the participation in the here-and-now context (activity setting) and one's subjective world of there-and-now, or there-and-then, ideations. The latter maintain previously constructed signs in forms that allow the person to re-insert them into their meaning-making process under new circumstances. Generalization of signs—through the person's psychological distancing—allows for their re-contextualization when needed (VALSINER, 2001a). [33]

Projective contextualization is the process of such re-insertion of previously assembled meanings into the process of emergence of the personal sense under new circumstances. For example, seeing a photograph of a woman's breasts the individual might construct the fragile sign ("Those are beautiful breasts, but seeing naked breasts is strange"). Here we see two meanings projectively contextualized, for neither "strange" nor "beautiful" are in the image—the image only contains breasts. It is the individual, projecting internalized general social knowledge about the meaning of naked breasts that creates the "strangeness" and "beauty." [34]

Projective contextualization exists in two forms—personal and social. Personal projective contextualizations prioritize the ideas of the individual over those of the social (moral values, social norms etc.) Social projective contextualization are the opposite, emphasizing social values over the ideas of the individual. Personal projective contextualization is the kind most frequently present at Condition 2, such as in the example above. When two personal projections cannot be integrated at Condition 2 ("These breasts are beautiful but they are also strange, so what do I feel?") this triggers the escalation into Condition 3. This is the point where social projective contextualizations such as ["Naked breasts are pornographic"] may be inserted over personal contextualizations. When this occurs, a strong sign is formed ("I see beautiful breasts, but it is strangeàI am looking at PORNOGRAPHY"). As described above, the social intervention overrides the emerging meaning, guided by personal projective contextualization. The person is "helping" oneself to make meaning, and reducing ambivalence—by projecting a sign into the relationship with the world. The projected sign may end up dominating ("This is not beautiful because it is pornographic"), or may be rejected ("Many say this is pornographic, but they are wrong—it is beautiful"). Other developments may include the "feed-in" of one of the meanings into the other ("if they say that this is pornographic—then pornography is beautiful"). The latter overcomes the ambivalence in the meaning construction process (as would other hybrids: "this is beautifully pornographic" or "pornographically beautiful"). [35]

In contrast, the meaning of personal projective contextualization can also be integrated, and when thus occurs, there is no movement into Condition 3 as the ambivalence never grows strong enough. Many integrations require circumvention (JOSEPHS & VALSINER, 1998) where the individual imposes a personal organization of some sort upon social meanings to reduce the tension that might otherwise exist between them. Thus, projective contextualization serve a dual role: 1) they set the stage for possible escalation of ambivalence by introducing uncertainty, 2) they either force the construction of a strong sign if there is no integration (move to Condition 3), or maintain the current level of ambivalence (stay in Condition 2) if there is integration of meaning. [36]

We will now outline the proposed model of semiotic emergence driven by the ambivalence between certainty and uncertainty using empirical data from a microgenetic study of meaning making in the lives of young adults. It is important to point out that developmentally oriented (then called genetic) research that was begun by the different directions within the Continental European psychology of the beginning of the 20th century has lost its popularity in the last five decades, necessitating efforts to give it a new birth under the appealing label "developmental science" (e.g., CAIRNS, COSTELLO & ELDER, 1996). Yet our contemporary developmental science does not penetrate our research methodologies. Thus, the classic methodologies of the study of emergence in time—very natural within the traditions of Ganzheitspsychologie (see DIRIWÄCHTER, 2003) or in the early work of Jean PIAGET (VALSINER, 2001b)—are only slowly re-entering the research arena of developmental psychology (cf. SIEGLER, 1996). [37]

Our empirical examples come from a set of experiments that used the microgenetic method. That method was made popular in the English language psychological literature by Heinz WERNER in the early 1950s (e.g., WERNER, 1956). The method entails the investigation of the progression of one form of a given phenomenon into another. The forms themselves are but boundary states for the study of the transformation process. For example, while a non-developmental study would explore the transition of forms AàBàC as simple occurrence of separate forms (A,B,C), a microgenetic study is concerned with the progression from A-B and B-C, focusing on forms that can be observed at the transition moments (e.g. AàabàB, and BàbcàC, where the ab and bc are intermediate, transitory forms). [38]

Of course this research strategy is shared by all levels of developmental analysis—phylogenetic, cultural-historical, ontogenetic, and microgenetic (GOTTLIEB, 1999) Here we take the micro level phenomenon—an adult's gradual making of the meaning of an decreasingly fuzzy picture—and study it from the angle of the emerging intermediate forms of what is perceived, and the construction of affect-laden meanings of the gradually disambiguated form. [39]

Undergraduate and graduate student participants from a small university (7 male and 23 female took part in this study). Participants were seated across from the experimenter and asked to view a series of images that the experimenter held (see figures below). The series was composed of a single image that had been made blurry using a computer (see Illustration 10, Images 1 and 2). In the experimental setting, the initial image had the highest level of blurriness, while the last image (Illustration 10, Image 4) was a completely unmodified version of the original image. The intermediate two images decreased in degree of blurriness.

Illustration 10: Stimuli used in the experiment [40]

While viewing each image, participants were asked to verbally communicate what they were thinking as they tried to make sense out of the image, and then to rate the image according to a series of descriptors:

Illustration 11: Scale used in study [41]

As will be visible below, participants continued their elaboration of the images through the use of meanings communicated to them via the end points of the bipolar scales. Thus the scales—researchers' instrument—entered into the meaning-making process as tools for understanding. Consistent with the ethos of the microgenetic methodology, it was the process of use of the opposites of the scales that constituted our data, rather than the marks persons made on the scales3). [42]

Participants used all the different ways to construct meaning described by our general model. The most frequent forms of meaning construction for the participants fall under Conditions 1 & 2. Not only were these the most frequent, they were used by all participants. Conditions 1 & 2 are best equipped to make sense of the present while not restricting the field of the future, and therefore it seems logical they used this form so frequently in a setting where they were profoundly aware (due to the blurriness of the images) that they do not know what was coming. [43]

The first example given in depth consideration with respect to our model comes from a 21 year-old woman. She is shown the first image in the series and responds with the comment below:

Illustration 12: First response participant A [44]

In this example a fragile sign emerges ("abstract painting") although the participant clearly marks that the blurriness of the image prohibits her from feeling like she has come to the right conclusion. Her ambivalence is at a moderate level in that she wants to know but currently does not. The participant is shown the next image and she responds in the same manner as before, still in Condition 1 of semiotic emergence:

Illustration 13: Second response participant A [45]

It is interesting to notice, as this example points out, that there may be any given number of cycles within a condition. Within Condition 1, as the cycle repeats the same fragile sign may be constructed (as in this example), however, another equally fragile sign could also emerge (e.g., "it looks like a sunset, but I am not sure"). In either case, the important point is that the meaning of the sign does not completely determine the situation. [46]

As the participant is shown the third image, the process of semiotic emergence begins to accelerate. Here the fragile sign is transformed into a medium sign ("definitely breasts"). Then following the construction of this medium sign, Condition 2 repeats itself, but something goes wrong as the participant perceives an aspect that does not (for her) mesh with "breasts" (a "see-through" shirt). The participant moves into Condition 3B, pre-controlling uncertainty of the field of possible futures by constructing the strong sign ("hooker"). Here is a clear example of how Condition 3B artificially narrows the field of possible meaning for the future down to one option, in this case "hooker."

Illustration 14: Third response participant A [47]

Finally, in Image 4 we see the continuation of Condition 3B with the use of the sign ("hooker") to describe the image. We can see how meaning production has been stalled by the creation of a strong sign which must, by definition, shut out all other sources of uncertainty, thereby stagnating the meaning constructive process as there cannot be any change until some uncertainty is allowed to reenter.

Illustration 15: Fourth response participant A [48]

A second participant shows variation within this general model. This participant is a woman, also 21 years old. Her comments about the first two images are the most interesting, for they show the movement from null condition into Condition 1. While viewing the first image she says:

Illustration 16: First response participant B [49]

This example emphasizes the gradational nature of the meaning constructive process, where signs exist and fade much like a shadow on a partly sunny day, becoming strong in clear sky and gradually weaker as a cloud passes, only to resurge when the cloud disappears. In viewing Image 2 the participant remains in Condition 1, continuing to try to figure out what she sees:

Illustration 17: Second response participant B [50]

It is not until the third image that the participant moves from Condition 1 (colors) into Condition 2. Presumably, according to our model, before moving to Condition 2 the participant went through an additional round of Condition 1, however the unfortunate aspect of studying perceptual processes is that they happen with rapid speed and even through a microgenetic setting it is hard to capture everything that goes on:

Illustration 18: Third response participant B [51]

Image 3 brings the move from Condition 2 into Condition 3B which seems provoked by the contrast of certainty (breasts) followed by uncertainty (morality of looking at naked breasts). The medium sign becomes transformed into a strong sign (normal human body). Again, finding out one is "wrong" creates more intense ambivalence when it follows the assumption that one is "definitely right" rather than the assumption one is "possibly right but also confused." In this case the participant thinks that she has seen breasts and that she has finally made a somewhat descent estimate of the situation. Then, perhaps projectively contextualizing she seems to realize that looking at breasts may be understood as immoral or improper, and for this reason she is suddenly not so clear about the meaning of what she is looking at—what she thought she understood. [52]

While viewing the fourth image the strong sign is undone with the reintroduction of uncertainty to the meaning constructive process (the "surprise" that the woman is actually wearing a sheer black top). The rigid nature of the strong sign (normal part of the body) causes it to fail here as there was no room inside "normal" for the uncertainty of "non-normalcy" in the outfit. The confusion brings the process back to Condition 2 and a state of maximum ambivalence, and then immediately returning to Condition 3B where a new strong sign is constructed "not a normal outfit."

Illustration 19: Fourth response participant B [53]

The imbalance entailed by ambivalence drives the process of semiotic emergence—while being part of that emergence—constantly creating and recreating the meaning constructive process. As such, ambivalence is a profoundly important source for creativity and the construction of signs. New signs arise as individuals consider what they think they know, in relation to what they know they do not understand. This generative process is momentarily halted only when the intensity of ambivalence is falsely and artificially restricted through the use of a strong sign to pre-control the meaning of the future, yet it can be restarted as soon as uncertainty in meaning is reintroduced. [54]

There can be no doubt though, that what we present here is only a beginning to describing how this occurs. Our model does not explicitly explore the relation of the individual level of meaning construction to the social-cultural world, which surely is a part of the construction of any sign. Nor does our model fully unpack the dialogicality of the relationship between certainty and uncertainty. [55]

One important point that can come from the model, however, is to emphasize that the most difficult meaning making situation, or in other words, the one that most strongly pushes for the construction of new semiotic mediators, is not the frequently supposed condition of total uncertainty. Rather, as our model and the corresponding examples illustrate, the psychological situation most likely to lead to such mediators is the situation in which there is quasi-certainty, intermixed with quasi-uncertainty. [56]

There is ambivalence in organism-environment relation—which complements our microgenetic analysis by a phylogenetic one. There are strong evolutionary roots that can explain why the state of quasi-certainty and quasi-uncertainty is the most ambivalent. Every decision an organism makes—to move or not to move—requires coping with uncertainty. Consider an animal that, having decided to run for his life, stops and climbs a tree instead. Indecision at this moment of turning around to find the nearest tree can very well cost him his life if it allows the predator to catch up to him. Continuing to run—and only run—could also cost him his life, yet in providing a clear direction for action, pre-control of the environment makes the most of a limited set of resources (e.g., time to flee, energy to flee with). [57]

We can imagine how an adaptation—such as the ability for symbolic meaning making—potentially evolved because it allowed the organism to consider the consequence of future actions before engaging in them. Even if such reflexivity about the possible future was incorrect (e.g., fear of action under conditions of no danger), it was still adaptive—it would be better to get out of indecision as quickly as possible by forming a sign that clearly directed action (Condition 3B), however narrow (and potentially harmful to survival as well) such a sign might be. [58]

The presentation of the preliminary version of this paper at the European Conference on Developmental Psychology in Milano in September 2003 was made possible thanks to the support by the Hiatt Fund of Clark University's Psychology Department. The authors are grateful to Clara CHU for her assistance in conducting the empirical study.

1) In this role, the signs encoded into environment can be viewed as a cultural-psychological formal analogue to pheromonal communication in animal species. <back>

2) We are obviously aware of the efforts in psychology—represented by the DEWEY-GIBSON tradition of attempting to eliminate the focus on the Subject and the Object, and reduce the perceiving process to the dynamic relation (coordination) of the two. The GIBSONian perspective allows for no distancing concept—and is hence inapplicable to the study of higher psychological functions and their development. Efforts to change it to incorporate the social nature of human development entail importing the notion of distancing (DEL RIO, 2002). <back>

3) Microgenetic studies look at process of construction, hence, it is not the "marks" or "outcomes" that are of interest but the meaning-making progression as it occurs in relation to the words on the scale. <back>

Baldwin, James M. (1915). Genetic theory of reality. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons.

Branco, Angela U. & Valsiner, Jaan (1997). Changing methodologies: A co-constructivist study of goal orientations in social interactions. Psychology and Developing Societies, 9(1), 35-64.

Bullogh, Edwin (1912). "Psychical distance" as a factor in art and an aesthetic principle. Journal of Psychology, 5(2), 87-118.

Cairns, Robert. B.; Costello, E. Jane & Elder, Glen (Eds.) (1996). Developmental science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cupchik, Gerald C. & Winston, Andrew S. (1996). Confluence and divergence in empirical aesthetics, philosophy, and mainstream psychology. In Moton P. Friedman & Edward C. Carterette (Eds.), Handbook of perception and cognition: Cognitive ecology (2nd ed.) (pp.61-85). San Diego, Ca.: Academic Press.

Del Rio, Pablo (2002). The external brain: eco-cultural roots of distancing and mediation. Culture & Psychology, 8(2), 233-265.

Diriwächter, Rainer (2003). What really matters: keeping the whole. Paper presented at the 10th Biennial Conference of ISTP, Istanbul, June, 24.

Gottlieb, Gilbert (1999). Probabilistic epigenesis and evolution. Worcester, Ma.: Clark University Press. [1998 Heinz Werner Lecture]

Josephs, Ingrid E. & Valsiner, Jaan (1998). How does autodialogue work? Miracles of meaning maintenance and circumvention strategies. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(1), 68-83.

Josephs, Ingrid E.; Valsiner, Jaan & Surgan, Seth E. (1999). The process of meaning construction. In Jochen Brandtstätder & Richard M. Lerner (Eds.), Action & self development (pp.257-282). Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage.

Lewin, Kurt (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

Matte Blanco, Ignacio (1975). The unconscious as infinite sets. London: Duckworth.

Matte Blanco, Ignacio (1988). Thinking, feeling and being. London: Routledge.

Peirce, Charles S. (1935). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. 6. Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press.

Siegler, Robert S. (1996). Emerging minds. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sigel, Irving (2002). The psychological distancing model: a study of socialization of cognition. Culture & Psychology, 8(2), 189-214.

Valsiner, Jaan (1997). Culture and the development of children's action ((2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Valsiner, Jaan (2001a). Process structure of semiotic mediation in human development. Human Development, 44, 84-97.

Valsiner, Jaan (2001b). Constructive curiosity of the human mind: Participating in Piaget. Introduction to the Transaction Edition of Jean Piaget's The child's conception of physical causality (pp.ix-xxii). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

Valsiner, Jaan (2002). The concept of attractor: How dynamic systems theory deals with future. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Dialogical Self, Gent, Belgium, October, 19.

Werner, Heinz (1956). Microgenesis and aphasia. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 347-353.

Emily ABBEY is a graduate student in Psychology at Clark University in Massachusetts. She is currently looking at how the construction of meaning in uncertain circumstances relates to identity development. She teaches classes in the areas of developmental and cultural psychology at the College of the Holy Cross.

Contact:

Emily Abbey

Clark University

950 Main Street

Worcester, MA, 01610

USA

E-mail: eabbey@clarku.edu

Jaan VALSINER is the founding editor (1995) of the Sage journal, Culture & Psychology. He is currently professor and chair of Department of Psychology, Clark University, USA, where he also edits a journal in history of psychology—From Past to Future: Clark Papers in the History of Psychology. He has published many books, the most recent of which are The guided mind (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 1998), Culture and human development (London: Sage, 2000) and Comparative study of human cultural development (Madrid: Fundacion Infancia y Aprendizaje, 2001). He has edited (with Kevin CONNOLLY) the Handbook of Developmental Psychology (London: Sage, 2003).

Contact:

Jaan Valsiner

Department of Psychology

Clark University

950 Main Street

Worcester, MA, 01610

USA

E-mail: jvalsiner@clarku.edu

Abbey, Emily & Valsiner Jaan (2004). Emergence of Meanings Through Ambivalence [58 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 23, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501231.

Revised 6/2008