Volume 3, No. 3, Art. 5 – September 2002

Designing Choice Experiments Using Focus Groups: Results from an Aberdeen Case Study

Anne-Marie Davies & Richard Laing

Abstract: This paper describes how focus groups can contribute in the design of choice experiments for use in the urban environment. Focus groups enable researchers to identify changes to the urban environment that the public would like to see take place; first, in terms of redefining the use of an area, and second, in terms of the attributes that could be placed within the redevelopment scene. Four focus groups were held in Aberdeen, Scotland with the purpose of deriving this information. The issues raised by each user group, and how they relate to future work in the project are discussed.

Key words: focus groups, choice experiments, attributes, Aberdeen

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Choice Experiments

3. The Aberdeen Case Study

4. Background to the Focus Groups

5. Format of the Focus Groups

6. Observations from the Focus Groups

6.1 The built environment professionals

6.2 The remaining groups

7. Further Work

8. Summary

The Robert Gordon University, Scotland is undertaking research aimed at developing public participation in the economic valuation of urban environmental attributes. The purpose of the research is to establish the manner in which people attach values to streetscapes. The project combines elements of environmental economics, urban design, computer visualisation, and environmental psychology. [1]

Previous work in the field of urban study and design has established guidelines to be followed in the future development of urban streetscapes. In the United Kingdom, studies commissioned for the redevelopment of a number of major towns and cities have tended to reach similar conclusions, with each making specific recommendations for individual cases (e.g. DAVIS 1995; GILLESPIES 1995, 1997). These studies, whilst concentrating to varying degrees on technical and quality detailing, have also stressed the importance of consulting the public likely to be affected by any changes. The value of such contact is recognised fully, but a robust and viable mechanism for gathering, analysing and presenting views and information is somewhat lacking. [2]

The attainment of socially sustainable development can only be realised by incorporating the public in the decision making process. The research conducted here represents a clear development in environmental value assessment practice, and will contribute to better informed streetscape developments in the future. [3]

The project aims to develop a methodology through which public consultation can be viable, deal with complex changes and issues, and produce meaningful conclusions that can be acted upon by a design team. [4]

Choice experimentation is a technique which can be used to estimate the values which people place on individual attributes, as well as on the quality and quantity of those attributes. Furthermore, values can be placed on different packages of attributes, such as the proportion of trees to open space, the location of plants and flowers within a street, and the mix of street furniture. [5]

In choice experiments, respondents are typically presented with six to ten choice sets, each one containing a base option (typically the status quo or "do nothing" option) and several design alternatives. In each choice set, respondents indicate their preferred option. The attributes within each choice set are varied enabling the researcher to estimate the relative importance of each (BLAMEY, ROLFE, BENNETT & MORRISON 1997). Choice experiments attempt to identify the utility that individuals derive from the attributes of the commodity being valued. This is done by examining the trade-offs individuals make when making choice decisions. [6]

When designing choice experiments, MORRISON, BENNETT and BLAMEY (1997) argue that focus groups are useful in determining which attributes should be included in the choice sets, what information should be included in the questionnaires, trialling alternative questionnaire formats, and detecting bias or other problems. As such, their study used focus groups to explore appropriate types of background information, attributes and photographs to include in the questionnaire, and reactions to the draft questionnaire layout and choice sets. [7]

Unlike the study by MORRISON et al. (1997), the issue of using focus groups to test and refine the choice experiment questionnaire is not discussed here. In the Aberdeen study, focus groups were only used to determine which attributes to include in the choice experiments and the overall research direction (see DAVIES, LAING & MACMILLAN 2000 for a discussion). [8]

To conduct a choice experiment investigating possible urban redevelopment scenarios, a suitable case study area was chosen. The Castlegate Square in Aberdeen, Scotland is boarded on three sides by a number of small, individual businesses including retail shops, pubs, eating establishments, and a number of shop vacancies. The square itself is one of the oldest remaining streets in Aberdeen, and is the historical civic centre of the city (BROGDEN & MCKEAN 1998). Objects located within the square are limited, although the town market cross and a number of benches are present. On one side of the square, several trees have been planted and several types of granite paving make up its surface. Although the Castlegate is located within close proximity to the main shopping district of Aberdeen, it could be viewed as being under-utilised by the public. These characteristics make the Castlegate an ideal area within which to test a range of redevelopment alternatives using choice experiments. [9]

4. Background to the Focus Groups

Four focus groups were held in Aberdeen during February and March 2000 addressing the opinions of several key user groups. The participants comprised of honours year architectural students, business people operating in the Castlegate, members of the general public, members of the Aberdeen City Council, and professional urban designers. The groups ranged in size from three to six participants and each session lasted approximately one hour. Each focus group was comprised of people identified as being from the same or similar user group. [10]

The rationale for conducting a student focus group was that it provided an excellent forum for testing the questions, the location, and the recording equipment before any focus groups involving the public took place. Additionally, it was thought that honours year students would have gained sufficient architectural (and local) knowledge to make a valid design contribution to the project. [11]

The second focus group comprised local business people operating in the Castlegate. In order to ensure a mix of participants, these people were approached in their places of work during business hours and invited to attend. [12]

Members of the general public made up the third focus group. Each participant was a local resident of Aberdeen, and had visited the Castlegate at least once. Each participant was paid £10 to cover any expenses incurred. [13]

The fourth focus group comprised people who had previously been involved in work undertaken in the Castlegate. Attempts were made to recruit a variety of built environment professionals from the public and private sectors, including a landscape architect, a surveyor, a Council member, a representative of the Aberdeen City Centre Partnership, and a representative of Grampian Enterprise. [14]

An additional focus group comprising specifically of Castlegate residents was also organised. However, each of the would-be participants cancelled just prior to the focus group meeting. As such, no resident focus group was held. [15]

In terms of deciding how many focus groups to hold, it was felt that after four, no new information was being produced. The research team therefore decided that holding additional focus groups would simply generate unnecessary work. Furthermore, several of the groups who would be most affected by any redevelopment work in the Castlegate had been given the opportunity to express their views and opinions. [16]

The focus groups were used to identify the criteria and topics respondents felt were of importance to the Castlegate and to urban development in general. The aim was to produce a list of attributes that could later be tested in the choice experiments. [17]

Each focus group was structured in three stages. The first stage introduced the participants to the study and the Castlegate. The second stage involved asking the participants questions and generating discussion, and the third stage examined the conclusions reached. There were also opportunities at the end of each meeting for participants to make more specific inquiries about the project. Each focus group was video taped and subsequently transcribed. [18]

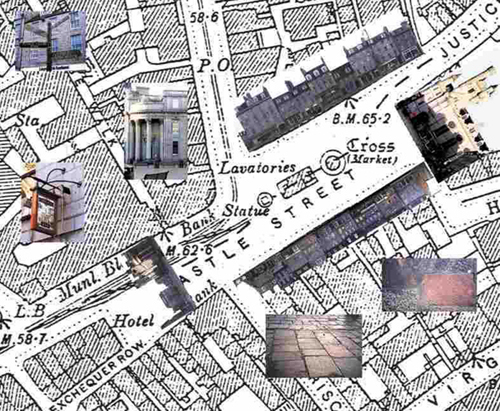

To assist discussion and allow participants to indicate buildings, areas, landmarks or features within the Castlegate, an A0 size poster was prepared and laminated (see Illustration 1). The intention of this was twofold. First, the poster provided a limited amount of information during the early part of the meetings; and second, participants were able to challenge the information presented, write comments as appropriate, and sketch ideas. After each meeting a copy of the modified poster was made, and then the comments erased.

Illustration 1: Castlegate map presented in the focus groups [19]

A question guide was prepared to help ensure that the following issues were addressed in all meetings.

What do participants feel about current utilisation of the area?

Are there any particular issues they feel need addressing?

What do they think about safety in the area?

What do they think about current businesses in the area?

Do participants currently use the area?

If so, in what way?

If not, what might attract them?

Which areas which are currently used, or felt to be attractive?

What future developments might improve the area?

What developments might not?

Can a ranking of the attributes discussed be agreed upon?

Are there any areas of complexity which must be addressed in the choice experiments? [20]

Overall, each focus group meeting tended to follow the above structure, and the questions were discussed as they were posed. Where appropriate, participants were able to deviate from the topic guide if their comments were relevant to the discussion. Each focus group was scheduled to last approximately one hour. The actual length of the focus groups ranged from forty-five minutes to one hour. [21]

6. Observations from the Focus Groups

With the exception of the built environment professional's focus group, each of the groups expressed ideas about redevelopment scenarios and attributes that could be integrated into the Castlegate square. The built environment professionals however, tended instead to stress the importance of providing the public with realistic redevelopment scenarios. While this is important to ensure that the public's confidence in the participation process is not undermined, it was also important that participants were free to make suggestions on what they would like to see happen to the Castlegate. Any suggestions could then be subject to a market feasibility study, which would predict whether or not they would be economically viable. From here, the best use scenario could be determined and used as a basis for the choice experiments. The attributes suggested by the participants can then be integrated into the redevelopment scenario and tested within that context. [22]

6.1 The built environment professionals

In contrast to the other groups, the built environment professionals generally thought that there was nothing intrinsically wrong with the square, and instead was one of the nicest in Scotland. They also felt that the current retail activities were consistent with the residential demands of the area. In this respect, they were against suggestions from the other groups that the Castlegate should be redeveloped into a Grassmarket1) type area. The group was worried that this type of development may lead to an increase in noise, which may affect the residents. [23]

The built environment professional's group was against reopening the Castlegate up to traffic. They argued that allowing traffic through the area would not necessarily increase the amount of people stopping to use the facilities in the square. This group was also cautious of reintroducing market stalls partly due to the variability in previous markets held there, and also because an area known as the Green is now Aberdeen's designated market stall area. Additionally, the Belmont Street area of Aberdeen is currently being upgraded, which includes the introduction of a weekly street market. [24]

While there were similarities between the user groups in terms of redevelopment scenarios being suggested (see Table 1); each group raised a number of unique points based on their own experiences with the Castlegate. For example, the business owners stressed the importance of keeping the carparks behind the Castlegate open as they bring people into the area. This group was also the one most satisfied with the current mix of shops and the most interested in seeing the area reopened to traffic. It was even suggested that the square could be turned into a short stay carpark. The architectural students and the members of the public were less enthusiastic about reopening the square up to traffic—although it was mentioned. [25]

All groups agreed that too many pubs and charity shops currently exist in the square and this would need to be changed in order to attract more people to the area. Unlike the built environment professionals however, the three remaining groups liked the idea of reintroducing market stalls to the square. [26]

In terms of attributes that would improve the visual appearance of the Castlegate, trees were mentioned the most frequently. All the groups agreed that trees would make a positive contribution to the appearance of the Castlegate, helping to break up the space, and create a wind barrier. Additionally, benches placed under the trees would give people a pleasant place to sit and relax.

|

Attributes |

Redevelopment ideas |

|

|

Table 1: Attributes and ideas for redevelopment emerging from the focus groups [27]

The lack of tourist information in the area was of concern to each group. It was generally agreed that given the historical significance of the Castlegate and the attractiveness of the Citadel building, the tourist information office should be located within the Castlegate. It was also suggested that signs and plaques describing the significant buildings and monuments be placed around the square. [28]

In terms of redevelopment scenarios for the Castlegate, two major themes emerged. The first suggestion was a cafe/restaurant/bar district with outdoor dining facilities, and the second suggestion was an arts and cultural district with unique shops and galleries. In theory, both these themes would provide incentives for people to visit the Castlegate; however, an economic feasibility study would need to be undertaken to test their practicality. [29]

Focus groups are helpful in determining what to include in the choice experiments. They are useful for exploring potential changes to an area. As shown by the Aberdeen case study, after several focus groups, participants started expressing similar ideas regarding possible redevelopment scenarios and the types of streetscape attributes that could be located there. From here, a list of all possible attributes that could be included in the choice experiments can be compiled and then refined through surveys. [30]

For the Aberdeen case study, the focus groups provided the researchers with two main objectives. First, several possible redevelopment scenarios for the Castlegate and second, a list of streetscape attributes. The emerging themes for the redevelopment scenarios were a café/restaurant/bar district with outdoor dining facilities, and an arts and cultural district with unique shops and galleries. The suggested attributes for livening up the square include trees, plants, flowers, street lights, floodlights, activities (e.g. markets), seating, signage, artwork, a water feature, tourist information, and better shops. [31]

The next step in designing the choice experiments would be to take several different styles of the attributes discussed in the focus groups and test their suitability in the case study area. This can be done using photographs or visual images, and preference surveys. By looking at the photographs or images, respondents could express their liking of particular designs. Preference surveys could eliminate some styles of attributes thus reducing what has to be shown in the choice experiments. Alternatively, if there are certain styles that appear to be well liked, they should by all means be included. [32]

In this project, focus groups were used to identify possible redevelopment scenarios for the Castlegate, and identify a range of attributes that could be tested within those scenarios. Additionally, focus groups were a useful way of finding out whether the attributes suggested by participants were consistent with those mentioned by urban professionals in design guidelines. [33]

For example, many attributes including trees, landscaping, benches, street art, and water features are widely discussed in the streetscapes literature (e.g. GILLESPIES 1997) and were brought up in the focus groups. However, the focus groups also mentioned several other attributes that could be considered quite unique to the Castlegate. For this reason, focus groups—in addition to design guidelines—are useful in determining which attributes to include in choice experiments. Attributes suggested by the focus groups included tourist information plaques, removal of rubbish, floodlighting the buildings, and outdoor heating lamps for dining areas. [34]

To ensure that focus groups are successful in determining which attributes to test in the choice experiments, the main user groups in the area under investigation need to be identified. Ideally, each focus group should consist of participants from the same user group to ensure that no conflicts of interest arise between groups. By holding focus groups with the relevant stakeholders and incorporating their ideas, it should be possible to produce design concepts that are not too contentious. [35]

The Aberdeen focus groups helped clarify several issues (such as alternative uses for the Castlegate) and identified several important topics which had not previously been considered by the researchers (such as providing a tourist information service). It is felt that the inclusion of focus groups in the process for designing choice experiments is a worthwhile and useful step. [36]

It should be kept in mind that in this study focus groups have served as the first, but not the only step in the participation process. Opportunities for people to have their say will be available in subsequent stages, through preference surveys and in the choice experiments themselves. [37]

The work reported in this paper was jointly funded by Scottish Enterprise and the Robert Gordon University.

1) A central area of Edinburgh containing a mix of pubs, restaurants, shops and flats. <back>

Blamey, Russell K.; Rolfe, John C.; Bennett, Jeff W. & Morrison, Mark D. (1997). Environmental Choice Modelling: Issues and Qualitative Insights. Choice Modelling Research Report No. 4, Canberra: The University of New South Wales.

Brogden, William A. & McKean, Charles (Eds.) (1998). Aberdeen—An Illustrated Guide, Edinburgh: The Rutland Press.

Davies, Anne-Marie; Laing, Richard A. & MacMillan, Douglas C. (2000). The Use of Choice Experiments in the Built Environment: An Innovative Approach, Proceedings of the Third Biennial Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics, May, Vienna: Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration.

Davis, C.J. (Ed.) (1995). Edinburgh Streetscape Manual, Glasgow: Lothian Regional Council.

Gillespies (1995). Glasgow City Centre Public Realm: Strategy and Guidelines, Glasgow: Strathclyde Regional Council.

Gillespies (1997). Streets Ahead: Technical Guidelines for Quality Streetscape Projects, Glasgow: Scottish Enterprise.

Morrison, Mark D.; Bennett, Jeff W. & Blamey, Russell K. (1997). Designing Choice Modelling Surveys Using Focus Groups: Results from the Macquarie Marshes and Gwydir Wetlands Case Studies. Choice Modelling Research Report No. 5, Canberrra: The University of New South Wales.

Anne-Marie DAVIES is a Research Assistant at the Robert Gordon University. Her interests include ways of using environmental economics methodologies, the Internet, and computer visualisations to value public goods and determine preferences for built environment amenities.

Contact:

Anne-Marie Davies

Scott Sutherland School

The Robert Gordon University

Garthdee Road

Aberdeen

AB10 7QB

UK

E-mail: a.m.davies@rgu.ac.uk

URL: http://www.rgu.ac.uk/sss/

Dr Richard LAING is a Senior Lecturer at the Robert Gordon University. He has previously completed research in the fields of built heritage conservation and value assessment, and he is currently working on research concerning streetscape evaluation, the value of urban greenspace, and innovative approaches in housing.

Contact:

Richard Laing

Scott Sutherland School

The Robert Gordon University

Garthdee Road

Aberdeen

AB10 7QB

UK

E-mail: r.laing@rgu.ac.uk

URL: http://www.rgu.ac.uk/sss/

Davies, Anne-Marie & Laing, Richard (2002). Designing Choice Experiments Using Focus Groups: Results from an Aberdeen Case Study [37 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3), Art. 5, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020358.