Volume 2, No. 3, Art. 17 – September 2001

Analyzing Cultural-Psychological Themes in Narrative Statements

Carl Ratner

Abstract: This article describes principles and procedures for rigorously analyzing cultural-psychological themes in narratives. The principles and procedures draw upon phenomenology. The point is to summarize the psychological significances that are manifested in the narrative and then illuminate their cultural character. The summary of psychological significances must be faithful to the subjects' words, yet it also explicates psychological and cultural issues in the statements that subjects are not fully aware of.

Key words: narratives, discourse analysis, phenomenology, cultural psychology, hermeneutics

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Phenomenological Procedure for Identifying Psychological Themes in Verbal Accounts

3. An Application of the Phenomenological Procedure

Verbal accounts (from interviews, narratives, and self-reports) contain cultural themes which need to be explicated. Cultural themes cannot be directly read off from isolated statements. They must be gleaned from a contextual analysis of statements. Such an interpretive act is subject to mistakes unless it is performed in a rigorous and systematic manner. I outline a procedure to provide this kind of rigor. [1]

It draws on the path breaking work of researchers in the tradition of phenomenology (GIORGI, 1975a, 1975b, 1994; FISCHER & WERTZ, 1979; CRESWELL, 1998, pp.271-295) and grounded theory (e.g., STRAUSS, 1987; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990). Although these authors focused on elucidating personal meanings from verbal accounts, I will refine their procedures in order to identify cultural qualities. [2]

2. A Phenomenological Procedure for Identifying Psychological Themes in Verbal Accounts

Interpreting psychological qualities involves boiling down an account to essential themes which can then be summarized. The final summary must accurately reflect all the major themes of the original protocol. And it must only reflect those themes. We don't want to overlook any themes. Nor do we want to add (impose) themes which are foreign to the subject's statement. [3]

The first step is to identify "meaning units" within the document. These are coherent and distinct meanings embedded within the protocol. They can be composed of any number of words. One word may constitute a meaning unit. Several sentences may also constitute a unit. A meaning unit may contain a complex idea. It simply must be coherent and distinctive from other ideas. The meaning unit must preserve the psychological integrity of the idea being expressed. It must neither fragment the idea into meaningless, truncated segments nor confuse it with other ideas that express different themes. [4]

It will be instructive to illustrate this point by identifying the meaning units in an actual interview protocol. I will use as data an account that was published by HIGGINS, POWER, and KOHLBERG (1984). The subject was asked whether a student is morally obliged to offer a ride to another student in the school (whom he did not know) who needs a ride to an important college interview. I shall bracket meaning units that express issues related to the moral obligation of doing favors for strangers.

[I don't think he has any obligation]. If I was in his place and I [didn't know the kid too well], [if I wanted to sleep late], [I don't feel that it is my responsibility] to go drive somebody to their interview, [it is up to them, they are responsible]. If I were going there, [if I had an interview there at the same time, sure I would]. But if I had the opportunity to sleep late and didn't know the kid at all, I wouldn't ...

[People seem to think as long as you have a car they have a ride], and in my opinion it doesn't operate that way. [If I wanted to give him a ride, I will give him a ride], [if I am going there and they want to go there]. It is [my car and I am the one who is driving], and I don't see why I should give him a ride.

It doesn't mean I shouldn't give them a ride, but [if I don't know them well enough], I think [just out of protection for myself and my property], I wouldn't. I think people may say that [being responsible to yourself is more important than other people]. I think there is [an extent where you put yourself first]. And when you [believe in putting yourself first, like I do]...[I don't feel I should be obligated to somebody else's work, especially if I don't know them], I don't think I should give them a ride. (p.91) [5]

Identifying meaning units requires interpretation about what constitutes a coherent and distinct theme. This can only be done after the researcher has become familiar with the entire protocol and comprehends what the speaker is saying. Then the researcher can go back to identify particular themes of this account. The meaning units are only meaningful in relation to the structure of all the units—i.e., in terms of the entire (whole) narrative of which they are parts (cf. RATNER, 1997, pp.136-138). [6]

The selection of meaning units is also guided by the research question. If the question is the relation of fathers and children, then responses which pertain to this issue should be highlighted. Other responses irrelevant to the question should not be identified as meaning units in this research. For example, if the subject says, "we moved to San Francisco in 1994" this has no explicit or implicit significance for his relation with his child. Accordingly, it should not be a meaning unit in this particular research. Of course, if the subject indicates that the move did have some bearing on his relationship with his child then it should be part of a meaning unit that expresses its importance for this relationship. [7]

Rigorously identifying meaning units is crucial because it serves as a basis and justification for all further interpretations that the researcher makes. Any interpretations which the researcher makes can be referred back to these original meaning units. This helps to avoid arbitrary, subjective impressions being imposed on the subject. [8]

After the meaning units have been identified, they are paraphrased by the researcher in "central themes." If the meaning unit is "Oh hell," the researcher may construe this as "anger." "Anger" will be the theme, or central theme, of the unit. [9]

The meaning units of the statement on moral reasoning can be represented by the following central themes:

no moral obligation to drive/help—(meaning unit: I don't think he has any obligation")

don't help distant social relations—(meaning unit: "don't know him well")

self-gratification—(meaning unit: "sleep late"; "put yourself first")

self-responsibility—(meaning unit: "everyone responsible for own self"; "not responsible for others")

help if it's convenient for self—(meaning unit: "if he & I were going to the same place")

people use each other—(meaning unit: "people think as long as you have a car they have a ride")

private property can be used as one desires without obligation — (meaning unit: "it's my car")

self-protection—(meaning unit: "don't know people well"; "out of protection for myself") [10]

The central themes should represent the psychological significance of the meaning units. For instance, when the subject surmises that if he wanted to sleep late he need not worry about driving a schoolmate to an interview, it seems that he is emphasizing his own desire over other people's and that this is a form of self-gratification. Similarly, when he says that it's his car and he is the one driving, the implication is that he can use his property however he wishes and is under no obligation to use it to help another person. Central themes involve interpreting the psychological significance of the meaning unit which is often not explicitly stated. However, the inference must be consistent with the body of statements. [11]

Identifying central themes requires sophisticated interpretation of the meaning unit. The following example from SHWEDER and MUCH (1987) illustrates the process of identifying a statement as "an accusation": Alice (aged four years) is seated at a table. She has a glass full of water. Mrs. Swift (the teacher) approaches and addresses Alice: "That is not a paper cup." "While there is no formal, abstract, or logical feature of the utterance that marks it as an 'accusation,' the context, the discourse, and certain background knowledge makes the teacher's utterance readily identifiable as an accusation." (ibid., p.209) The teacher is clearly implying that Alice was wrong to have used a glass and should have used a paper cup instead. Both Alice and the observer realize that the teacher was making an accusation based upon this implicit rule. [12]

The authors (ibid., pp.210-211) note that

"Determining the meaning of a stretch of discourse is no formal or mechanical matter, but is objectively constrained. It calls for a good deal of prior cultural knowledge...The utterance 'That is not a paper cup' is basically a category contrast, meaning 'That is not a paper cup, it is a glass.' It refers the meaning of the event to what is assumed to be known about the relevant differences between paper cups and glasses (a potential for harm through breakage) ..." [13]

The teacher's statement will only be recognized as an accusation if the listener realizes the implicit distinction between glasses and paper cups, the implicit knowledge that glasses can break and cause injury, and the implicit assumption that young children are insufficiently competent or conscientious to be trusted with the unsupervised use of fragile and potentially harmful materials. A listener who does have knowledge of these background cultural assumptions and distinctions can readily identify the teacher's statement as an intended accusation. [14]

The meaning (which is summarized in the central theme) is not transparent in the explicit words people use. It must be inferred from knowledge of complex implicit rules, assumptions, and distinctions. "We must be concerned not only with what was said but also with what was presupposed, implied, suggested, or conveyed by what was said" (ibid., p.212). The implicit rules, assumptions, and distinctions may refer to unnamed events, rules, beliefs, roles, statuses, and other phenomena. [15]

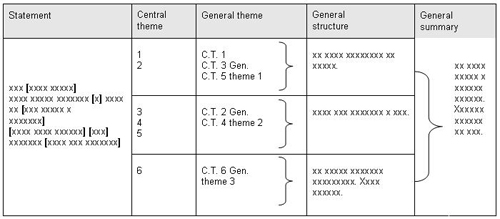

After the central themes have been identified, several related central themes are organized into a category called "general theme." The general theme names the meaning of the central themes. Central themes from throughout the protocol may be related into one general theme. Each general theme is explained/amplified in a "general structure." All the general structures are integrated—compared and explained—in a summary statement, the "general summary." The following diagram depicts the phenomenological procedure just described.

Table 1: Diagram of Phenomenological Method [16]

3. An Application of the Phenomenological Procedure

A useful example of the phenomenological method applied to cultural psychology is CHAO's (1995) research on Chinese and American mothers' beliefs about child rearing. Although CHAO did not follow my procedures, her method is similar in many respects. She asked the mothers to write about their child-rearing values. From the protocols, CHAO noted significant phrases (meaning units), identified themes ("central themes"), and combined these into broader general themes. Central themes from American mothers were "nurturing and patient," "separate the child's behavior from the person," (i.e., criticize behavior but not the child) and "love." CHAO categorized these three "central themes" as expressing a general theme "self-esteem." Her work can be organized into my phenomenological system in the following table. Table depicts the central and general themes from CHAO'S study.

|

American Mothers |

Chinese Mothers |

||

|

Central Themes |

General Themes |

Central Themes |

General Themes |

|

Respect others Respect work Respect money |

Instilling Values |

Good judgment Good person Honesty Responsible Adaptable |

Instilling moral Character |

|

Nurturing and patient |

Independent Self- |

Encourage learning new things |

Independence |

|

Fulfill child’s needs |

Love |

Talk to kids |

Love |

|

Getting in touch with feelings |

Process feelings |

Share toys |

Teach respect for others |

Table 2: Central and General Themes [17]

CHAO explained the significance of the general themes in general structures. She pointed out that independence in children was valued by American mothers for the purpose of encouraging children to separate from the family. Independence was valued by Chinese mothers for the opposite purpose of helping children become successful so they could contribute more to the family. In the same way, love was valued by American mothers as a means to foster self-esteem in their children. Love for Chinese mothers was a means to foster an enduring social relation with their children. [18]

General themes and structures of Chao's work can be systematized and diagrammed in Table below.

|

American |

Chinese |

||

|

General Themes |

General Structures |

General Themes |

General Structures |

|

Independent Self-Esteem |

Independence in order to live on one’s own.Separating self from behaviorInsulates self from criticism directed at behavior. |

Independence |

Independence in order to better provide for family |

|

Love |

Love is valued to foster self-esteem in child |

Love |

Love is valued to foster enduring social relation with child |

|

Process feelings |

To know self better; not to understand other people better |

|

|

Table 3: General Themes and General Structures [19]

In the phenomenological analysis, every stage preserves and illuminates the meaning of the earlier stages. Central themes express the specific psychological meaning of the meaning units; general themes express the meaning of central themes; general structures convey the meaning of general themes; and the general summary explains how all the general structures are interrelated. The summary explains whether structures complement or contradict each other. [20]

Since each higher level of analysis elucidates the specific quality of the lower level, a general theme may have a very different name from the central theme. For example, the central theme of love for American mothers connoted the general theme of independent self esteem, thus, the general theme is not love. Instead, the general theme "love" was used to express the central theme of "make child happy." [21]

The psychological significance of a central theme, rather than the bare words, determine the terminology that is used to identify general themes. [22]

For example, when a factory worker says he uses all the bathroom breaks he can take, it is necessary to identify the specific psychological meaning of this in a central theme. If other parts of the text indicate that he uses breaks to combat management control and exploitation, then this sense should be identified in the central theme. It might be stated as: "Uses breaks to retaliate against management control and exploitation." [23]

LYSTRA used this kind of analysis with great success in an excellent study on the psychology of romantic love (cf. RATNER, 1997, pp.135-136). From meaning units such as "regard me as one with yourself," she identified central themes such as "love is a merging of personal identities," "love is exclusive," "love is a rare match between unique individuals," "love involves revealing personal thoughts and feelings." [24]

When the phenomenological procedure is employed to analyze cultural-psychological phenomena, central themes, general themes, general structures, and the general summary should all emphasize specific content. CHAO indicated the specific quality of independence and love in her general structures. LYSTRA'S central theme, "love is a rare match between unique individuals," also denotes a specific quality of the love feeling. Another example of employing cultural terminology is Gee's interpretation of a woman's statement about her marriage. The "meaning unit" was, "Why in the world would you want to stop and not get the use out of all the years you've already spent together?" Gee designates the "central theme" (meaning) of this statement as: "time spent in marriage is being treated as an `investment'." Investment denotes a particular kind of transaction or relationship. It could be amplified in a general structure to yield: "In terms of the investment metaphor, if we invest money/time, we are entitled to a `return.' So according to this model, it is silly not to wait long enough, having made an investment, to see it `pay off' and be able to `get the use out of' the time/money that has been invested." [25]

Cultural psychologists strive to avoid abstract terminology because it precludes apprehending their specific psychological and cultural character. For example, if the worker's statement "uses all the bathroom breaks he can" is parsed abstractly as "attends to bodily needs" this would obscure the cultural significance that the breaks have for the worker. Literal paraphrasing of a statement similarly expunges its psychological and cultural significance. If the worker's statement, "uses all the bathroom breaks he can," were paraphrased as "takes many bathroom breaks" its psychological and cultural significance would be obfuscated. [26]

Most qualitative researchers are not interested in culture and therefore most of their codes are abstract. For instance, in analyzing a job, STRAUSS codes it as: information passing, attentiveness, efficiency, monitoring, providing assistance, conferring (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1990, pp.64-73). None of these codes elucidates the content or quality of the work. They could just as well refer to a nurse as a prison guard. Both jobs entail STRAUSS's codes and the latter fail to distinguish the vastly different ways that nurses and prison guards treat people. STRAUSS turns even further in the direction of abstractness when he advocates dimensionalizing these codes in terms of their frequency, intensity, and duration. Instead of revealing what the subject concretely does, how she treats people, what her objectives are, and what the institutional pressures are, STRAUSS's procedure leaves us with the abstract knowledge that the subject passes information frequently and for short durations each time. [27]

Even CHAO uses abstract terms such as "processing feelings," "respect work," "instilling values," "moral character," "good person," "adaptable," "talk to kids," "respect others," "honest," "patient." All of these express no specific cultural-psychological content—e.g., in what ways does one respect others (by questioning them closely to find out their feelings or by allowing them a great deal of privacy), how does one talk to kids (as mature adults or as immature children; patiently or impatiently), how does one respect work (to earn money or to build character)? [28]

CHAO could have avoided this problem by identifying concrete meanings at every level of analysis. The central theme "respect work" should have been "respect work to become wealthy," or "respect work to develop a strong ethical code," or "respect work to contribute to society," Providing concrete information in the central themes is the ultimate "thick description" that GEERTZ and RYLE have espoused. "Thick description ... entails an account of the intentions, expectations, circumstances, settings, and purposes that give actions their meanings" (GREENBLATT, 1999, p.16). [29]

Using concrete terms for all the codes enables the cultural psychologists to relate each one to cultural factors and processes. In the case of CHAO's data, we can see the homology between the general structure "independent self in order to live on one's own," and the widespread American value of individual autonomy and the free market where individuals must make their own decisions. This kind of cultural analysis allows us to conclude that certain child rearing values recapitulate and reinforce cultural activities and concepts outside the family. GEE's interpretation of marriage as an investment similarly allows us to note that commercial concepts and practices have penetrated the formerly distinct domain of family life. [30]

A cultural psychological analysis must remain faithful to the subjects' statements, yet must also explicate cultural issues in the statements that subjects are not fully aware of. In other words, statements contain cultural information that is only recognizable by someone who is knowledgeable about cultural activities and concepts. The researcher brings this knowledge to bear in analyzing cultural aspects of the statements. The researcher must use the statements as evidence for cultural issues. Any conclusion about cultural aspects of psychology must be empirically supported by indications in the verbal statements. At the same time, the cultural aspects are not transparent in the statements and cannot be directly read off from them because subjects have not themselves explicitly reflected on or described these aspects. They are embedded in the statements and must be elucidated from them. The task of analyzing descriptive data is to remain faithful to what the subjects say yet also transcend the literal words to apprehend the cultural meanings embedded in the words—just as the physician listens to the patient's report of symptoms and then utilizes medical knowledge to identify what disease the patient has (cf. SCHUTZ, 1967, p.6). [31]

Chao, Ruth (1995). Chinese and American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers' childrearing beliefs. Ethos, 23, 328-354.

Creswell, John (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage.

Fischer, Constance & Wertz, Fred (1979). Empirical phenomenological analyses of being criminally victimized. In Amadeo Giorgi, (Ed.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology (vol.3, pp.135-158). Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, Amadeo (1975a). Convergence and divergence of qualitative and quantitative methods in psychology. In Amadeo Giorgi, (Ed.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology (Volume 2, pp.72-79). Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press.

Giorgi, Amadeo (1975b). An application of phenomenological method in psychology. In Amadeo Giorgi, Constance Fischer (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology: (Volume 2, pp.82-103). Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press.

Giorgi, Amadeo (1994). A phenomenological perspective on certain qualitative research methods. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 25, 190-220.

Greenblatt, Sal (1999). The touch of the real. In Sherry Ortner (Ed.), The fate of "culture": Geertz and beyond (pp.14-29). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Higgins, Ann; Power, Clark & Kohlberg, Lawrence (1984). The relationship of moral atmosphere to judgments of responsibility. In William Kurtines & Jacob Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behavior, and moral development (pp.74-106). New York: Wiley.

Ratner, Carl (1997). Cultural Psychology and Qualitative Methodology. New York: Plenum.

Shweder, Richard & Much, Nancy (1987). Determinations of meaning: Discourse and moral socialization. In William Kurtines & Jacob Gewirtz (Eds.), Moral development through social interaction (pp.197-244). New York: Wiley.

Strauss, Anselm (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, Anselm & Corbin, Juliet (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Carl RATNER has been developing a theoretical and methodological approach to cultural psychology for several decades. He has published Cultural Psychology and Qualitative Methodology: Theoretical & Empirical Considerations (Plenum, 1997) and Cultural Psychology: Theory & Method (Plenum, 2002). RATNER currently gives workshops on qualitative methodology especially in relation to cultural psychology.

His articles can be read on his web site: http://www.humboldt1.com/~cr2

Contact:

Carl Ratner

P.O. Box 1294

Trinidad, CA, 95570, USA

E-mail: cr2@humboldt1.com

Ratner, Carl (2001). Analyzing Cultural-Psychological Themes in Narrative Statements [31 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(3), Art. 17, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0103177.

Revised 6/2008