Volume 9, No. 3, Art. 2 – September 2008

From Local Practices to Public Knowledge: Action Research as Scientific Contribution

Joel Martí

Review Essay:

Kathryn Herr & Gary L. Anderson (2005). The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 157 pages, Paper (ISBN 0-7619-2991-6), € 25,19, Cloth (ISBN 0-7619-2990-8), € 47,18

Abstract: In recent years action research has been gradually introduced into academic thought, giving impetus to contributions such as The Action Research Dissertation, specifically aimed at doing and reporting doctoral research based on this methodology. Beyond purely instrumental aspects (contributing criteria and tools for the execution of dissertations through action research), the book raises some issues that play a fundamental role in assessing action research at the university level: its epistemological bases, researchers' positionality, quality criteria, and the ways in which the process is narrated.

This review essay introduces the debate (Section 1), reviews the chapters of the book (Section 2), and notes its contributions to this ongoing discussion and where it falls short, and, more generally, on the relation between universities, action research, and social practices (Section 3).

Key words: action research; dissertations; university; quality; positionality; participation

Table of Contents

1. The Starting Point: "Activism", Research and University

2. The Action Research Dissertation: Comment on the Contents

2.1 Second Chapter: Action research traditions

2.2 Third Chapter: Positionalities of the action researcher: insiders and outsiders

2.3 Fourth Chapter: Rethinking validity—quality criteria for AR

2.4 Fifth Chapter: Research design, the dissertation and its defence

2.5 Seventh Chapter: Ethical issues

2.6 Sixth Chapter: From action research to dissertation—some examples

3. Contributions, Lacunae and Some Topics for Debate

3.1 Coming full circle: The returning of the scientific work to the social practice

3.2 Can AR survive in academe?

3.3 AR is not only constructed from within the academe

1. The Starting Point: "Activism", Research and University

Today, action research (AR) is not only becoming more consolidated among practitioners in fields such as education, and social work, and is also being progressively incorporated into academic reflections on research and finding its way into course syllabi and scientific publications.1) [1]

This growth is accompanied by the need to establish these methods as relevant techniques for producing differentiated knowledge of the "traditional" methods of social research. An important part of the literature in the field includes analyses of the epistemological foundations and methodological designs, based on different research traditions, of these approaches; those contributing to this literature include ARGYRIS, PUTNAM and SMITH (1985), FALS BORDA (1994), GREENWOOD and LEVIN (1998), HERON (1996), KEMMIS and MCTAGGART (1987), RODRÍGUEZ VILLASANTE (1998); in addition to the exhaustive compilation organised by REASON and BRADBURY (2001), which has become an essential reference in the field. Other more specific contributions have focused on defining criteria of rigour and quality for AR; e.g., AVISON, BASKERVILLE and MYERS (2001), BRADBURY and REASON (2001), CHANDLER and TORBERT (2003), CHECKLAND and HOLWELL (1998), FELDMAN (2007), HEIKKINEN, HUTTUNEN and SYRJÄLÄ (2007), HOPE and WATERMAN (2003), REASON (2006), TORBERT (2000), TURNOCK and GIBSON (2001). A third group of contributions has emphasised how these practices can be presented to the scientific community and, more specifically, how to do this through academic dissertations. Within this latter group of texts, which is more specific than the others, we can include the works of ANDERSON and HERR (1999), COGHLAN and BRANNICK (2001), DAVIS (2004), GROGAN, DONALDSON and SIMMONS (2007), FISHER and PHELPS (2006), HASLETT et al. (2002), REASON and MARSHALL (2001), ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER (2007), ZUBER-SKERRITT and PERRY (2002); as well as several online resources maintained by DICK (1993, 1997, 2000 & 2005). [2]

The book The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty, written by Kathryn HERR and Gary L. ANDERSON which has given rise to this essay, is a text that can be included in this third group of contributions: it is a guide intended for both doctoral students and their committee members, focusing on criteria for doing, reporting, and evaluating dissertations in the AR field. Although the book is brief, it deals with topics that play a key role in legitimising AR in the academic community: its epistemological foundations, the researcher's positionality, the quality criteria or the ways in which the AR process is narrated and reported. All this is done based on "what is expected" in university research. [3]

This is no minor issue, since defending, debating and approving a dissertation involves, above and beyond its ritual nature, the evaluation of certain research practices by what we could call the "scientific community", and its acceptance as a relevant form of producing knowledge within the framework of the social sciences. In this respect, the book enables several important topics to be considered: What is the academic community "asking" of AR? What is AR "offering" the academic community? How can AR "defend itself" from the "methodological conservativeness" of certain faculties and academic practices? [4]

In view of the fact that university contexts are quite diverse, the book offers no extensive response to these questions, but it does offer several key insights for the AR-university debate. The authors have broad experiences in the field of education and, following years of working with doctoral students, they make contributions that are based on these university experiences. Some people will consider this book a practical tool for their present or future projects and some may see it as a recognition of AR in the university context; others, who are not as familiar with these approaches, will see it as a methodological discovery, and others, perhaps, will consider it a provocation, as is the case of Patricia MAGUIRE who, 20 years ago, received the following response from a member of her thesis committee while reading her thesis: "If you want to do research, do research; if you want to organize, then go do activist work" (MAGUIRE, in HERR & ANDERSON, 2005, p.xii). A comment that, despite the progress made and 20 years on, can still be heard in some faculties and disciplines. Kathryn HERR and Gary L. ANDERSON turn this argument around, by addressing the issues that give rise to such comments. [5]

The book was written in the US and focused on the US. Therefore, some considerations made by the authors need to be reinterpreted in order to adapt them to a different reality. In any case, the book is a good starting point about how AR can contribute not only to change in local contexts, but also change in the university itself; changes in ways of knowing, and also changes in how universities relate to the societies of which they form a part. Action research has something to say on this, and that one specific but fundamental way to promote this dialogue is through the doctoral dissertations debate. [6]

2. The Action Research Dissertation: Comment on the Contents

Although presented as a "guide" for students, the book by Kathryn HERR and Gary L. ANDERSON does not merely deal with basic questions about the design of AR or an academic dissertation, since it is assumed that readers have a previous methodological background,2) and for this reason it focuses directly on certain topics of AR which the authors regard as "unique dilemmas": Methodological Traditions (Chap. 2), Positionality (Chap. 3), Quality (Chap. 4), Design, Writing and Defence (Chap. 5) and Ethics (Chap. 7). Chapter 6 presents three works that use AR in their development, with different characteristics and based on different approaches. Each chapter is a separate entity, and can be read in a different order for purposes of consultation. The first chapters review previous works by the same authors (ANDERSON & HERR, 1999; ANDERSON, HERR & NIHLEN, 1994; ANDERSON & JONES, 2000), thus, the primary texts can be used for reading the contents in greater depth. [7]

The starting point, drawn in the Preface and Chapter 1 (Introduction) of the book, is the counterpositioning of practising AR and its academic presentation as a scientific contribution. Whereas the interest of an AR proposal is focused on producing knowledge (and action) that is shared by the members of an organisation/community being studied and that can be used by the participants to act in their own settings, an academic dissertation requires that, beyond its use within a specific framework of study, this practice be transferable in such a way that its application can be seen not only in the specific setting in which it has been developed, but also in other settings. In other words, a dissertation is about constructing knowledge at a more general level. In this respect, HERR and ANDERSON use and adapt the distinction made by COCHRAN-SMITH and LYTLE (1993) between local knowledge and public knowledge. [8]

Moreover, one of the defining characteristics of AR is the construction of knowledge from many sources, which each tradition conceptualises in a different way, but which, expressed in synthesis, implies a relation of dialogue and synergy between and among knowledge sources. This knowledge is therefore often collaborative and collective, and on many occasions, the reports (written, visual, etc.) are drawn up and signed jointly: not only does the participant participate, but he or she is also a "co-researcher". On the other hand, an academic dissertation is an individual work through which a person obtains an assessment of individual skills and an academic title, regardless of whether the results of that project may affect the local setting under study. [9]

The differences between putting action research into practice and reporting an academic proposal form the basis that can lead part of the academic community to resist these methods, and precisely these differences form the basis for the contributions of Kathryn HERR and Gary L. ANDERSON. They affect the foundations and justifications that are necessary in a dissertation, and also their development and the ways of reporting the research. [10]

2.1 Second Chapter: Action research traditions

The foundation and contextualisation of the methodological approach chosen is an essential task in any research project, but even more so in an AR dissertation, in which the "originality" of the method is usually "penalised" with stricter requirements in terms of justification. HERR and ANDERSON draw a brief review of different AR traditions: the intention of the book is not to go into great detail since the reader can consult general works such as those of REASON and BRADSBURY (2001) or other original works. In particular, the following are presented: AR and organisational development (GREENWOOD & LEVIN, 1998), action science (ARGYRIS et al., 1985), participatory research (FALS BORDA, 2001), participatory evaluation and participatory rural appraisal (STAKE, 1975; CHAMBERS, 1994), autoethnography and AR as self-study (REED-DANAHAY, 1997; BULLOUGH & PINNEGAR, 2001), and different traditions from the educational field (ANDERSON et al., 1994; COCHRAN-SMITH & LYTLE, 1993; KEMMIS & MCTAGGART, 1987; LIEBERMAN & MILLER 1984; LISTON & ZEICHNER, 1991). [11]

Others approaches from French and Spanish-speaking countries could be added to the ones presented by the authors, since, as fewer texts have been published in English, they are given less importance in contributions from English-speaking countries: these include, e.g., institutional analysis (LAPASSADE, 1975), sociological intervention (TOURAINE, 1978), or sociopraxis (RODRÍGUEZ VILLASANTE, 1998). With respect to both these and the previous traditions, readers should consult the original texts to obtain a deeper understanding of the approaches and authors, since they will find an anchoring point from which to "defend" their position. [12]

In all cases, this brief review allows the authors to define some of the practices that differentiate them and are essential in the epistemological and methodological foundation of dissertations: (a) their orientation towards the group or individual; (b) the "transformative" or "improving" nature of the practices and individuals; (c) the extent to which the participants are involved. However, although an academic work requires a great deal of reflection on these issues, they are not strongly developed in the book. [13]

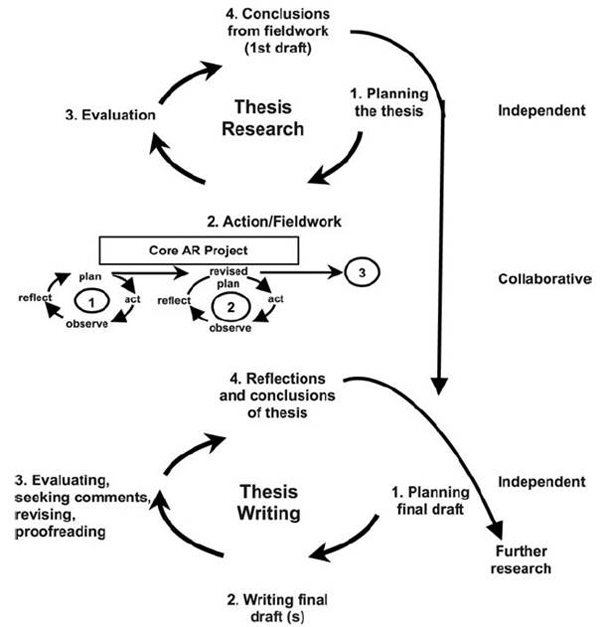

Finally, the chapter includes a section on the work of Jürgen HABERMAS (1971), in which the authors raise the question of the non-neutral nature of scientific knowledge. Based on this, several critical appreciations are made about power and "conservatism" in AR that refute the alleged emancipatory nature of the methodology per se: "there is nothing in current approaches to action research or reflective practice that might interrupt the mere reproduction of current 'best' practices that support the current social order" (HERR & ANDERSON, 2005, p.26). [14]

2.2 Third Chapter: Positionalities of the action researcher: insiders and outsiders

As the distance between researcher and participants is a basic issue in social research and the specificities of AR are important here, HERR and ANDERSON give special attention to the positionality of the researcher. The authors base their arguments on the distinction between insider and outsider drawn by COCHRAN-SMITH and LYTLE (1993), and develop the following continuum with respect to different possibilities that can be identified in AR:

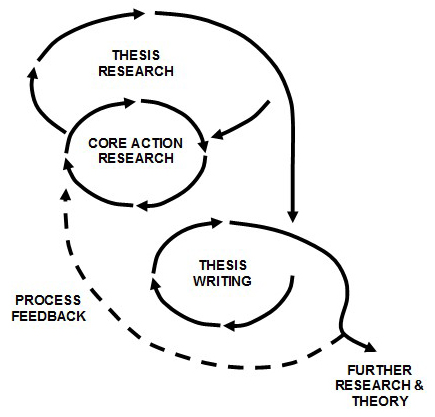

Insider (the researcher studies and changes his or her own practice),

Insider in collaboration with other insiders,

Insider(s) in collaboration with outsider(s),

Mutual collaboration (teams of insiders-outsiders),

Outsider(s) in collaboration with insider(s),

Outsider(s) studying insider(s). [15]

Whereas a university researcher will adopt positions 4 to 6 (unless, of course, he or she is doing AR in the university itself), a doctoral student who is writing a disseration on AR will adopt any of the positions. And the implications of this positionality are epistemological, methodological, and technological. For instance, position (1) will require the exercise of self-observation and self-distancing; position (2) will tackle tensions and conflicts arising from the power relations between the organisation/community members in which the project is being carried out, and the difficulties of tackling them while being part of that organisation/community; in positions (3), (4), and (5) it will be necessary to face the social relations in which different interests converge: the ones of the participants (with interests in producing change within their own practices, each one based on his or her own position) and the ones of the external researchers (e.g., academics with specific incentives for publishing results). Case (6) describes "conventional" research on AR projects or AR methods. [16]

Each of these positions affects the writing of an AR dissertation. There is no doubt that more insider positions contrast with positivist approaches, and for this reason HERR and ANDERSON issue a warning about the error of presenting oneself as an outsider trying to adopt the objective approach of an external observer when one is really an insider (outsider-within). A position that ignores the potential of studying practices and discourses "from inside" and ends by considering the action of the practitioner-researcher a "problem" due to reactivity. [17]

The debate on the researcher's positionality is also related to the question of power relations, in which the researcher is immersed: professional status in the organisation/community under study; position in terms of class, gender, age or ethnicity in relation with the participants; position in (post)-colonial relations between states. These relations of power are present and affect any research project, but in the case of AR they are within the method itself, and therefore require special attention both in terms of designing the process and in terms of the discourse of the academic dissertation itself. [18]

2.3 Fourth Chapter: Rethinking validity—quality criteria for AR

In recent years there has been an increase in contributions to the literature on the "quality" and "validity" of AR. This interest can be justified by several factors: First is the wish to debate and co-construct criteria and working methods among researchers and practitioners who, even though they share the fundamentals of AR, work in different contexts and methodological traditions; second is the need to consolidate these research practices in the eyes of the academic community. [19]

Despite the existing diversity in approaches and definitions, these contributions have something in common when initiating the debate on quality criteria; specifically they have a clear desire to move away from the classic notions of validity established by CAMPBELL and STANLEY (1963). The emphasis on action and the learning of participants place it in an epistemological setting that is different from other methodologies; and, therefore, it is necessary to establish specific criteria. [20]

This is the stance adopted by HERR and ANDERSON who, referring to earlier works (ANDERSON et al., 1994), propose five criteria for AR: "outcome validity" (the extent to which actions occur which lead to the resolution of the problem), "process validity" (method and forms of relation with participants), "democratic validity" (presence of all parties at stake), "catalytic validity" (ability of the participants to know and transform reality) and "dialogic validity" (review by others). These criteria are presented and discussed in relation with the proposals of BRADBURY and REASON (2001) in the Handbook of Action Research. However, the relation between quality criteria in AR and researchers' positionality is less well developed. This is introduced in the previous chapter, but not systematised or developed in this one, nor does it form a part of the debate on the difference between "process quality" and "dissertation quality": Should both issues be judged based on the same parameters? [21]

The chapter also deals with other aspects associated with quality: bias in AR, the question of transferability (from local knowledge to public knowledge), and a third aspect that takes us back to power—the politics of AR. A question (politics) that the authors quite rightly place in the quality chapter, since social groups, their interests and power relations are not in the context of AR but "inside" the method. [22]

2.4 Fifth Chapter: Research design, the dissertation and its defence

This chapter deals with more operative aspects that have to do with planning, writing, and reporting dissertations, paying special attention to particularities that should be taken into consideration in the case of AR. [23]

In writing the dissertation proposal the authors stress the importance of giving solid grounds for the questions forming the basis of the research: from defining the research questions and values implicit in them, to the relevance of using an AR approach and the implications of the researcher's positionality in the process. These grounds are of capital importance in AR dissertations, since many committee members may consider these methods to be quite unfamiliar. Likewise, initiating the AR spiral prior to presenting the proposal may help to test the opportunities and threats to the process, evaluate the time required and help to define it. [24]

In writing the research report the specificities of AR must also be considered. Readers who are less familiar with these methods will quickly search for the research "findings", whereas an AR dissertation usually focuses more on the process. Again, explaining the AR epistemology can show how the conceptual opening permits better comprehension of the studied phenomenon, which will perhaps involve fewer answers and more questions. [25]

Dissertation defences may take different directions, depending on the rituals established in each academic context: if it is considered yet another step in a project that must be subsequently reviewed or as a "final celebration" of something that has already been completed; whether or not it is reported orally and whether it is open to the public (and in particular, to the presence of participants) or not. Of course, anything that has to do with the composition of the dissertation committee and its "proximity" to AR is also important, although HERR and ANDERSON focus their thoughts on the US context. As ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER (2007) note the situation can change considerably in a context such as Germany, where "the first examiner is the supervisor and the second examiner is a professor—often from the same university—selected by and known to the supervisor and in most cases also to the respective candidate" (p.414); in English-speaking universities "the supervisor is the student's teacher, mentor, and advisor, but not an examiner"; and in Spain the director does not usually form a part of the committee but proposes it. The more similar the system for selecting the committee members is to the double-blind review system of refereed journals the "worse" things will be for the defence of non-conventional methodologies; for while authors submit their articles to be reviewed in appropriate journals, in selecting the dissertation committee members, this margin of decision may sometimes not exist. [26]

2.5 Seventh Chapter: Ethical issues

The Belmont Report issued in 1978 in the US by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, established the basic principles for tackling ethical issues that involve individuals taking part in research and is usually the starting point for debates on this topic. In AR, these issues have been dealt with in recent years: COGHLAN and SHANI (2005), LÖFMAN, PELKONEN and PIETILÄ (2004), MORTON (1999), WALKER and HASLETT (2002), WILLIAMSON and PROSSER (2002), ZENI (2001). [27]

HERR and ANDERSON deal with this issue by focusing on the requirements that, in the US academic context, are demanded of projects carried out with public financing or are sponsored by institutions receiving governmental support; an independent ethical Institutional Review Board (IRB) formed by members who have no role in the research review and approve all research proposals whose design involves human participants. [28]

Here, again, AR proposals enter into conflict with traditional research evaluation parameters. The relationship between the researcher and the participant changes subject to the interests of both parties and is not predictable from the start. This gives rise to issues such as informed consent. The weighing of benefits and risks requires a specific approach, since the development of the process depends not only on the researcher but also on the participants (as happens, too, with ethnographic research). [29]

However, the authors do not consider this issue outside of the US context, where regulatory control of the ethical aspects of research is quite diverse depending on each country and discipline. Although it is a widely generalised practice in the biomedical field (e.g., with clinical trials for new treatments), internationally, the situation with respect to social sciences is much more diverse and includes institutional regulation (centralised or de-centralised), ethical codes and recommendations (implemented by associations and professional bodies) or the non-existence of specific guidelines. [30]

2.6 Sixth Chapter: From action research to dissertation—some examples

With a view to analysing the aspects considered in greater depth, and in particular if the interest of the reader is in writing an AR dissertation, in addition to consulting publications such as the one by HERR and ANDERSON, works already written and reported should be consulted. [31]

Although the book already contains many references to written works, the authors also devote one chapter to reporting in greater detail three dissertations written (or currently being written) based on different positionalities and approaches. The three cases come from US universities, so the reader should decide whether it is advisable to complete, compare or substitute these readings for others from their own countries or universities (today, the great number of international, national, and university catalogues on dissertations that can be consulted online include aspects ranging from the title and abstract of the reports presented to the full text). With respect to the present text, we shall make a brief reference to the works included in the book. [32]

The first of these (MOCK, 1999) is in the field of community psychology and focuses on the development of leaders in the Afro-American community of southern Chicago. This is a project that can be included in the centre of the insider-outsider continuum since it is based on mutual collaboration between external researchers and community agents. The second thesis (MCINTYRE, 1995) is in the educational field, in a more external positionality: i.e. a doctoral student requesting a group of teachers to conduct participative research for exploring white "racial" (sic) identity; the proposal deals with the conflicts arising from the external imposition of research agendas. The third case (DYKE, 2003) corresponds to a work in progress conducted by an insider within his or her own working environment. The research is focused on the decision-making process regarding the custody of minors by a team of professionals from Child Protective Services, in which the author is employed. [33]

These are quite different works in terms of positionality, topic and approach, but they all have a common denominator, that of dealing not only with knowledge and intervention in a local research setting, but also the production of more general knowledge for the scientific and professional community. [34]

3. Contributions, Lacunae and Some Topics for Debate

To synthesise, the book under review makes a twofold contribution; a more instrumental one (providing tools for writing doctoral dissertations based on methodological approaches that are less common in the academic community), and another, more strategic one, with respect to relations with the university (raising certain issues that are of key importance in the AR-academe debate). [35]

Reading the book makes it possible to review the basis of AR, although previous theoretical and practical knowledge on these methodologies will ensure better comprehension. In any case, it may need to be complimented with other readings. The fact that the book is so brief makes it impossible to tackle the tensions and challenges posed in any depth, and these are often resolved by the authors in an instrumental and consequently, superficial way. For this reason, and for the implications of the topics it deals with, in some cases the reading raises more questions, debates, and challenges than responses. [36]

The difference between an "AR process" and an "AR dissertation" is not systematised, although it is the underlying theme of the book. This may lead to difficulties in distinguishing between aspects that refer to "how to do good AR" and those that refer to "how to do a good AR dissertation", especially in the case of novice researchers. These aspects, although closely related, are conceptually different, as shown in ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER (2007): core action research is where the classic plan-act-observe-reflect spiral is located, and in turn constitutes the basis of reflection for generating a product (the individual work of the researcher) which is the dissertation. Whereas the first process is targeted at the participants and the local setting in particular, the second process is transferable and targeted at the academic community. Whereas the first is collaborative/participative, the second responds to individual effort: it requires project planning (which obviously revolves around the AR process), an evaluation thereof and theorising which, although supplied with feedback from the AR process, is "closed" over and above the work teams and collaborative dynamics. [37]

Readers from outside US must complete or adapt both the literature review and the references to the social and academic context to their own setting.

Figure 1: Core AR and thesis in ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER's schema (2007, p.421) [38]

Recommendations for further reading include: FISHER and PHELPS (2006) who explore in an original way the challenge to academic conventions when doing an AR dissertation; ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER (2007) and DICK (1993, 1997, 2000, 2005) who present structured approaches for writing AR dissertations; other references made in this text for specific issues; and works of each country for a contextualised view. [39]

3.1 Coming full circle: The returning of the scientific work to the social practice

AR needs academe. As the authors write in the last paragraph of the book (HERR & ANDERSON 2005, p.128):

"By going public with our work, we learn from and inform each other, pushing our respective fields of study as well as the methodology itself. By doing this, we come full circle: In the documenting of the change effort, academe too is potentially challenged to encompass methodological progressions and breakthroughs." [40]

This is the objective that HERR and ANDERSON propose in their book, but it is not the only consequence of the academic reflection about AR. In addition to the construction of theory and methodological innovation, this reflection in turn allows for the production of feedback in local AR practices. Firstly, when researchers are insiders in local settings, dissertations help them to introduce method and reflection in their everyday work. Secondly, and in any case, a dissertation allows to introduce external and theoretical reflection into the AR process as a whole. This argument allows for the enrichment of the ZUBER-SKERRITT and FLETCHER (2007) schema for including a last circle towards the core AR process, from which doctoral students can return to the organisation/community the understanding they have gained through their dissertations.

Figure 2: Process feedback from doctoral work (Source: adapted from ZUBER-SKERRITT & FLETCHER, 2007, p.421) [41]

3.2 Can AR survive in academe?

There is probably no single response to this question. The acceptance of AR is quite different, depending on the country, discipline, and department in question (whether or not there are research groups working on these topics and the position of these groups in the institution itself). The response given by HERR and ANDERSON within this context can be considered possible: we should adapt to the formal and methodological requirements of the academic dissertations, while respecting the essence of AR, we should train supervisors in AR, so that they can guide them and we should disseminate AR in the scientific community in order for it to be better understood. [42]

Although the book explains what doctoral students should do to "play their part", it explains little about what must be changed in the academic community. The lucid diagnosis of Boaventura de Sousa SANTOS (2005, 2007) on present-day universities and their commitment to what he calls the sociology of emergences may contribute a great deal to this debate, which is not purely methodological. [43]

3.3 AR is not only constructed from within the academe

In this text—and in the reviewed book—the reflections have revolved around dialogue between AR and academe. AR needs this dialogue with the academic community as a bridge between social practice and scientific activity, since it feeds off its theoretical and methodological reflections. Through the reporting of doctoral dissertations, this dialogue is done in one context, that of the university. And in this context, the relation is asymmetrical as it lays down the rules of the game. [44]

However, the raison d'être of AR is dialogue with the participants; dialogue about what AR is and what it is not, about researchers' roles and positionalities, about the "quality" sought in a process or about the ethical parameters on which it is based. All this concerns not only academic thinking, but also the participants. In this respect, it would be a good idea to open up more symmetrical communicative spaces between the academic community and local practices. [45]

In this context, HERR and ANDERSON's book is only one step further to consolidate AR as an epistemological approach for analyzing and transforming social realities. The next steps must point to a reflection about universities' role in the construction of shared knowledge and values, and also to redefine their relation with social agents, which are not only public or private actors. [46]

1) A sound indicator of this is the increasing number of articles recorded in the SSCI (Social Science Citation Index) with "action research" as a topic, which in 1999 surpassed 100 articles, reaching 167 in 2007. <back>

2) However, anyone wishing to consult references about it should read DICK (1993, 1997, 2000). Although, as the authors state (p.xvii), people interested in using linear, closed schema to develop their projects should not select an AR approach. <back>

Anderson, Gary L., & Herr, Kathryn (1999). The new paradigm wars: Is there room for rigorous practitioner knowledge in schools and universities? Educational Researcher, 28(5), 12-21.

Anderson, Gary L., & Jones, Franklin (2000). Knowledge generation in educational administration from the inside-out: The promise and perils of site-based, administrator research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(3), 428-464.

Anderson, Gary L.; Herr, Kahtryn, & Nihlen, Ann Sigrid (1994). Studying your own school: An educator's guide to qualitative practitioner research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Argyris, Chris; Putnam, Robert, & Smith, Diana McLain (1985). Action science: Concepts, methods, and skills for research and intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Avison, David; Baskerville, Richard, & Myers, Michael (2001). Controlling action research projects. Information Technology & People, 14(1), 28-45.

Bradbury, Hillary, & Reason, Peter (2001). Conclusion: Broadening the bandwidth of validity: Issues and choice-points for improving the quality of action research". In Peter Reason & Hillary Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participatory inquiry and practice (pp.447-55). London: Sage.

Bullough, Robert V. Jr., & Pinnegar, Stefinee (2001). Guidelines for quality in autobiographical forms of self-study research. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 13-22.

Campbell, Donald Thomas, & Stanley, Julian C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research on teaching. In Nathaniel L. Gage (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp.171-246). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Chambers, Robert (1994). The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development, 22(7), 953-966.

Chandler, Dawn, & Torbert, Bill (2003). Transforming inquiry and action by interweaving 27 flavors of action research. Action Research, 1(2), 133-152.

Checkland, Peter, & Holwell, Sue (1998). Action research: Its nature and validity. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 11(1), 9-21.

Cochran-Smith, Marilyn, & Lytle, Susan (1993). Inside/outside: Teacher research and knowledge. New York: Teachers College Press.

Coghlan, David, & Brannick, Teresa (2001). Writing your action research dissertation. In David Coghlan & Teresa Brannick (Eds.), Doing action research in your own organization (pp.124-133). London: Sage.

Coghlan, David, & Shani, Rami (2005). Roles, politics and ethics in action research design. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 18(6), 533-546.

Davis, Julie (2004). Writing an action research thesis: One researcher's resolution of the problematic of form and process. In Erica McWilliam, Susan Danby & John Knight (Eds.), Performing educational research: Theories, methods and practices (pp.15-30). Flaxton, Qld, Australia: Post Pressed.

Dick, Bob (1993). You want to do an action research thesis? Resource Papers in Action Research, http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/art/arthesis.html [Date of access: January 7, 2008].

Dick, Bob (1997). Approaching an action research thesis: An overview. Resource Papers in Action Research, http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/arp/phd.html [Date of access: January 7, 2008].

Dick, Bob (2000). Postgraduate programs using action research. Resource Papers in Action Research, http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/arp/ppar.html [Date of access: January 7, 2008].

Dick, Bob (2005). Making process accessible: Robust processes for learning, change and action research. International Management Centres Association, http://www.uq.net.au/~zzbdick/dlitt/ [Date of access: January 7, 2008].

Dyke, John Mark (2003). An examination of how child protective staff make decisions with-one-another. Dissertation proposal, University of New Mexico.

Fals Borda, Orlando (1994). El problema de cómo investigar la realidad para transformarla por la praxis. Bogotá: Tercer Mundo.

Fals Borda, Orlando (2001). Participatory (action) research in social theory: Origins and challenges. In Peter Reason & Hillary Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp.27-37). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Feldman, Allan (2007). Validity and quality in action research. Educational Action Research, 15(1), 21-32.

Fisher, Kath, & Phelps, Renata (2006). Recipe or performing art?: Challenging conventions for writing action research theses. Action Research, 4(2), 143-164.

Greenwood, Davydd J., & Levin, Morten (1998). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Grogan, Margaret; Donaldson, Joe, & Simmons, Juanita (2007). Disrupting the status quo: The action research dissertation as a transformative strategy, http://cnx.org/content/m14529 [Date of access: January 7, 2008].

Habermas, Jürgen (1971). Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon Press.

Haslett, Tim; Molineux, John; Olsen, Jane; Sarah, Rod; Stephens, John; Tepe, Susanne, & Walker, Beverly (2002). Action research: Its role in the university/business relationship. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 15(3), 437-448.

Heikkinen, Hannu L.T.; Huttunen, Rauno, & Syrjälä, Leena (2007). Action research as narrative: Five principles for validation. Educational Action Research, 15(1), 5-19.

Heron, John (1996). Co-operative inquiry: Research into the human condition. London: Sage.

Hope, Kevin W., & Waterman, Heather A. (2003). Praiseworthy pragmatism? Validity and action research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(2), 120-127.

Kemmis, Stephen, & Mctaggart, Robin (1987). The action research planner. Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University Press.

Lapassade, Georges (1975). Socioanalyse et potentiel humain. Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

Lieberman, Ann, & Miller, Lynne (1984). School improvement: Themes and variations. Teachers College Record, 86, 4-19.

Liston, Daniel P., & Zeichner, Kenneth M. (1991). Teacher education and the social conditions of schooling. New York: Routledge.

Löfman, Päivi; Pelkonen, Marjaana, & Pietilä, Anna-Maija (2004). Ethical issues in participatory action research. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18, 333-340.

McIntyre, Alice (1995). Making meaning of whiteness: Participatory action research with white female student teachers (Doctoral dissertation, Boston College). Dissertation Abstracts International, 57, 175.

Mock, Lynne (1999). The personal visions of African-American community leaders (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1999). Dissertation Abstracts International, 60, 6424.

Morton, Alec (1999). Ethics in action research. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 12(2), 219-222.

Reason, Peter (2006). Choice and quality in action research practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 6(15), 187-203.

Reason, Peter, & Bradbury, Hillary (Eds.) (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Reason, Peter, & Marshall, Judi (2001). On working with graduate research students. In Peter Reason & Hillary Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp.413-419). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Reed-Danahay, Deborah (1997). Auto/ethnography: Rewriting the self and the social. New York: Berg.

Rodríguez Villasante, Tomás (1998). Cuatro redes para mejor vivir. Buenos Aires: Lumen.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa (2005). La universidad en el siglo XXI. Para una reforma democrática y emancipadora de la universidad. Mexico: UNAM.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa (2007). El Foro Social Mundial y el auto-aprendizaje: La Universidad Popular de los Movimientos Sociales. Theomai: Estudios Sobre Sociedad, Naturaleza y Desarrollo, 15, 101-106.

Stake, Robert (Ed.) (1975). Evaluating the arts in education: A responsive approach. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Torbert, Willian R. (2000). Transforming social science: Integrating quantitative, qualitative, and action research. In Francine Sherman & William R. Torbert (Eds.), Transforming social inquiry, transforming social action (pp.67-92). Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Touraine, Alain (1978). La voix et le regard. Paris: Le Seuil.

Turnock, Christopher, & Gibson, Vanessa (2001). Validity in action research: A discussion on theoretical and practice issues encountered whilst using observation to collect data. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(3), 471-477.

Walker, Beverly, & Haslett, Tim (2002). Action research in management—Ethical dilemmas. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 15(6), 523-533.

Williamson, Graham R., & Prosser, Sue (2002). Action research: Politics, ethics and participation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(5), 587-593.

Zeni, Jane (Ed.) (2001). Ethical issues in practitioner research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Zuber-Skerritt, Ortun, & Fletcher, Margaret (2007). The quality of an action research thesis in social sciences. Quality Assurance in Education, (15)4, 413-436.

Zuber-Skerritt, Ortrun, & Perry, Chad (2002). Action research within organizations and university thesis writing. The Learning Organization, 9(4), 171-179.

Joel MARTÍ is professor of sociology in Autonomous University of Barcelona since 1995. His research interest covers participatory research, discourse analysis, social networks analysis and other topics related to social research methods.

Contact:

Joel Martí

Departament de Sociologia

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Campus UAB – 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain

Tel.: 00 34 93 581 80 21

Fax: 00 34 93 581 28 27

E-mail: Joel.Marti@uab.cat

Martí, Joel (2008). From Local Practices to Public Knowledge: Action Research as Scientific Contribution. Review Essay: Kathryn Herr & Gary L. Anderson (2005). The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty [46 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 2, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs080320.