Volume 7, No. 4, Art. 37 – September 2006

But Does "Ethnography By Any Other Name" Really Promote Real Ethnography?

Wolff-Michael Roth

Abstract: Categorization—such as deciding whether something is real ethnography—is a difficult task, because nature and social practices, the topics of ethnography, themselves do not come with inherent labels. In this article, which takes its starting point in AGAR's contribution to the debate on the quality of qualitative research, I articulate and expose the aporetic and internally contradictory nature of categorizing something as real ethnography.

Key words: ethnography, categorization, identity, difference, chaos and catastrophe theory, boundary work

Table of Contents

1. When is Real Ethnography Really Real?

2. On Boundary Work/Management

3. What is in/behind a Name?

4. Identity and Difference

5. The Conjugations of Position and Reflexivity

6. Toward a Difference Perspective

1. When is Real Ethnography Really Real?

"Carlos Castaneda's interviews with don Juan were initiated while he was a student of anthropology a the University of California, Los Angeles. We are indebted to him for his patience, his courage, and his perspicacity in seeking out and facing the challenge of his dual apprenticeship, and in reporting to us the details of his experiences. In this work he demonstrates the essential skill of good ethnography—the capacity to enter into an alien world." (GOLDSCHMIDT, 1968, p.10, my emphasis)

In the 1960s to 1980s, Carlos CASTANEDA published a series of books that were advertised as constituting ethnographic studies of sorcery in a particular Mexican Indian tribe, the Yaqui; the books include The Teachings of Don Juan, Tales of Power, Journey to Ixtlan, and Second Ring of Power. As my introductory quote shows, the preface of the first of these books suggests to the reader that at least it, published in 1968, "demonstrated the essential skill of good ethnography." In the late 1970s and 1980s, when I read every single one of the books the author had published, I did not know much about anthropology and the ethnographic research method—I had a graduate degree in physics and a future Nobel Prize winner among my instructors. It did not matter to me whether the books constituted real ethnography, that is, "des histoires vraies" (true [hi-]stories), as the French say. The books were a good read (unreal! In the sense of really really good), especially after having smoked a few joints; and I had quite a few at the time and a few good times as well. The interesting aspect of CASTANEDA's work is that after initially going by as ethnographic studies, criticism mounted discounting the work as ethnographic. All of a sudden it was no longer the real ethnography that it had been before. What had happened? [1]

In the foreword to The Power of Silence: Further Lessons of Don Juan CASTANEDA (1987) claims that his "books are a true account of a teaching method that don Juan Matus, a Mexican Indian sorcerer, used in order to help me [CC] understand the sorcerer's world" (p.vii). One may question the truthfulness of the description "true account," but this, I suggest, does not get us far. In my reading, this statement serves certain rhetorical functions directed toward the readers; as an ethnographer, I would be interested how these readers make use of precisely that statement. Thus, my wife likes the ring of a story as being "une histoire vraie" or being "based on true events." In her case, descriptors of an account or story of being true or based on true events—she likes, for example, the crime investigations authored by the University of North Carolina forensic anthropologist Kathy REICHS—have served a particular function, which deserves being studied as a social phenomenon. Thus, CASTANEDA himself qualifies in one of his books the nature of his writings: "although I am an anthropologist, this is not strictly anthropological work; yet it has its roots in cultural anthropology" (CASTANEDA, 1982, p.7). This sentence, too, can be understood in a number of ways, allowing us to understand, depending on our disposition, the work as real or not so real anthropology (ethnography). Does "not strictly" mean the work is over the line, on the other side? Or does it mean still on this side, as it "has its roots in" anthropology? It depends who you are. "Being based on" or "having roots in" can be used as resources for making the decision about inside/outside, in each case legitimately founded in textual analysis. However it may be, one contextual aspect can be ascertained: CASTANEDA did take classes in anthropology at UCLA. What is not so clear is whether he had actually been among the Yaqui, whether there was an informant referred to as "don Juan," or whether CASTANEDA made it all up. Analysts of his work show numerous instances where the details CASTANEDA provides are inaccurate and inconsistent with other studies of the Yaqui, including sorcery practices, geography, flora and fauna, and places. Critics also point out that textual analysis shows the author had "borrowed" some of his materials from other authors. [2]

It is evident that after these analyses had been conducted at least some claim that the books do not constitute (good, real) ethnography, though the author may have been inspired by real ethnographies and life circumstances. But what about the moments before the inaccuracies and the potentially fraudulent nature of the work became public? There were many people who thought that the work constituted good ethnography? Walter GOLDSCHMIDT, professor at UCLA, president of the American Anthropological Association, editor of American Anthropologist (1956–61) and co-editor of Ethos and the Journal for the Society of Psychological Anthropology thought so, at least when he wrote his preface to The Teachings of don Juan. Similarly, Edmund CARPENTER, Carnegie Professor of Anthropology at the University of California at Santa Cruz and one-time colleague and collaborator of Marshall MCLUHAN at the University of Toronto, favorably expressed himself concerning the anthropology contained in The Teachings of Don Juan. [3]

So real (good) ethnography cannot be just in the writing, because otherwise a shift from real to nonreal (unreal?) could not have happened. If these leaders in the field of anthropology cannot distinguish real ethnography from not so real ethnography, how should everyday mortals generally and graduate (education) students in particular be able to make a decision as to the nature of real ethnography? If we shift the discussion to make real ethnography dependent on the fit between the really real and real ethnography, we are in trouble, because we would only get ourselves into the infinite regress associated with discussions of truth. [4]

In this FQS issue, Michael AGAR (2006) presents his take on how to distinguish real ethnography or simply ethnography from what is not ethnography or from what pretends to be ethnography. So why does it matter? Or, when does it matter whether something is to be categorized as ethnography and distinguished from non-ethnography? He, AGAR, proposes a method that combines an iterated recursive abductive (IRA) logic with an articulation of context and meaning deriving from changing points of view (POV). But does the IRA-POV method change or improve our task of distinguishing real ethnography from all other forms of inquiry? Perhaps the question itself is in need of a change in POV, that is, requires us to make a shift from POV1 to POV2, as AGAR recommends. [5]

The question AGAR poses really appears to me undecidable. While reflecting on his essay, the saying some attribute to the baseball umpire Bill KLEM came to my mind: "It's nothing until I call it." For non-baseball fans a brief explanation of the point: the umpire calls a throw a "strike" when the batter at the plate fails to hit it or fouls it out of the field and calls it a "ball" when it does not enter the strike zone and is not struck. Bill KLEM wanted to say that it is useless to argue about a play until he, the umpire, has said "ball" or "strike," which then defines the truth of the situation—it is a little like Erwin SCHRÖDINGER's cat that AGAR invokes, of which we do not know whether it is dead or alive in its cage with a poison-containing vial that is opened upon the decay of a radioactive atom until we actually check. It is the action of checking that makes the undecided situation go one or the other way, renders possibilities into a singularity, just as the umpire's call makes the nature of an undecided and undecidable situation go one or the other way. And thus it is with the question whether something really is real ethnography or not. As long as there were respected scholars calling CASTANEDA's "studies" good anthropological work, it was thus; now that most respected and respectable anthropologists distance themselves from the work, The Teachings of Don Juan no longer constitute real ethnography. [6]

My comment concerning respected and respectable anthropologists leads me to another important point. To be respectable and respected, one needs to be on the inside of the boundary of those who do real ethnography distinguished from those outside and who therefore do not belong to the club. This boundary, as any academic, disciplinary, and national boundary is movable; wars are fought over where precisely the boundary should run—and this question is completely apart from the question to whom the boundary itself belongs. I—though others may differ—read the text as belonging to the wars over such a boundary. More generally, we can read AGAR's text in two ways, and both ways at once: (a) as a text that exposes some of the wrangling that has been going on over what constitutes real ethnography and (b) as another installment of a war over where the boundary between real ethnography and forms of research that only claim to be but are not ethnography. [7]

2. On Boundary Work/Management

There is a tremendous literature on boundary work and boundary management; a quick check of the ISI Web of Knowledge lists over 40 articles just for the period from January to June 2006. The demarcation of some parts of science from other intellectual activities—i.e., non-science, such as creationism—has been a long-standing problem of philosophers and sociologists, at least since Auguste COMTE sought to establish unique and essential characteristics of science that distinguish it from other intellectual activities. He, as others, failed. The continuing debate over the possibility or desirability of demarcating science from nonscience are ironic, wrote Thomas F. GIERYN (1983) over twenty years ago. This is also why I think AGAR ultimately fails, because he, too, attempts to use internal criteria of ethnography—the IRA-POV method—to distinguish real ethnography from other forms of intellectual endeavors that are not real ethnography—such as the book he described to have reviewed about a hospital ethnography where, according to him, the scholar did not know what ethnography was (¶27). The fact it was printed at all shows that it made the peer-review threshold. I hold it with other scholars in the social studies of science—one of my own fields of scholarship—to look at the demarcation in terms of the ideological efforts scientists themselves (e.g., AGAR) mount "to distinguish their work and its products from non-scientific intellectual activities" (GIERYN, 1983, p.782). [8]

Boundary work is a pervasive aspect of and in society. For example, I recently studied a controversy in the small town where I live and in which I studied the role of science and scientific knowledge as it pertained to the preservation of the environment and environmental health (ROTH et al., 2004). The residents in a particular part of our town do not have access to the water grid but rather draw this "life-giving liquid" from wells. However, both because of long and dry summers and because of an increasing pressure on the ground water levels due to irrigation by the farms in the valley, the water levels in the wells decrease during the four summer months to such a degree that the bacterial and chemical contamination levels increase above Canadian drinking water standards. The local health authorities publish a water—boil advisory, meaning that the water cannot be consumed without having been boiled; nothing is done about the chemical contamination, which is considered a mere "aesthetic problem." The residents have to drive five kilometers to the next gas station to get their drinking water—thereby not addressing the corrosion to their appliances and pipes and the destructive impact on their plants, let alone the difficult-to-establish long-term impact on their health. [9]

The easiest would be to extend the currently existing water grid and to hook up this one street. The town politicians, however, do not want to connect the residents to the water grid in order to prevent the development of housing in the area. Although there is substantial housing development in other parts of the town, converting land from agrarian to housing designation, the politicians are adamant not to allow development on this street. They hired scientific consultants and, in the ensuing public debate, the issue is precisely about the question who can legitimately speak for the water issues along the road of interest. The scientists and some of the people involved claim that science has a superior methodology and therefore should have the ultimate say on the pertinent issues. However, it turns out that the local residents discover and articulate faults in the method and claims the scientists made, in part building on their thirty-year familiarity with the area. They claim superiority of their contribution to the debate based on a historical understanding of the water quantity and quality; and they claim superiority based on the fact that they are the victims. [10]

The key point here is that there are particular (partial) interests involved, and these interests mediate where different parties want the boundary to run. The issues do not include common interests or environmental and social justice but rather partial interests, and to pursue these, some parts of society have to be declared as lying just outside the boundaries. Of course, by drawing boundaries both insiders and outsiders recognize their mutual existence. The question is not about the being of the other but rather about the other as being-other, where the other is framed in terms of the negative. It is not non-being that is thereby identified but otherness is defined in terms of the same, that which lies outside of the boundary that surrounds everything within, that is, the same, and everything else that is out, and thereby comes to be different than the same. This is a particular problem that philosophers of difference have amply discussed and decried, but this problematic has yet to find its way into pragmatic everyday discourse. I see the same problem in the way AGAR draws boundaries around what he understands as real ethnography, demarcating its space of possibilities and designating all other possibility spaces as being-other. [11]

With respect to possibilities, this is precisely how I view culture: as an unlimited set of possibilities that I find (always) partially realized in any given ethnographic study of a community. Thus, culture comes to be theorized in a dialectical way, where what I can observe—the practices and artifacts—come to constitute the concrete realizations of some of the possibilities, which, inherently, are possibilities for all members of a particular group. Ethnographers report what I, the reader of the ethnography, may also see, but do not have to see because the possibility space includes other ways of seeing. Coming to understand these possibilities rather than just recording the concretely observable practices and artifacts is precisely what a dialectical approach to ethnography and anthropology is about. Rather than demarcating some forms of study as nonethnographic, the question for me is that pertaining to the degree to which a study is compelling. There are no precise criteria, or perhaps better, there are mutually constitutive criteria, which include the methods used—e.g., length of stay, types of records assembled—and the plausibility of the story; there are also the purposes for a story and its suitability to meet the demands that come with the purposes. These criteria inherently cannot be generalized, as they are to a large extent a question of position and interest: Is the study plausible and useful for the purposes to which it has been constructed? But it should be evident that here, too, boundary work can ensue, because some beneficiaries of (customers who ordered) a hospital ethnography may argue over plausibility and use of the findings. They may draw the proverbial "line in the sand" and then begin their boundary work, which consists in mounting an argument why the line should be where it is. [12]

The question of whether something is compelling—or the instruction to budding ethnographers to write compelling stories—comes down to convincing your (future) colleagues (e.g., in peer review) that they would be able to see the same phenomena and construct the same concepts although you know—as AGAR tells us—ethnographers certainly would see and find something different. This is so because if you, the ethnographer, do not find something different, you are no longer ethnographer, let alone a real ethnographer. There is therefore an inner contradiction in the field whereby you, a member, attempt to convince others claiming to be members that they would see something that they precisely would not want to see because of their professional need to distinguish themselves and assert themselves by seeing and conceptualizing something else. You are an insider as long as you create something new, which is not yet inside, but you are out precisely then when you see (describe) what others (real ethnographers) are seeing (describing). [13]

Focusing on the ideological efforts of scientists themselves will allow us to understand the nature of the boundary work by means of which insiders are distinguished from outsiders. This distinction has pragmatic and political effects, for example, providing insiders with access to financial (governmental) resources while prohibiting others the same access to "the trough." It is precisely as an ethnographer that I understand AGAR's (discursive, textual) actions as boundary work, because I have seen such work while working in national funding agencies such as the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (e.g., ROTH, 2002). The autonomy gained from being on the inside also allows ethnographers (scientists) to gain symbolic resources, such as recognition including awards and (Nobel) prizes and financial compensation and advancement on university salary scales. From this perspective, Michael AGAR is but one of the players who has something at stake, which he defends by outlining where he sees the boundary between the insiders of ethnography and those who do other stuff. And he also writes as a victim of the process, because of the particular work that he has conducted and which other real ethnographers did not want to accept as being on the inside, thereby attempting to do to AGAR what AGAR does to the hospital ethnographer he is writing about (¶27), who, if others follow, thereby becomes a non-ethnographer of a hospital non-ethnography. [14]

Having concepts, notions, and names—e.g., ethnography, real ethnography—and using them without too much reflection, of course, comes with benefits. Being able to say, "I don't know what is going on here, in my institution, I need an ethnographer" allows me to look for someone who fits the bill by quickly sorting through a complex world (e.g., yellow pages, university web page listing consultants, specialists) to get me the service I currently need. If I am interested in finding out how people make sense on the shop floor, it is precisely an ethnographer that I may need, not a monomaniac of linear structural relations or hierarchical linear models. My problem becomes more complex when it comes to making a decision of choosing a person among all those who use the label of ethnography for naming what they do. [15]

When I have to choose within a particular category—e.g., ethnography, real ethnography—each member of which is a constituent moment of the category, I need to do more work to find out whether the person I want to hire can do the job I want to have done. Labels alone do no longer work; certificates, degrees, courses taken, and other descriptors won't do the work either. I actually have to do a little ethnography myself to find out who best fits my bill, the job at hand. In this ethnography, I will inquire about the history of the jobs the applicants have done, perhaps require them to provide portfolios, and do some interviewing. I will no longer rely on claims to be a real ethnographer but gather my own evidence whether what a person does fits my needs. In fact, it may turn out that the person best suited does not at all lay claim to do real or not so real ethnography. And here are some of the reasons why I think in this way. [16]

Many of my European colleagues, but especially those from France and Germany, tell me that my personal career (career trajectory) would have been impossible in their countries. Thus, although they recognize that I have been very successful outside the areas in which I actually have received my graduate training—physics, statistics in the social sciences, applied mathematics, physical chemistry—and have a professorship outside as well, they also tell me that in their countries I could have had a career only inside these areas of training. That is, the name of the discipline I studied would have defined my career, as it would have been used to characterize where along the boundary I would come down: inside or outside. It would have been the discipline name on my diploma that would have made me lie on the inside or outside of a particular boundary, not the form and content of my research. [17]

In the same North American context from which AGAR writes, these same boundaries are actually changeable or play only a minor role—depending on the case at hand. Thus, I do research and publish in fields that are very different from my root disciplines—sociology, linguistics, qualitative research methods, cultural-historical studies—and it is precisely characteristics other than those fixed to my diplomas that have allowed me to be an insider in other disciplines. In this case, if the name (discipline, diploma) had defined my career, I would be somewhere very different (geographically, career-wise, intellectually). [18]

Now it does not matter whether I am a real ethnographer when I spend five years in a fish hatchery to study knowing and learning, following a PhD student in ecology for three years, or spend five years in the same science laboratory. This, too, is why I prefer using descriptions over names or concepts. Ultimately, the writing speaks for itself, and peers can decide whether they find my writing useful or not, whether it is real or unreal ethnography, ethnographic (the designation educators often use to designate studies that in some aspects resemble ethnographies but are not real ethnographies, for example, because the shortness of the researcher's stay prevents and real deep understanding), or not ethnography at all. What matters is whether the accounts I provide of the life in the hatchery, among ecologists, or in the research laboratory generally and of knowing and learning more particularly are compelling, interesting, and plausible. [19]

The debates concerning boundaries and the boundary work itself are premised by or presuppose a particular ontology: identity of the same, self-identity. Difference is the result of saying that something is not the same as something else, the point of reference, which is identical with itself. Boundary work therefore identifies a category, within which everything is the same in one or more ways; everything else is said to be singular because different (DELEUZE, 1968/1994). As DELEUZE shows, this approach is problematic, as difference does not exist in and for itself but depends on the notion of the same (identity) when in fact "all identities are only simulated, produced as an optical 'effect' by the more profound game of difference and repetition" (p.xix). I see Michael AGAR engage in the former game, where he identifies what lies within the category of real ethnography and denotes everything else as lying outside the attractor that constitutes real ethnography. The problem of identification is not resolved by moving away from the naming, "how do you tell that it is real ethnography," by identifying some attractor space. This is so because to lie within the space (surface), there is still something assumed to be the same—e.g., the set of equations defining the dynamic of the system. [20]

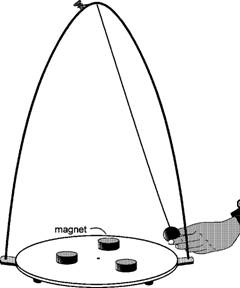

Let us pursue the idea that we are dealing with a complex system that can be described by some dynamics of a chaotic system. Even very simple chaotic systems are highly complex and have multiple not single attractors. And a little chance disturbance can push the system into completely chaotic state where no classification is possible at all. Here are some simple examples. First, even a simple pendulum constructed from three magnets and an iron bob (Figure 1) has three attractors. Given the "same" conditions and beginning with the "same" starting point, there are three possible outcomes and it cannot be predicted where the bob will end up—which differs from AGAR's claim that there might be something that would define successful trajectories pulling an ethnography into the space of the real ethnography. That is, we do not know whether a trajectory lies within the space of one (e.g., real ethnography) rather than another attractor (unreal, non real ethnography). In the case of the pendulum, there is not even a way of deciding where the pendulum is going to end up right to the very end, as the trajectory itself is unpredictable, allowing the bob to be caught in one or the other attractor.

Figure 1: The magnetic pendulum has three rather than one attractor so that it cannot be predicted where the bob will end

even when the same starting point is chosen over and over again and when the conditions are held constant. [21]

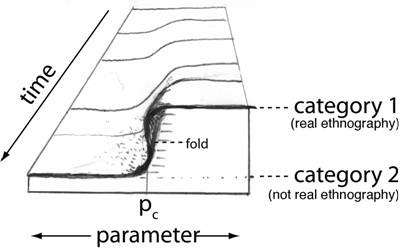

To take another example from my research on classification, where I used the forerunner to chaos theory, catastrophe theory, to model precisely the difficult cases for deciding whether some entity belongs into one or the other category. Here, I am not interested in the easy cases—a linear structural analysis employing LISREL, LISPL, or EQS clearly is not ethnography. I am interested in the hard and limit cases, which question the very categorization itself. Thus, given certain conditions, scientists learn to make distinctions in the field of interest between two types of instances, categories 1 and 2, such as identifying something as real ethnography and something else as not real ethnography, only pretending to be ethnography. As Figure 2 shows, once such a distinction has been established, which itself is the outcome of a cultural historical process, then there still exists a fold around parameter pc where something could be one or the other.

Figure 2: Catastrophe theory can be used to describe how some entity will be classified according to one or the other categorization.

Whereas this may be easy in many cases, those that lie near the "fold" in the foreground unpredictably change from one to

the other state. [22]

Inherently and ontologically, the true state of the something in the region of the fold is undecidable, just as the question whether the proverbial cat of Erwin SCHRÖDINGER is alive or not. The thing can be either one and depending on the input provided, we find it in one or the other category. Pragmatically, of course, we may decide that something is real ethnography (category 1 in Figure 2). But it could be otherwise as well (unreal or not-so-real ethnography [category 2 in Figure 2]). So taking a book as featuring real ethnography does not mean it really is real ethnography, because it could be otherwise as well. This precisely is been my point above when I refer to AGAR's example with the hospital ethnography that he, Michael AGAR, decided was not a real ethnography. [23]

The situations I describe here are simple compared to the question whether something is real ethnography. My tendency would be to spend our time elsewhere rather than on establishing general criteria and discussing cases to find out on which side some study comes down and to spend more time on cases where it matters for making (interest-laden) decisions that matter to the situation at hand. As I show in the case of the discussions in funding councils concerning the quality of research, these decision cannot be predicted even if the same set of statements enter the modeling equation, because minor influences can make a decision go to "not-fund the project" instead of to "fund the project" because it is the real thing whereas the former is not (ROTH, 2002, Figure 1, ¶59). My modeling exercise and the diagrams that come with it show that even minor changes—e.g., the temporal organization of attributions made about a given study—can change the decision about a study as fundable or non-fundable. My sense is that we need to begin differently, namely in acknowledging difference as the starting point and then study how "identities are …. simulated, produced as an 'optical effect'" (DELEUZE, 1968/1994, p.xix). This question is precisely the one that interests me most in AGAR's article, namely what he does to create an optical effect by means of which some things come to be the same, denoted by the term "real ethnography" and how other things fall outside. [24]

The interesting aspect of the analogy in Figure 2 lies at the fold, because it is precisely here that we find those characteristics of a system most closely related to human nature: change of structure. It is precisely here—where in mathematical analogies we find singularities—that unpredictability emerges. Now, concepts, as we see in Section 3, are useful because they allow us to rapidly deal with the complexities of life. But they only allow us predictability up to a certain point. We do know that at the very foundation, life is unpredictable—we would not engage in games and Olympiads if we knew the outcome beforehand, we would not have to have tenure and promotion meetings to discuss a case if we knew the decision in advance, and we would not marry if we knew that some time down the road we would have to go through an acrimonious and costly divorce. Singularities mean inherent difference, unavoidable, for all times; sameness and identity are constructed; they are but optical effects. From this perspective, therefore, identity means work, the work of making something be the same despite all the obvious differences that candidate objects for a category; and this is precisely the kind of work which we have come to know under the denotation of boundary work, they kind of stuff ethnography is made for to research and write about. [25]

5. The Conjugations of Position and Reflexivity

Michael AGAR proposes an interesting concept, which he does not develop to its fullest, which he cannot develop to the fullest if we buy into the notion of semiosis as an unlimited process, but which is one that I personally am particularly interested in. It is the play on the notion of point of view, which comes from the singularity of the position that we necessarily take because of our material bodies. The spatio-temporal position we take/occupy cannot be taken/occupied by anyone else—a fundamental realization in the epistemology of physics. Two or more material things cannot take up one and the same position in space-time. Taking up a point in space-time therefore constitutes a singularity, and this singularity comes with a particular perspective, as the following conjugation of the term position with various prepositions shows. [26]

The notion of position can be conjugated with a number of prepositions, which then allows us to take a reflexive stance with respect to what makes our own position possible: suppositions, presuppositions, and dispositions all come with a position, all marking out the rather singular nature of our being in its entirety, our understandings, and our POVs. Even and especially the notion of preposition allows us to see that prior to our position we already take position, a form of relation, a position before any position has been taken (consciously), a beginning before the beginning, or, in the words of Emmanuel LEVINAS (1998), "otherwise than being" and from "beyond essence." As material entities, we are pre-positioned before we can consciously take position on something; and with the preposition come the presuppositions and (hidden, apparent) suppositions and dispositions. In fact, the notion of disposition can be heard not only in its common sense as denoting mood, temperament, and habitual tendency but also as distribution and arrangement, which inherently means difference. Disposition is different position, inherently relative to other positions, therefore pre-positioned, and different position is different point of view and habitual tendency of seeing and understanding. This holds for Michael AGAR—whose text does not actively acknowledge it, for whatever reasons—and myself: and I do recognize the singularity that comes with my position, leading to particular dispositions, presuppositions, and suppositions. If this is the case, then neither he nor I do have a privileged POV, which relativizes his advice for distinguishing real ethnography from other form of intellectual activity and his advice to others what to do to distinguish themselves from impostors. [27]

This conjugation is more than an exercise. Other interesting stuff and realizations derive from further conjugations. For example, imposition constitutes the action of attaching, affixing, or ascribing a name to someone else. Is this not what AGAR does by naming some things real ethnography and denying the same name to other things? More so, this conjugation alerts us to the fact that the imposition has come from a position, itself associated with presuppositions. The imposition was stated as a proposition, which, too, inherently is associated with suppositions and presuppositions. By stating the imposition in the form of a proposition, AGAR put out something to public view, and this action constitutes an exposition. [28]

6. Toward a Difference Perspective

To return to my beginning story, I raise the question again: Do CASTANEDA's books constitute good (real) ethnography? Well, it depends. They constitute a good read, especially if you are stoned. Precisely then can you see that there is something at least metaphorical and allegorical about the content of these books. When you are stoned, you can have precisely some of the experiences that CASTANEDA describes in the book about sorcery. I know of individuals who, after ingesting peyote, have seen the dog CASTANEDA describes to have seen after ingesting peyote or that he describes his main protagonist—an ethnographer called by the same name Carlos CASTANEDA—to have seen after ingesting peyote. (On the strategy of distinguishing the author of an ethnography from the protagonist in the ethnographic story bearing the same name, see my critique of The Sneaky Kid, Harry WOLCOTT's autobiographic ethnography about his homosexual relation with a research participant [ROTH, 2004]. On the same strategy also see Jacques DERRIDA [2006] discussing the work of the French author, novelist, poetess, and literary scholar Hélène CIXOUS.) [29]

The answer would certainly be different or more differentiated if I were an ethnographer or anthropologist concerned with understanding the ways of the Yaqui generally and of Yaqui sorcerers in particular. As is my habit, I would not stop with one account but seek other reports, allowing me to appreciate what authors with different positions, dispositions, predispositions, suppositions, presuppositions, propositions, expositions, and prepositions articulate about the tribe. I do the same when I read medical research studies, making up my mind about the suitability of causal attributions and discourse. In many instances, medical research uses correlational research but makes causal claims about the consequences of eating this or that, drinking alcohol, or smoking. Yet in the very scientific paradigm that the medical researchers are working in, they ought not make causal claims unless certain procedures have been followed that unequivocally allow the causal association between one factor and another one. [30]

So, rather than thinking in terms of real and not-so-real (unreal, non-) ethnography, I think in terms of the plausibility and in terms of the degree to which a narrative is compelling. Thus, although many readers found WOLCOTT's (2002) writings concerning the Sneaky Kid real ethnography, I found it not compelling at all and highly questionable on ethical grounds. On the other hand, I found Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung Woman (SHOSTAK, 1983) to be highly interesting, compelling, and informative even though the ethnographer inserted herself very little into Nisa's narrative, writing in her voice only at the chapter beginnings. Is it real ethnography? Some in the field of anthropology do not appear to think so, even though others including the author herself, consider the book to be a major corrective to previous anthropological accounts (e.g., MARCUS & FISCHER, 1986). But I also find Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis (ROSALDO, 1989) very compelling, even though it constitutes a very different genre, mixing life stories, ethnographic reports, and texts about anthropological method. [31]

To return to the AGAR text itself, my recommendation to readers is to make up their own minds. I caution to be aware of finding in it a panacea for deciding between real ethnography and other intellectual pursuits and a method for learning to do real ethnography versus doing other forms of research. There are no panaceas for dealing with the complexity of life and I personally am suspicious of anyone who claims to provide a simple model. The IRA-POV formula solves as few problems and provides as few answers to the really interesting and hard questions of doing ethnography that the left brain/right brain distinction does for understanding learning, or that the personality type-A/type-B distinction does for understanding the differences between people. [32]

Ultimately, then, I find it easy to live with this motto: We are different because we are singular rather than being singular because different (from the same). In this way, I do not have to do work to prove that (in each case) you are different, because this is the starting point. The question then becomes one of deciding what we have to do to collaborate, get along, or avoid conflict in the face of the irremediable and ontologically grounded difference. The questions include: To what degree are we the same (ethnographers)? What is the degree of overlap between what you do and what I do (ethnography)? [33]

Agar, Michael (2006). An ethnography by any other name … [149 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 36. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/4-06/06-4-36-e.htm [Date of Access: August 22, 2006].

Castaneda, Carlos (1968). The teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui way of knowledge. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Castaneda, Carlos (1982). The eagle's gift. New York: Penguin Books.

Castaneda, Carlos (1987). The power of silence: Further lessons of don Juan. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Deleuze, Gilles (1994). Repetition and difference (P. Patton, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press. (First published in 1968)

Derrida, Jacques (2006). H.C. for life. That is to say. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gieryn, Thomas F. (1983). Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: Strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review, 48, 781-795.

Goldschmidt, Walter (1968). Foreword. In Carlos Castaneda, The teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui way of knowledge (pp.9-10). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Levinas, Emmanuel (1998). Otherwise than being or beyond essence (A. Lingis, transl.). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Marcus, George E., & Fischer, Michael M.J. (1986). Anthropology as a cultural critique: An experimental moment in the human sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rosaldo, Renato (1989). Culture & truth: The remaking of social analysis. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2002). Evaluation and adjudication of research proposals: Vagaries and politics of funding (92 paragraphs). Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(4), Art. 25. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-02/3-02roth-e.htm [Date of Access: August 22, 2006].

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004). Autobiography as scientific text: A dialectical approach to the role of experience. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(1), Art. 9. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-04/1-04review-roth-e.htm [Date of Access: August 22, 2006].

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Riecken, Janet; Pozzer, Lilian L.; McMillan, Robin; Storr, Brenda; Tait, Donna; Bradshaw, Gail, & Pauluth Penner, Trudy (2004). Those who get hurt aren't always being heard: Scientist-resident interactions over community water. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 29(2), 153-183.

Shostak, Marjorie (1983). Nisa: The life and words of a !Kung woman. New York: Random House.

Wolcott, Harry F. (2002). Sneaky kid and its aftermath: Ethics and intimacy in fieldwork. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira.

Wolff-Michael ROTH is Lansdowne Professor of applied cognitive science at the University of Victoria. His interdisciplinary research agenda includes studies in science and mathematics education, general education, applied cognitive science, sociology of science, and linguistics (pragmatics). His recent publications include Talking Science: Language and Learning in Science (Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), Doing Qualitative Research: Praxis of Method (SensePublishers, 2005), and Learning Science: A Singular Plural Perspective (SensePublishers, 2006).

Contact:

Wolff-Michael Roth

Lansdowne Professor

MacLaurin Building A548

University of Victoria, BC, V8W 3N4

Canada

E-mail: mroth@uvic.ca

URL: http://www.educ.uvic.ca/faculty/mroth/

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2006). But Does "Ethnography By Any Other Name" Really Promote Real Ethnography? [33 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 37, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0604374.