Volume 7, No. 4, Art. 22 – September 2006

Responsibility and Coteaching: A Review of "Warts and All"

Ian Stith

Abstract: Coteaching, like any student teaching method, is filled with ethical questions and communicative problems. With the metalogue presented in "Warts and all: Ethical dilemmas in implementing the coteaching model" as the base this paper focuses on the experience of Matt, the student teacher, and the ethically issues he faced as a coteacher. In line with the experiences of Matt I reanalyze the question of how change can be implemented given the variety of philosophies of education inherent in a large-scale project. Finally, the cogenerative dialogue is presented as an ethical tool to increase the quality and frequency of communication between participants.

Key words: ethics, coteaching, cogenerative dialogue, responsibility

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 The activity system and the ethics of responsibility

2. Another Look at the Metalogue

2.1 "My student teacher" and coplanning

2.2 The voice of the participants

2.3 The role of researcher

2.4 Difference in philosophy of education

2.5 The cogenerative dialogue

3. Coda

Student teaching is a strange and complicated activity nearly all teachers in the United States go through as part of their training. It is something they will never do again and is an activity that has dramatic differences from the activity it is meant to replicate. The student teaching experience of pre-service teachers vary greatly across the country but most follow the familiar structure of one cooperating teacher working with one student teacher who gradually takes complete control of the class. Contrary to this model is the coteaching approach, which can be described as "teaching at the elbow of another" (ROTH & TOBIN, 2002). Coteaching is fundamentally different from other methods in that it focuses on equity between coteaching partners. As opposed to a hierarchical concept of knowledge transfer the coteaching model encourages teamwork and mutual learning between the student teacher and cooperating teacher. In addition the coteaching model exists dialectically with the cogenerative dialogue, which is a meeting of students, teachers, supervisors, researchers, etc. to discuss the events of the day and plan for the future (ROTH, LAWLESS & TOBIN, 2000; TOBIN, ZURBANO, FORD, & CARAMBO, 2003). The relationship between cogenerative dialogue and coteaching is one of mutual dependence and is a topic of discussion later in this paper. [1]

In the context of "Warts and All: Ethical Dilemmas in Implementing the Coteaching Model" GALLO-FOX, WASSELL, SCANTLEBURY, and JUCK (2006) discuss the implementation of the coteaching model into the teacher education program headed by Kate SCANTLEBURY. From the metalogue the article contains, we learn about the ethical challenges the participants faced throughout the coteaching experience, while researching the coteaching experience, and in the discussions of the findings. In these three contexts there is the overarching ethical concern of inclusion of participant voice along with the general ethical concerns with regard to the role of the researcher in the activity. In line with the commitment to include the voice of the participants, GALLO-FOX et al. include a metalogue as opposed to a single voice to discuss the research project. It is my intention here to analyze this metalogue and the project it describes in terms of the ethics of responsibility as an activity system. [2]

1.1 The activity system and the ethics of responsibility

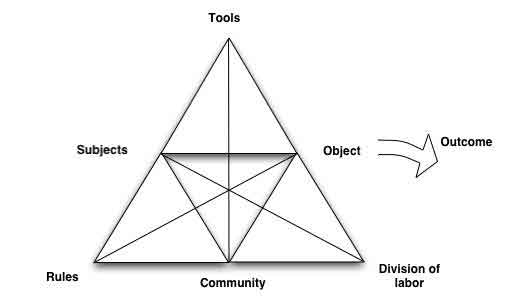

Using cultural-historical activity theory (ENGESTRÖM, 1993; LEONT'EV, 1978, 1981) as a theoretical framework allows us to analyze the student teaching experience of Matt as the truly complex social system that it is. Cultural-historical activity theory allows us to frame the participants in a given activity as subjects with a particular object of intention. The actions of the subjects are mediated by the tools, the division of labor, the community, and the rules associated with the particular activity (Figure 1). In the case of coteaching in general we have the student teacher, the cooperating teacher, the supervisor, and so on as subjects whose actions are mediated, for example, by the division of labor between the student teacher and the cooperating teacher. In the particular case of Matt's coteaching activity discussed below, we see his interactions as mediated by his respect for Rosie (the cooperating teacher) as a teacher. Activity theory is of particular use to me for this discussion because of the focus on ethics and the concept of responsibility.

Figure 1: The basic cultural-history activity triangle [3]

Responsibility can be used various ways, but I will use it both in reference to the act and more generally in reference to our own sense of "self." In line with activity theory I analyze the actions of individuals in reference to the activity they act within; but to take this a step further I must analyze these acts in terms of ethics. In any given activity, acts begin with intention and conclude with completion. In terms of responsibility the person who completes the act is responsible for the outcome of the action just as the person who intentionally performed it (BAKHTIN, 1993). I also will rely on the ethical basis of being as inherently being singular plural (NANCY, 2000). In other words, we have a responsibility toward others that populate the world because we are constitutive of their being (LEVINAS, 1998). Our own being-in-the-world already includes other beings in the world—self and other, subjectivity and intersubjectivity, self and world all emerge at the same moment: being inherently is being singular plural. Responsibility is not given or taken: it rather exists beyond being, "prior to every memory," and without it being would be impossible (LEVINAS, 1998). Responsibility is continuous; it has existed before one's awareness and will continue after death. We cannot relate to others without our own sense of being, which in turn is dependent on others, thus constituting the dialectics of self and the other—oneself always also is another to another self (RICŒUR, 1992). [4]

2. Another Look at the Metalogue

The following focuses on Matt, the student teacher, or intern, and his own descriptions of what occurred throughout his coteaching experience. From his descriptions in the metalogue I build a concept of what his experience was really like and begin to understand how those around him mediated his own learning. Also, I will refer to the question by GALLO-FOX et al. (2006, ¶1): "How can one advocate new approaches to teaching and teaching education and simultaneously work productively with people in the field who have different philosophical perspectives?" [5]

2.1 "My student teacher" and coplanning

The following is a quote from Matt concerning his relationship with Rosie, one of his cooperating teachers. Here Matt analyzes the way he was regarded and referred to by Rosie and how this clashed with his own concept of what his coteaching experience was and what coteaching theoretically was intended to do. Matt points out the way Rosie addressed him as "my student teacher" instead of as a coteacher or even intern, as he would have preferred. With regard to the manner with which their actions are mediated by the division of labor associated with student teaching this point is of particularly importance. Coteaching in general emphasizes an equality and cooperation between the coteachers that is in opposition to the concept of teacher and student teacher with the associated expectations. Rosie, here, is involved in the coteaching model by working with one of Kate's students but has not applied the theoretical basis to her own interactions and speech. The idea that she "owns" Matt implies a subordination and separation between the participants contrary to the goals of coteaching. In addition to the divisive nature of this stance by Rosie on a personal level between her and Matt it also implies an expertise and finality to the teacher education process. Student teachers are simply beginning the continuing process of learning to teach and as such even Rosie is learning and changing while working with Matt. In fact it is extremely likely that Rosie is learning from Matt and so they learn to teach together, just as coteaching implies. Rosie, by addressing Matt as someone who is lacking the knowledge she processes, is taking a deficit view that only reinforces the isolation that most teachers feel (TILLMAN, 2003). Again, using activity theory to frame our discussion, we can see how coteaching mandates a manipulation of the division of labor some people reference and so can lead to conflict.

"Matt: 'My student teachers', was a phrase I recall Rosie applying to me and the other interns. This phrase conveyed a sense that she had some form of ownership of the interns in her classroom. In response, I remember thinking that she wasn't the only teacher with whom I was coteaching. Before starting student teaching, I had become accustomed to perceiving myself, and my fellow student teachers, as interns. Personally, I felt that the term portrayed us as more than just students learning how to teach. Clearly, the latter was exactly what this experience was intended to do. I believe that coteaching allowed me to better hone the techniques and methods I will use as a beginning teacher by sharing the responsibilities and decision making of each course with my coteachers. Most importantly, the coteaching environment provided the opportunity for reflection on my teaching practice. [14]" [6]

Continuing from the previous comment Matt goes on to explain how coplanning was conducted by Rosie and how the traditional division of labor associated with student teaching mediated the activity. Instead of Rosie and Matt sitting together as equals and working together to create a lesson plan for them Rosie assumed her role as leader and director of Matt's experience. Again the division of labor associated with this activity is contrary to that associated with a form of coteaching within which the roles would be more equal. In regard to the coteaching model that Kate attempted to introduce this separation is particularly counterproductive for Matt, as he is not given the opportunity to fully engage in the coteaching model and take advantage of the associated benefits. Also Matt cannot participate in discussions of coplanning and coteaching during Kate's seminar classes as completely as he could if his coteaching experience had been more authentic. Ethically, there is also a question here because of the associated responsibility for the outcome of the activity. Despite the approach by Rosie to control the lesson plan and so Matt's actions when actually teaching the outcome is really dependant one what they, along with the students, actually do. If we analyze the activity described by Matt, Rosie handing him the lesson plan as an example we see the responsibility they each have to the completion of the this act and the activity. In this example Rosie initiates the action by handing the lesson plan to Matt; and so she has begun the action and has responsibility for whatever outcome ensues. Matt here has a choice, he could take the lesson plan from her and use it as his own lesson plan, or he could take the lesson plan and disregard it, or he could even refuse to take the plan from Rosie at all. Of course there are countless responses Matt could take, all of which he would be responsible for, he has engaged with Rosie in the action she initiated and completed it in some manner. In the actual case it seems Matt responded in the manner expected by Rosie, to take the lesson plan and apply it appropriately, but regardless of how the action was completed they are both responsible for completing it.

"At times I felt as though Rosie was taking charge of the coplanning sessions and also directing the way a lesson would be taught. For example, during one of our course units, she came to our planning sessions with a written copy of how the material of the unit would be divided up over the course of each week. As I reflect on this I realize that we were not collaboratively planning the unit, but rather that the planning was being directed by one person—our cooperating teacher. " (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶14) [7]

Looking back over the story told by Matt, it is clear that neither he nor Rosie recognized Matt's role in the development of the lesson plan, his responsibility for the outcome of the lesson planning session, and for the outcome of the actual lessons. I do not want to speculate as to why Rosie chose to prepare the unit plan without Matt's input; rather I want to analyze the activity of student teaching, or in this case coplanning. In line with this strictly ethical analysis we again return to coplanning as an activity system and see how Matt's involvement is mandatory. The coplanning session is designed to be a chance for the coteachers to together decide on a lesson plan; in terms of cultural activity theory, both teachers are the subjects of the activity, with the object being the lesson plan. The actions are therefore mediated by their own personal relationship, and other factors, but more importantly, regardless of their relationship, they both determine the outcome of the activity. This concept is central to the idea of coteaching and so it is clear that Matt did not experience coteaching as it was originally conceived. The general ignorance of Matt as a subject in the activity is clear from his description, but also in the more minor details. Matt describes the planning session as a separate activity from his normal interaction with Rosie. Matt says Rosie came to the coplanning session as if she was away and the meeting was a scheduled event, which could be interpreted many ways. With regard to Rosie and Matt's interactions it seems there was little room for casual and immediate feedback or planning for different lessons, which again implies an unnecessary formality to the coteaching experience. Part of coteaching as I understand and experienced it is the idea that everything is done together, not that each decision is communal but rather that the teachers openly discuss issues before, during, and after class. The picture Matt paints here is of an obligatory coplanning meeting conducted not out of desire but rather to satisfy a requirement. Along with this formality we see a continuing commitment to the traditional division of labor and one-way knowledge transfer. [8]

2.2 The voice of the participants

In paragraph 16 reflects on his own lack of voice while working with Rosie and how it may have affected his own, as well as the students, learning.

"I'm not sure why I didn't raise my concerns with Rosie. I assume that part of my decision not to challenge her suggestions was because I respected her as both my cooperating teacher and a teacher. However, my lack of voice in this situation did not allow for my opinions to be acknowledged, and decreased my share of responsibility for the lessons being planned. Thus, the question still remains: did my silence inhibit learning opportunities for everyone partaking in the teaching of the course? Clearly, there was a lack of communication between my fellow interns, Rosie, and myself during certain planning sessions. (Matt, Coteaching Journal, Spring 2004)." (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶16) [9]

Missing from this reflection is the role his supervisor, Sheila, in his learning and his communication with Rosie and so her responsibility as a participant. Matt later goes on to describe his displeasure with Sheila's evaluation technique but he does not discuss Sheila's role both as his connection with Kate and facilitator with Rosie. Sheila's role here is a complicated one and I would claim the roles exist dialectically. Sheila must on the one hand evaluate Matt as a student and pass this information on to Kate, as well as inform Kate of the general state of Matt's experience, and also work with Matt to develop as a teacher. From the article it seems the connection Sheila served between Kate and the student teachers was vital but initially unrecognized, as evident from Kate (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶34). As Matt states at the end of paragraph there was clearly a lack of communication, but this flaw seems to have been more widespread than just between the interns and Rosie. Again if we frame Matt's student teaching experience as an activity system, we can see how the subjects' communication was complicated by the mediating factors in such a manner as to cause conflict. For example, Matt describes his own lack of voice but also states that he did not take the chance to challenge Rosie's method of coplanning. The reason Matt gives for the lack of challenge has to do with respect, which is of course a very weighted term, but regardless there did exist a conflict between Matt and Rosie. [10]

It is interesting how here "sole responsibility" is assigned to Kate for administrating and teaching the entire program. While it may be true that she taught the courses and coordinated the participants the responsibility for the outcome of the program really lays within all the people involved.

"Narrator: As coordinator of the science teaching education program, Kate had sole responsibility for the administration and teaching requirements for the secondary science education program. She introduced coteaching as the model for student teaching. Kate and Pam cotaught the university science methods course. Pam offered her school, Biden High School, as a coteaching site. Pam and Kate met with Biden High's administrators and science faculty to explain coteaching and to recruit cooperating teachers. Several science teachers volunteered in part, because coteaching allowed them to retain responsibility for their classes. In the more traditional student teaching model, over a fifteen-week practicum, cooperating teachers gradually relinquished their teaching responsibilities for a majority of their classes to a student teacher." (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶8) [11]

If we look at the program as an activity system composed of countless layers of connected activities we must acknowledge the role each person plays. Kate may have initiated the infusion of coteaching into the program; but who actually makes it work depends not only on her actions but also those of the students, teachers, interns, supervisors, etc. Kate admits later that she underestimated the role of the supervisors in the successful implementation of the coteaching and the research conducted alongside it. Again, it seems there is a lack of communication between parties involved. Kate mentions she gathered volunteers from the school to be coteacher but this did not guarantee a commitment to the coteaching model. I would think this to be not a question of different philosophies of teaching but rather a lack of clear goals and regular communication as evident from the statement that "She (Pam) admitted that because the interns had not assumed co-responsibility, she intentionally was not coteaching with them" (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶13). This does not sound as if there is a particular resistance to coteaching as a teacher education model but rather a lack of resources and opportunity for the teacher and intern to discuss what is going on. Framed as an activity system it is clear that there is conflict as to how participants' actions are mediated; but I question, how does a "philosophy of teaching" mediate action? And if in fact a "philosophy of education" does mediate action is it malleable or is it assumed to be constant? [12]

2.4 Difference in philosophy of education

As stated before one potential conflict appears to have existed given the division of labor associated with the activity; but in addition is there simply a difference in "philosophy of education"? As stated earlier, a major concern for GALLO-FOX et al. was how change can really happen given the variety of philosophies and the ethical implication of this attempted change. The ethical issues raised by GALLO-FOX et al. revolve, again, around participant voice and the role of the researcher, but do these issues really address the apparent difference of philosophies? The first question I would raise in regard to this difference is, how is this difference of philosophy known and what are the indicators of the difference? Throughout the article there is reference to actions by the participants that seem to conflict with the stated goals of coteaching. But does this necessarily imply a difference of philosophy of education? I would argue that—although it is likely given the narratives presented—we cannot be sure that the apparent conflicts are the direct cause of a difference of philosophy. In addition I would suggest that despite an acknowledged difference of philosophy change is possible and can be ethically achieved. [13]

Despite the stated goal of inclusion of voice by GALLO-FOX et al. there are a few conspicuously missing narrations that would address some of the stated ethical dilemmas. I would begin with Sheila, Matt's supervisor, and then move to Matt's other direct contact for his student teaching experience, Rosie. Both of these individuals are described as having conflicting philosophies with those of coteaching; but how does this really affect their performance? In the case of Sheila we are unable to hear her reasons for certain actions that seem to contradict Kate's intentions. Matt describes his disagreement with her evaluation methods for his teaching, for example, but what we do not see is why these methods were used or if they were made a topic of discussion between the participants. Most importantly here were the lack of communication and the lack of self-understanding the participants had in relation to their roles. Sheila is acknowledge to be a vital link between Matt and Kate (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶5) and yet Kate does not use this to her advantage, instead she is ethically conflicted with regard to whether she should get involved with the research and evaluation of the project and how to inform the work of Sheila. In paragraph 18 we do get a vague description of how problems did evolve over time between Sheila and Kate but we don't see how they were, if at all, resolved. It is clear that Sheila was unenthusiastic about the introduction of the coteaching model but in the end she needed to understand her own responsibility for the outcome of the activity and reevaluate her concept of what her working environment would be. It seems that the question here of how to make change despite differences in philosophy is a rhetorical one; no matter what the activity is, each individual will have his or her own opinion about what "should" be done. Despite any surface agreement there are countless interpretations of what is expected of each person. In this case in particular Sheila apparently felt her role was that of an expert and critic of Matt's classroom management, which, of course, perhaps could be part of the coteaching model, if administered differently. For example, as the coordinator of the entire project, Kate would not want topic of classroom management to be completely ignored but rather may expect it to be discussed in a different manner than Sheila. This is the point GALLO-FOX et al. make; but where I disagree is with manner in which this difference is addressed. Whatever philosophical differences existed between Kate and Sheila are not static entities to be worked around, but rather are continuously developed and redefined. Coteaching was once a new term for Kate, just as it is now for Sheila. The challenge here is not to work around Sheila as a roadblock but rather to incorporate her into the process and keep her opinions as valid. Change within a system will not occur without initiation and contradiction and so these disagreements should be looked at as positives and not obstacles. [14]

Rosie, as Sheila, has much said about her but is not involved in the metalogue and so much is left to inference. Rosie and Matt seem to have been working in a more traditional style of student teaching rather than the coteaching model Kate had designed. But why did this happen? Is it because Rosie refused to deviate from her philosophical stance or are there more complex distributed reasons? As previously discussed Rosie's daily form of communication with the university's teacher education program at large was via Matt and Sheila, and this apparently led to issues, some of which have already been addressed. But we are not privy to Rosie's interpretations of what occurred. Ethically, Rosie is as much as others responsible for what occurred in the class and with the project as a whole; but I would assume she did not see her role in the project as integral. Again, it comes back to the communication between the participants in the activity system of the program. Rosie voluntarily joined the project, but we cannot be sure what she expected or if she understood what was expected of her. The student teacher (Matt) is again torn in multiple directions: on the one hand wanting to do what Kate has told him to and at the same time getting along with Rosie. Rosie really seems to have had very little instruction as to how to coteach with Matt and so it was a learning process for her as well. It is a lot to ask of a teacher to work with an intern and it is even more to ask them to move out of their comfort zone. As addressed below communication and self-understanding needed to be developed among the participants and clearly this was not happening. So in the end coteaching could not really take place. [15]

Matt's previous comment is particularly salient given the intended coteaching model for his student teaching experience and the need for quality debriefing sessions:

"Matt: To build on Kate's comments, the supervisors did represent a critical eye. As interns we, needed to recognize that not everyone would accept coteaching as an effective way to learn how to teach. It is a good experience to have that criticism. It was just hard for me personally, because my supervisor never really supported coteaching and I could tell. I felt disconnected when we would meet for our debriefing after Sheila would observe one of my lessons. I do feel that Sheila provided insightful feedback. Typically, she would review the lesson using the standardized observation form in a stepwise manner. It just seemed that the majority of points she noted were aspects concerning classroom management, such as movement about the room, intonation of voice, etc. I still feel that these were important aspects of the lessons, but I was also looking for some feedback about my teaching. Did my students get the lesson? Were my methods effective or correct? I felt completely confident answering these questions myself, and was getting feedback from each of my cooperating teachers, but I was also looking for that outside approval. Sheila acknowledged that Kate and Pam had decided to use the model before they spoke with her. Thus, the possibility for a disconnection between her ideas and the model exists, as well as between her practices and those participating in the cotaught classrooms: interns, cooperating teachers, and professionals." (GALLO-FOX et al., ¶24) [16]

When Wolff-Michael ROTH and Ken TOBIN formalized coteaching, a similar concern also came to be a point of interest (ROTH, TOBIN, & ZIMMERMAN, 2002). Naturally at first and then more formally, ROTH and TOBIN developed the cogenerative dialogue as a dialectic pair with coteaching. The cogenerative dialogue was developed precisely for the reasons Matt describes as challenges in the cited paragraph, lack of communication between participants and his own lack of voice, to name but a few. Specifically the cogenerative dialogue situates the coteachers, the supervisor, a few students, and possibly other such as researchers, or administrators, together to discuss the events that took place during the given lesson. The cogenerative dialogue is a necessary pair to coteaching for multiple reasons, all of which result in a more ethical and authentic teaching and learning experience for the participants and in a more ethical approach to the research associated with it. [17]

To begin with, the lack of the cogenerative dialogue in this case is particularly of concern with regard to the experience of Matt and his missed opportunity truly to be a coteacher. The cogenerative dialogue encourages equity among the participants and open discussion of whatever issues are important to the participants. For example, Matt and Rosie would have been able to discuss their coplanning sessions or the events that took place during regular class time. Instead of Matt's concerns going unaddressed and unresolved the cogenerative dialogue would have allowed them to work towards an outcome they both could agree with. Ethically, again, there is major concern with the lack of responsibility attributed to the Matt and the other participants that could have been addressed by the cogenerative dialogue. As the goal of the cogenerative dialogue is the formation of an actionable plan, there is implied a responsibility for all those involved for that plan. Responsibility is made a topic of discussion and explored in various ways throughout the discussion. In the case of the coplanning sessions, if these could be discussed and the concept of responsibility for the enacted lessons be explored, then coplanning could take the form as intended by coteaching. The requirement to reach agreement on an action plan forces discussion of points of conflict and suggests mediation. [18]

Matt here is not given the chance to reflect on the daily events of the class with his coteacher. But in addition, he appears to have missed the chance to reflect with the students in his class. Matt comments that he has had issues with the way Sheila evaluated his teaching and makes a specific point concerning his interest in if the "students got the lesson" or not. Matt seems to be looking for Sheila here for feedback rather that to the students directly. Sheila neither provides her opinion on this matter nor does she advise Matt as to how to talk with the students about his questions. Rosie, also, does not advise Matt to do this; rather, she provides Matt with lessons she has already designed. The cogenerative dialogue again is a valuable and necessary tool for Matt to begin to understand the experience of the student. Even though it seems as if Rosie and Sheila disagreed with the coteaching model, they still could have advised Matt to talk with the students about his concerns. In the end, just as Matt and Rosie are both responsible for the outcome of the class, so too are the students and therefore they must be involved with the decisions made for the class. [19]

Finally the cogenerative dialogue provides a valuable time for Matt to talk with Rosie about her own teaching and teaching in general. Matt is an intern to learn about teaching and work with Rosie and the cogenerative dialogue is an ideal setting for him to hear why Rosie makes certain decisions during class or how she came to use certain activities. Watching Rosie work and having her provide lesson plans for him is not enough. To really learn from Rosie, Matt needs to have the opportunity to talk with her about things that actually happened in class. Also, Matt is able to learn about teaching as a profession with all the details left out of teacher training, such as when and how Rosie does her assessments or how to interpret absenteeism. Overall, the power of the cogenerative dialogue, in all it simplicity, is vital to the coteaching process and extremely powerful in the development of professional teaching. [20]

Coteaching as a student teaching model offers many practical and ethical advantages over traditional models but faces obstacles in actual implementation. It is evident from the work of GALLO-FOX et al. that the large amount of people involved in the process makes communication in general very difficult and open to ethical issues. Without clear goals, expectations, and lines of communication between all those involved coteaching can easily transform to more familiar and comfortable strategies. It is vital in the process of coteaching to include authentic attempts of cogenerative dialoguing, as this praxis leads to more complete understandings of responsibility and opportunities for opinions to be expressed without fear of repercussion. [21]

Work on this article was made possible by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (to Wolff-Michael ROTH).

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1993). Toward a philosophy of the act. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Engeström, Yrjö (1993). Developmental studies of work as a testbench of activity theory: the case of primary care medical practice. In Seth Chaiklin & Jean Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context (pp.64-103) Cambridge University Press.

Gallo-Fox, Jennifer; Wassell, Beth; Scantlebury, Kathryn & Juck, Matthew (2006). Warts and all: Ethical dilemmas in implementing the coteaching model. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 18. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/4-06/06-4-18-e.htm.

Leont'ev, Alexei N. (1978). Activity, consciousness and personality. Englewood Cliffs, CA: Prentice Hall.

Leont'ev, Alexei N. (1981). Problems of the development of the mind. Moscow: Progress.

Levinas, Emmanuel (1998). Otherwise than being or beyond essence (Alphonso Lingis, Trans.). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. (Original work published 1974).

Nancy, Jean-Luc (2000). Being singular plural. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ricœur, Paul (1992). Oneself as another. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roth, Wolff-Michael, & Tobin, Kenneth (2002). At the elbow of another: Learning to teach by coteaching. New York: Peter Lang.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Tobin, Ken (2004). Cogenerative dialoguing and metaloguing: Reflexivity of processes and genres. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(3), Art. 7. http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-7-e.htm.

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Tobin, Kenneth, & Zimmerman, Andrea (2002). Coteaching/cogenerative dialoguing: Learning environments research as classroom praxis. Learning Environments Research, 5, 1-28.

Tillman, Linda C. (2003). Mentoring, reflection, and reciprocal journaling. Theory Into Practice, 42, 226–233.

Tobin, Kenneth; Zurbano, Regina; Ford, Allison, & Carambo, Cristobel (2003). Learning to teach through coteaching and cogenerative dialogue. Cybernetics & Human Knowing, 10(2), 51-73.

Ian STITH is doctoral fellow in the Pacific Center for Scientific and Technological Literacy at the University of Victoria.

Contact:

Ian Stith

MacLaurin Building A420, Department of Curriculum and Instruction

University of Victoria, Victoria, BC V8W 3N4

Canada

Phone: 1-250-721-7834

E-mail: ianstith@uvic.ca

Stith, Ian (2006). Responsibility and Coteaching: A Review of "Warts and All" [21 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), Art. 22, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0604228.