Volume 4, No. 3, Art. 22 – September 2003

Transformative Experiences of a Turkish Woman in Germany: A Case-Mediated Approach toward an Autobiographical Narrative Interview

Setsuo Mizuno

Abstract: By making use of the Case-Mediated (CM) Approach toward a particular text, major characteristics of transformative experiences of the individual in question (Hulya, a Turkish woman living in a German city) are elucidated. The key analytical procedures of this approach consist of six interrelated activities: 1) those of tracing and retracing, 2) generating, 3) expanding and linking, 4) clarifying, 5) checking, and 6) re-clarifying and re-configuring. Through the tracing and retracing of the text in question, three particular dates and five periods are identified, and potentially important expressions are recognized. The main characteristics of State 1, referring to the state Hulya had been in before coming to Germany, and those of State 2, that is, the state she was in at the time of interview, are presented in contrast. Taking into consideration such things as the episodes Hulya experienced, conscious moves that she made, and "value" and "illness" factors, several phases of transformation of State 1 into State 2 are suggested. Some implications of her reflective thoughts about what concerned her most at the time of the interview for the characterization of State 2 are also discussed.

Key words: autobiographical narrative interview, case-mediated (CM) approach, life orientation, periodization, potentially important expression, reflective thought, the theme of home, transformative experience

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: An Explanation of Analytical Procedures

1.1 Typical procedures of a case-mediated approach

1.2 The actual analytical and interpretive processes used

2. An Examination of Transformative Experiences of Hulya, a Turkish Woman Living in a German City

2.1 Two states contrasted

2.2 Tracing the processes of transformation of State 1 into State 2

2.3 Phase 1: The Istanbul experience

2.4 Phase 2a: Major characteristics of her early experiences in Germany

2.5 Phase 2b: Some changes in Hulya's life situation

2.6 Phase 3: "Return-to-Turkey" orientation and "individual" orientation

2.7 Phase 4: Post-adjustment in Germany or new beginnings for Hulya

3. Hulya's Reflective Thoughts

4. Concluding Remarks

1. Introduction: An Explanation of Analytical Procedures

My task here is to analyze and interpret in my own way the material called "A Narrative Interview with Hulya, a Turkish Woman Living in a German City." The basic perspective adopted here is that of exploring what I call the phenomenon of the individual, meaning the elucidation of major characteristics concerning the individual in question (in this case, Hulya). Before going into a detailed examination of this material from this basic perspective, let me first explain two points. One is my basic policy about how to approach the material in question, and the other is an explanation of the actual analytical and interpretive processes used. In other words, I would like to summarize the particular analytical and interpretive standpoints that I have adopted as well as the specific analytical and interpretive activities that I have engaged in while examining the above text. [1]

1.1 Typical procedures of a case-mediated approach

My analytical method is what I call a Case-Mediated Approach toward particular material (MIZUNO, 2000). This approach has the following characteristics: it (a) identifies the case for some research objective, (b) proposes a particular understanding of the case in question as the primary task, and (c) attempts to approach indirectly the research objective as we accomplish this task. The main analytical procedures of this approach consist of six interrelated activities: 1) tracing and retracing, 2) generating, 3) expanding and linking, 4) clarifying, 5) checking, and 6) re-clarifying and re-configuring. [2]

Tracing and retracing refer to a careful and minute reading and rereading of the text in question in order to facilitate better understanding of what the analyst regards as major characteristics of the text, such as the main plots, phases, processes, components, and so forth. This activity is a basic way of familiarizing oneself with unfamiliar or less familiar material. I consider it very important that we explicitly situate this kind of familiarization and deeper understanding of the material in question as the first analytical and interpretive step. [3]

Generating refers to the generation of ideas, momentary impressions, perspectives, and so forth. We engage in this activity in parallel with that of tracing and retracing, and it occupies a very important position in beginning the analysis and interpretation of the material. Here the momentary impressions as well as whatever else comes to the mind of the analyst have important implications for the progress of analysis and interpretation.1) I use the metaphor of a seismometer's needle to explain the importance of these thoughts while tracing and retracing the text in question. We occasionally come across passages where the needle is set in motion. Since these passages indicate that we might find something that is possibly significant, it is very important to our basic analytical stance to try to grasp and articulate the possible contents of that "something." Specifically it means the articulating activity which I call writing on-the-spot memos. That is, writing down at once whatever comes to one's mind. I believe this is one of the main activities Anselm STRAUSS, who has greatly influenced the development of my analytical skills, called open coding (STRAUSS, 1987). [4]

Expanding and linking refer to trial activities of expanding and linking, as well as elaborating, ideas and momentary impressions that had been produced through the generating activities mentioned above. These activities, I think, also correspond to what STRAUSS calls open coding or axial coding (STRAUSS, 1987). [5]

Clarifying refers to the clarification of the ideas and impressions that have been generated and elaborated. It does not matter much yet whether those ideas derived from the generating and expanding and linking phases are amorphous or not. It is the task of this phase to clarify and articulate those promising parts of the amorphous and ambiguous ideas—amorphous and ambiguous, that is, even to the person doing the analysis. [6]

What is important here is to objectify and formulate, as clearly as possible, what the analyst thinks are the central parts of the ideas in question. Even when there might be some errors in products of objectification and formulation, we should continue to engage in this activity, just reminding ourselves that we can correct these errors afterwards. [7]

Checking refers to checking the clarified ideas and impressions with the text in question so that we can be sure about the reliability of these impressions. In this connection we can consider the clarifying activity that I referred to above as a kind of presentation of a hypothesis, because practically speaking it represents the understanding of the ideas which occurred to oneself. In that case, checking might be regarded as the verification of such a hypothesis. [8]

Re-clarifying and re-configuring refer to the re-clarifying and re-configuring of ideas and impressions which had been through the checking process. As this activity is a revised version of objectified and formulated ideas and impressions, it is likely that these objectifications and formulations are better than those done in the clarifying phase. I would like to point out, however, that there is no guarantee that once is enough to perfect the revision. That is, even after re-clarifying and re-configuring, we should be prepared for some possible cases in which the formulated ideas might still contain errors of some kind. In these cases we have to begin again, sometimes repeatedly, the cycle of checking and then re-clarifying and re-configuring activities. [9]

1.2 The actual analytical and interpretive processes used

The following explains the actual analytical and interpretive processes used. I will begin by explicating the ideas that occurred to me during the tracing and retracing and generating phases. What I adopted as tentative analytical strategies were the ideas of periodization and the identification of potentially important (PI) expressions. [10]

Generally speaking, the idea of periodization involves determining some marking points which, from the analyst's point of view, seem to emerge when engaging in the chronological rearrangement of the material in question. Here it refers to the attempt to determine potential marking points for Hulya's life, which we infer by tracing the narrative of her own life experiences. Following this conception, I came to notice and identify three dates and five periods. [11]

The three dates here refer to, respectively, the date of Hulya's arrival in Germany (5 July 1972), the day when she switched to the lower paying job (28 May 1979), and the day when the interview was conducted (6 February 1986). [12]

What could we say about the situation of Turkish workers during the years, starting from Hulya's arrival in Germany in 1972 through 1979, in terms of Turkish migration to West Germany? In 1961, when the governments of West Germany and Turkey agreed to institute a formal migration system, the Turkish population in West Germany was just over 8,700. It began to increase rapidly, and by 1965 it was 72,476 and in 1974 it was more than 1 million (MOCH, 1992, p.186). Since late January 1972, Turkish workers have constituted the largest national contingent in the foreign work force in the Federal Republic of Germany (HERBERT, 1990, p.230). The year 1972 also belonged to the last phase of what is generally called the recruitment era (1960-1973) in the history of migration of foreign workers to West Germany. There was a recruitment halt in November 1973, which meant the end of the traditional methods of employment of foreign labor on a temporary basis (MOROKVASIC, 1984, p.888; ZLOTNIK, 1995, p.240; HERBERT, 1990, p.234, p.250). During this period, with its economic boom as a backdrop, only wage workers were allowed to enter the country. As German employers wanted unskilled, low-paid workers, single men and women were welcomed as the ideal workers (GOODMAN, 1987, p.215). Since the late 1960s, the number of women workers from Turkey increased, and after the recession of 1966-1967, about a third of Turkish immigrants were women (MOCH, 1992, p.187; ZLOTNIK, 1995, p.240). It was well known that there was a wide gap between Turkish and West German standards of living. In 1973, for example, the per capita income of Turks was $563.00, while that of West Germans was $3,739.00 (MOCH, 1992, p.186). Thus, Hulya entered West Germany as one of many low-paid women workers from Turkey, the experiential implications of which we will see later in Phase 2a. [13]

The five periods are the products, in terms of periodization, of the articulation of the material in question. The following are the periods that I could identify:

Period 1: before coming to Germany (ll.122-258; the numbers here refer to the line numbers of the transcription of the Hulya interview available in the Internet as http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-03/Huelya-e.htm. So ll.122-258 means line 122 through line 258 of the transcription.)

Period 2: from the day she arrived in Germany through the first year (ll.260-475)

Period 3: from the second year through the fourth year in Germany (ll.477-544)

Period 4a: from the day she got married during her vacation in her fourth year in Germany through the day when she changed jobs for a lower paying but more suitable one (ll.546-812)

Period 4b: from the day she got married through the day when her divorce was finalized (ll.546-812)

Period 5a: from when she changed jobs through the time when her first narrative came to an end by saying "Well, that's my story." (ll.814-844)

Period 5b: from the end of her first narrative through the end of the interview, during which she gave various comments, looking back on her whole life (ll.846-1063) [14]

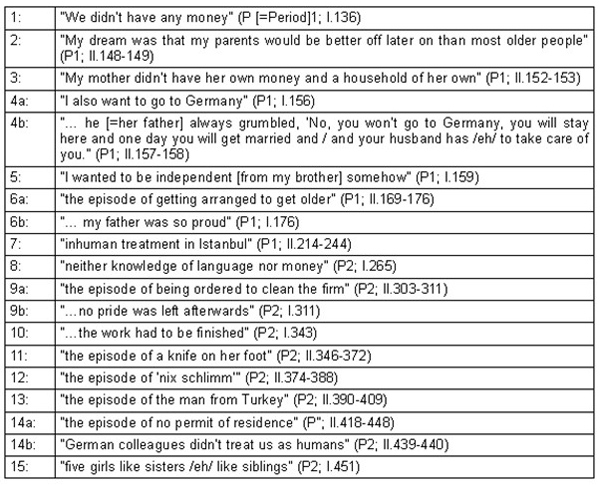

As for the idea of identifying PI expressions, this essentially refers to making a list of their occurrences in the text. At the end of each item the period in question and the page number are inserted (see Table 1).

Table 1: List of Potentially Important (PI) Expressions (extract) [15]

Two additional ideas came to my mind while working on the data. First was the idea of contrasting two states: the state in the beginning, or State 1, meaning the state Hulya had been in before coming to Germany, in contrast to State 2, the state she was in at the time of her interview. Second was the idea of tracing how State 1 was transformed into State 2. At this analytical point I could visualize a general scenario for the period from the very beginning of the interview through the moment when she ended the first narrative with the following remark: "Well, that's my story. That's the whole life." (l.843) [16]

After a series of detailed analyses of the material, I decided to examine Period 5b in terms of an overall review of Hulya's life from the point of view of her current reflective thoughts about what had happened and what the future holds. Also in this case, the accumulated items listed as potentially important expressions provided me with very important suggestions. [17]

On the basis of the above exploration of the processes, I would like to make a more detailed examination of the notion of contrasting the two states as well as the transformative processes. [18]

2. An Examination of Transformative Experiences of Hulya, a Turkish Woman Living in a German City

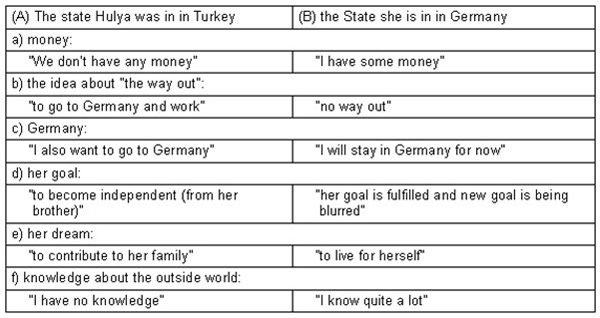

Being presented as a retrospective, the text seems to reveal a wide gap between Hulya's way of thinking before coming to Germany and her way of thinking at the time of the interview. We can get a glimpse of this gap from remarks such as: "I would have done it earlier, fifteen years ago, but today where I've taken care of myself for so long and have been my own boss, well ... I'd rather take my life /eh/ instead of living dependently /eh/, that means: I cannot do it any more" (ll.890-892). I would like to make this contrast more explicit. First, pick out conspicuous passages from Hulya's remarks in Period 1, especially passages from the first half of the period, and then explore the corresponding ones in her remarks in Period 5b. Let me elucidate this contrast with the following six aspects: a) money, b) the idea about "the way out," c) Germany, d) her goal, e) her dream, and f) knowledge of the outside world. Table 2 shows the differences of the two states in terms of these aspects.

Table 2: Two States Contrasted [19]

The following are what I take to be major characteristics of State 1, the state Hulya was in before coming to Germany: During this period Hulya took her way of thinking as a family member for granted. Therefore, she recognized her family situation after the illness of her father as a "no money" situation, which symbolizes their poverty (aspect a), while going to Germany to work was conceived as the solution (aspect b). In addition, going to Germany was both her personal desire (aspect c), and a powerful means to move toward independence, especially from her brother (aspect d). Her dream of going to Germany also had the character of the dream conceived as a family member (aspect e). This family-oriented conception was based on the fact that she was living in a closed information network of Turkish society, deeply immersed in its customs and its ways of thinking, without any knowledge of the "outside world" (aspect f). [20]

What was Hulya's state at the time of the interview? At this point in time she has some money (aspect a), and intends to stay in Germany as long as there is a place for her to work (aspect c). Her orientation toward financial and mental independence is being realized for now, but in contrast with the realization of such everyday goals, her fundamental life goals are being blurred (aspect d). Now her dream is not to live as a family member, but to live for herself (aspect e). Given Hulya's present understanding, which is based on the knowledge of the "outside world" of both Turkish and German societies (aspect f), she cannot help but regard her own present situation as a divorced woman as the one with very few options (aspect b). [21]

2.2 Tracing the processes of transformation of State 1 into State 2

Now we examine how State 1, the state Hulya had been in before coming to Germany, was transformed into State 2, the state she was in at the time of the interview. When taking into consideration the episodes Hulya experienced, her intentional moves, her own view of value, and unexpected happenings such as her illness and multiple surgeries, we can trace her transformative processes by distinguishing the following four phases. [22]

Phase 1 (ll.213-258) represents Hulya's Istanbul experience. For the first time in her life she went to Istanbul, a big city, with her brother to go through the emigration procedures, which took four days. In this process she was already forced to face intercultural experiences and the clash of heterogeneous values contained in them. [23]

Phase 2 (ll.260-544) depicts Hulya's early experiences in Germany, which we could divide into phase 2a, the first year in Germany and phase 2b, the second through the fourth year in Germany. Her primary German experiences were concentrated in phase 2a. [24]

Phase 3 (ll.546-739) portrays the coexistence of two orientations in Hulya, the main tendency being a shift from a "Return-To-Turkey" orientation to an "Individual" orientation. Here we can observe her move to get married, unexpected events which befall her (such as an abrupt illness and three consecutive surgeries), being pushed by a strong longing for "home," her move to go back to her mother first instead of to her husband, and the divorce that followed. [25]

Phase 4 (ll.741-812) illustrates Hulya's post-adjustment in Germany. After deciding to stay in Germany, she began to make positive moves in various ways. [26]

Next I will examine each of these four phases in greater detail. [27]

2.3 Phase 1: The Istanbul experience

What is conspicuous in this phase is her experience of culture shock during the examination for the emigration procedures. She succinctly expresses this point when she says, "In Istanbul we were just a number, not a personality any more" (l.219). She was experiencing here the clash of the values rooted in the culture in which she was born and raised with a heterogeneous and alienating culture in which everything was thought of in terms of numbers. (The former value should be consonant with the value of "sticking together," the importance of which she would come to realize in phase 2.) The inhuman treatment Hulya experienced here was the very thing which foreshadowed what she would come to experience later in Germany, and yet she felt there was no other way of getting out of poverty. She described the situation as "the only way out" (l.236); that she had to go through the examination even though it meant being exposed to such humiliating experiences. [28]

2.4 Phase 2a: Major characteristics of her early experiences in Germany

We can note the following six points as the characteristics of Phase 2a. The first is the situation Hulya was thrown into after her arrival in Germany: she had no money, no language ability, and no knowledge of local customs (ll.263-265). The second is the unimaginably humiliating working conditions that Hulya had to endure everyday for a year. That is, what awaited her was not only normal packaging work, which was hard enough, but also the extra cleaning work, which she hated. It had a humiliating and degrading affect upon her, because she knew that no one in Turkey would have stood for it, yet she was forced to do it. So "no pride was left afterwards" (l.311). As a third point, we can refer to the four episodes which symbolize the severity of her working conditions: that of "a knife on her foot" (ll.346-372); that of "nix schlimm (not tragic)" (ll.374-388); that of "the man from Turkey" (ll.390-409); that of "no permit of residence" (ll.418-448). The fourth point is the work of environmental mechanisms that can be glimpsed in these episodes. What the first episode of a knife on her foot suggests, for example, is the structural inadequacy of the welfare system for those on the factory floor or on the company level, or both. It implies that by taking advantage of the language difficulties, the welfare system can leave the employee's injuries untreated when they should have some kind of backup system to take care of them. The second episode refers to an accident involving Hulya, a consequence of which her hand was injured. She showed it to her chief operator but he responded by saying it was not tragic. The implication of this second episode is that it appears to be a system in which a chief operator can get away with such irresponsible remarks. From the third episode we can infer both the company's nature: they hide from view what they don't want to be revealed, and the nature of the public official sent from Turkey who simply enjoys the reception from the company and does not have the sense of responsibility to perform his duty. The fourth episode reveals the nature of the company when its management allows the immigrant workers' residence permits to expire. In other words, these episodes illustrate the operating mechanisms of this company, which, without any regulation of work hours, does not mind stripping its employees of their rights. When compared with the relevant literature in the field of Turkish migration research, Hulya's working experiences in this company were amazingly similar to the descriptions of other Turkish migrant workers (MUENSCHER 1984, p.1232). Also her experiences seem to be in line with the trends that have traditionally characterized foreign labor since the 1880s (HERBERT 1990, p.230; see also p. 246). The fifth point is that, fortunately enough, Hulya's interpersonal environment was a highly positive one, which embodied the value of sticking together: "five girls like sisters /eh/ like siblings" (l.451) was Hulya's description of this environment. The sixth point is the fact that Hulya was working in a system that forced her to work extremely hard, as is symbolized by the episode in which, because of her weight loss from 70 kilograms to 50 kilograms, no one in Hulya's home town could recognize her at first when she returned (ll.528-529; ll.550-551). [29]

2.5 Phase 2b: Some changes in Hulya's life situation

Two changes occurred during Phase 2b. One is the change in Hulya's working conditions: She got "a job in a metal processing firm" (l.480). The work there was shift work, which was not as hard as the work in Phase 2a, but still the "work [was] not easy" (l.488). The other is the change in her living conditions, the experience of which contributed to the re-affirmation of her own value mentioned above. After having lived for the first four years in Germany with four other young women, she moved into a company dormitory. This dormitory, when seen as her living environment, was "not so nice" (l.501). This was due, in part, to the difficulties arising from age differences among the women (ll.507-510) and also to the fact that she could not find the interpersonal atmosphere of "sticking together" (l.514). [30]

Two additional points seem to be relevant to the importance Hulya places on "sticking together." The first point is that Hulya evaluated this so highly that the threat to it had a deeply felt emotional effect on her own personality (ll.515-523). The second point is the interesting fact that Hulya's relatives in Germany were not a group of people with whom she could feel like getting along, even though according to Turkish traditions they should have been a group she would have stayed close to (ll.531-532). [31]

The main consequence of her German experiences in Phase 2b is what might be called her "Return-To-Turkey" orientation, which is symbolized by her remarks, given while looking back on this period: "I didn't want to return to Germany. I wanted to go back to Turkey." (ll.546-547). These remarks signaled that she was about to enter Phase 3. [32]

2.6 Phase 3: "Return-to-Turkey" orientation and "individual" orientation

While Hulya's move toward getting married could be read as a manifestation of her own "Return-To-Turkey" orientation, fitting in well with a short-term migration pattern, it also proved to be the first move that started to determine the shape of her present situation. My reading is that the beginning of this first move had originated in her wish "to go back to Germany again, for a while" (l.565), which she proposed as a precondition for her marriage. This precondition turned out to be the very cause of structural conflicts between Hulya and her husband, who lived in Turkey. [33]

After her marriage, Hulya came back to Germany, promising to return to Turkey in one year. What she encountered was one unexpected event after another, which, in my judgment, was the result of the accumulated effects of chronic overwork during Phase 2. In this period Hulya suffered an abrupt illness and went through three consecutive surgeries. During her second operation, Hulya was forced to make a crucial decision regarding her own way of life. At this point she decided that "my life was more important for me" (ll.607-608). We can see here the first manifestation of her "individual" orientation, which is contradictory to the typical "family" orientation she had apparently kept so far. Hulya's life in the hospital came to generate two additional negative experiences which contributed to the further strengthening of the individual orientation as her basic life policy. One is related to the fact that "I [Hulya] had to do everything on my own" (l.633) during her critical and life-threatening period. She complained that no one was available to help her (ll.633-636). What she had on her mind here was the lack of help given by her fellow Turks (ll.634-635) around her. Taking into account the fact that Hulya was married at that time, however, it is likely that she also may have included her own husband as one of those who did not help her. The other experience was the feeling of "I am alone and no one comes by" (l.656) when she most wanted whatever psychological support she could get. These two negative experiences seemed to have forced Hulya to the conviction that there was no one else to rely on but herself. In such a psychological state her longing for her home increased in intensity. Being pushed by the feeling that "I urgently wanted to go home" (l.673), Hulya did make the second move that determined her current state, which was going to her mother first, not to her husband (l.686; l.690). By this particular move her own longing for her home was fulfilled, although since this was also the very act by which "her husband and his family felt insulted" (ll.694-695), it is likely that it turned out be a crucial move, leading eventually to their divorce. After this episode the structural conflicts between Hulya and her husband, which were present prior to this incident, appeared to become more serious. [34]

2.7 Phase 4: Post-adjustment in Germany or new beginnings for Hulya

After deciding to stay in Germany, Hulya appeared to make determined efforts in three ways. The first way was her move to fight in the labor court (ll.741-742). From her remark "I have to do all of this by myself. I have to get my experiences." (l.742) It appears that this move represented a new beginning for Hulya. The second way was Hulya's move to overcome her language handicap. She did this by the strategy of learning German through television (ll.746-750). The third way was the move of "finding a job on my own" (l.790). We have here a very active and independence-seeking image of Hulya, who, while clinging to her work, endured the pain by clenching her teeth and telling herself such self-suggestive and self-encouraging words as "If you want to, you can do everything." (l.792). After five months Hulya decided to give up this work, acknowledging that "No, I can't do that." (l.800) [35]

3. Hulya's Reflective Thoughts

What I call here "Hulya's reflective thoughts" are her remarks made in the last section of the interview, starting with line 846. Here I would like to point out three major interrelated themes: 1) her life orientation, 2) what she evaluates highly, and 3) her mature perception of people's situation in Turkey and Germany. [36]

The first theme refers to those topics related to her way of living. First is the value given to money, an important factor leading to her emigration to Germany. Her present perception is that "Money is on the last place. But money is very important." (l.1039). Researchers in the field of migration research might question why there is no mention of the topic of remittance in this interview. It is a strange omission, indeed, which might have something to do with the format of the interview itself: the interview in question was an open-ended one, conducted only once, without any supplementary questions by the interviewers intentionally made concerning the topic of migration. [37]

What of the weight given to working in Germany? "When you have to work, as long as you have to work, you will stay in Germany. If you're allowed." (ll.1042-1043) is Hulya's response to this question. [38]

Since Hulya has decided to stay and continue working in Germany until she feels assured that she can lead a financially independent life in Turkey, for the time being it seems going back is unthinkable, especially going back to Turkish ways of doing things. In that sense she is leading a life cut off from her past. Therefore, when she goes back to Turkey and visits her relatives, she cannot help but feel that she is just a guest there (l.878; l.899), and that there is a significant difference between now and then; that is, 15 years ago when she left Turkey (ll.887-893). Such feelings are supported by her belief that "I fully, I've had contact with the outer world, I've had contact with people, I know more about the world." (ll.926-927) [39]

In addition, as a divorced single woman Hulya is well aware of the difficulties such women have to endure in Turkey and understands that she has few options if she were to go back (ll.907-921; MUENSCHER, 1984, p.1245). [40]

What kind of life does she want to lead? Hulya's basic perspective is "to live not for others but for herself" (l.1058), which Hulya learned to adopt as her principle for living by enduring a series of severe experiences. Partly because of such circumstances as the instability derived from her working conditions and being exposed to the constricted options of a divorced Turkish woman, Hulya's existential situation is hardly a stable one, as we can infer from such remarks as: "... Under German conditions / ... I am still pretty young, you know. So I am still in the /eh/ beginning of my life, but I feel like ... ninety or empty, nothing, no ideals and no aim. Sometimes /eh/ I don't see any meaning in living like that." (ll.852-855). She seems to be suffering, once in a while, from a sense of emptiness about her present life situation. And yet she is also a person who is trying to live her life more positively with some future orientation, which she expresses by saying things such as "It might be that I will find someone when I am forty, you know, who also thinks like me, a man." (ll.1054-1055) [41]

The next theme I would like to discuss is what Hulya values highly. Three things seem to be important to her. The first is her orientation and wish to live for herself, which I referred to above in connection with the first theme. The second is the importance of sticking together, thanks to which she somehow managed to survive the most difficult periods. The third is what she calls home. [42]

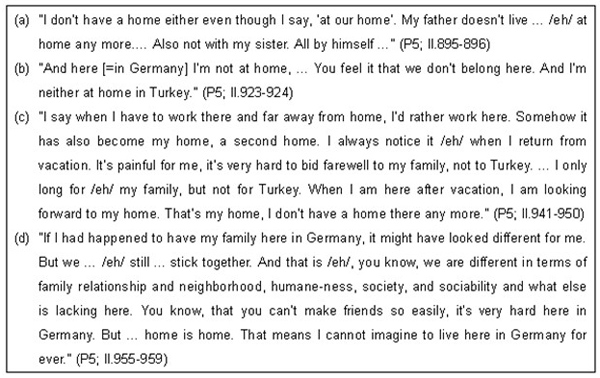

Taking into account her complicated remarks concerning the word "home" (see Table 3), I would like to think about possible meanings of home for Hulya. (When I say that her remarks are complicated, I am thinking of the following four remarks in Table 3: (a) and (c), which seem to reveal different understandings of the placement of family in connection with home, and the remarks (c) and (d), which indicate contradictory evaluations of Turkey.)

Table 3: Passages Related to the Theme of Home [43]

We have already seen that Hulya has a strong longing for home and that, when being pushed by this emotional imagery of home, she sometimes behaves unexpectedly, even to herself. For example, by taking a long return trip to her mother in Turkey that, because of her illness, was prohibited by her doctor. It seems that there are happy childhood memories behind her longing for home, which we can see from her remark: "Of course, I still have this beautiful picture of my childhood in my mind, you know, and I dream of former days. I am living of my past ..." (ll.900-902). From remark (d) in Table 3 we can infer that these childhood memories seem to be related to the value of sticking together, mentioned above as the second item she regards as important. [44]

In connection with the theme of home, Hulya repeatedly laments that in her present situation she cannot have one and, what is more, no home can be found either in Germany or in Turkey. The reason she cannot have a home in Germany is that in leading her everyday life Hulya is reminded that "we (meaning her and her fellow Turks) don't belong here" (ll.923-924). She is probably thinking of everyday experiences peppered with racial discrimination. The reason why she cannot have a home in Turkey is that her family in Turkey is virtually broken apart—or taking into account the remark (c) in Table 3, it might be more accurate to say that this perception is being emphasized here. [45]

We should not forget, however, that even in the present situation there are exceptional cases in which Hulya can feel at home, or more accurately, cases in which she can feel sure that this is her home. She has this special feeling, for example, when she is in her own living space in Germany on her return from vacation (remark (c), Table 3). Next is the time when the topic about some positive Turkish values—from Hulya's perspective—come up. According to my reading, when she uses the expression "home is home" (l.959), the home referred to includes Turkey. Nevertheless, in this context it is not the real Turkey, which excludes divorced women, but an imagined Turkey, which embodies the value of sticking together, with this imagined Turkey existing primarily in her happy childhood memories. The value of sticking together is here characterized as the existence of humane connected-ness, such as "family relationship and ... neighborhood, humane-ness, society, and sociability" (l.957). Hulya seems to dislike Turkey and cannot help but feel alienated from it, but still she goes back to Turkey once in a while, the major reason being to visit her family as their guest. Even though Hulya confesses that she does not feel at home with them, the time when she visits them might be counted, to some degree, as being at home for her. [46]

In summary, while the real Germany, the real Turkey, and Hulya's life today as a family member in her real Turkish family cannot be her home, what can be her home are her own living space in Germany after vacation, Turkey as she imagined it, and her real Turkish family, as long as she visits them as their guest. [47]

The last theme is that of Hulya's mature perception of people's situation in Turkey and Germany, including their ways of thinking and behaving. On the one hand, she seems to be being exposed to subtle racial discrimination in her everyday life. Her remarks such as "... how terrible it /ehm/ is: to be frowned upon by people in the streets all the time" (ll.846-847) and "People are not all bad.... But if one generalizes, if one says more generally, 'All Turks bad,' that's what makes me angry" (ll.861-862) suggests Hulya's repeated encounters with stereotypical ways of thinking and behaviors about superficial differences between Turkey and Germany. On the other hand, when it comes to people's ways of thinking and behaving, Hulya has a basic understanding that there is no qualitative difference between Turkey and Germany. Hulya has the calm perception that the situation in Turkey is "worse but not different" (l.985) from that in Germany. The very fact that she has this kind of mature and flexible perception might be related to her feminist orientation (ll.985-1032), which she must have incorporated during the period when she had been gaining her initiative and individual orientation. [48]

I would like to conclude this paper by referring to two critical topics. One topic is related to the limitation of my analysis. As I noted above, there are several important topics in the interview in question which Hulya either left unsaid or did not fully elaborate, such as the death of her mother, the topic of remittance (MOROKVASIC, 1984, p.893, p.896), the details of marriage and divorce, and the reasons for her complaints about her own self-sacrifices. These omissions and under-representations seem to reveal the quality as well as the limitations of these particular interview data, constraining my method of analysis, with the main analytical targets being limited to what TREICHEL and SCHWELLING (1998) aptly and negatively phrased as "understanding only the understandable" (p.14). In other words, what I tried to do in this paper is to show how far we can go when we remain on the level of understanding only the understandable. [49]

The other topic is Hulya's two remarks made when referring to the former part of Period 1, that is, the period before coming to Germany, which we can regard, in a way, as summary statements concerning her present situation. One is her perception of her mother's situation: "... she [her mother] practically didn't have her own money and not a household of her own when my father became ill" (ll.152-154). The other is: "No, you won't go to Germany, you will stay here and one day you will get married and / and your husband has /eh/ to take care of you." (ll.157-158). These are her father's grumbling words to Hulya, who begged him to let her go to Germany. We can easily see that her present situation is just the opposite of these remarks. [50]

This English version was written with the cooperation of Mr. Lang CRAIGHILL. I very much appreciate his help in improving my original English draft. I also appreciate meticulous comments and modifications by Robert FAUX. This work was supported by MEXT.KAKENHI (15530343).

1) Let me explain the connection between the basic analytical perspective mentioned above and the momentary impressions in the generating activity. My basic understanding is that, whether the analyst is well aware of his or her analytical perspective or not, these momentary impressions in the generating activity tend to emerge through the analyst's interaction with the material in question. In other words, while the existence of some analytical perspective or other is logically required as a precondition in order to make the material into meaningful data, it is not necessary for the analyst to be aware of his or her perspective before he or she begins to analyze. So in the analysis of the material in question, one could have a clear analytical perspective beforehand, of course, but there are those perspectives that one comes to grasp and realize later through the struggle with the material in question. The latter perspectives are the ones that are supposed to be derived from the momentary impressions in the generating activity. <back>

Abadan-Unat, Nermin (1977). Implications of Migration on Emancipation and Pseudo-Emancipation of Turkish Women. International Migration Review, XI(1), 31-57.

Goodman, Charity (1987). A Day in the Life of a Single Spanish Woman in West Germany. In Hans Christian Buechler & Judith-Maria Buechler (Eds.), Migrants in Europe: The Role of Family, Labor, and Politics (pp.207-219). New York: Greenwood Press.

Herbert, Ulrich (1990). A History of Foreign Labor in Germany, 1880-1980: Seasonal Workers/Forced Laborers Guest Workers. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Mizuno, Setsuo (2000). Jirei-Bunseki eno Chousen [(in Japanese); Challenge of Case Analyses: A Case-Mediated Approach Toward the Phenomena called "the Person" ]. Tokyo: Toshindo.

Moch, Leslie Page (1992). Moving Europeans: Migration in Western Europe since 1650. Bloomington & Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press.

Morokvasic, Mirjana (1984). Birds of Passage are also Women ... International Migration Review, XVIII(4), 886-907.

Muenscher, Alice (1984). The Workday Routines of Turkish Women in Federal Republic of Germany: Results of a Pilot Study. International Migration Review, XVIII(4), 1230-1246.

Strauss, Anselm (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press.

Treichel, Bärbel & Schwelling, Birgit (2003). Extended Processes of Biographical Suffering and the Allusive Expression of Deceit in an Autobiographical Narrative Interview with a Female Migrant Worker in Germany [65 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 4(3), Art. 24. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-03/3-03treichelschwelling-e.htm.

Yuecel, Ersan A. (1987). Turkish Migrant Workers in the Federal Republic of Germany: A Case Study. In Hans Christian Buechler & Judith-Maria Buechler (Eds.), Migrants in Europe: The Role of Family, Labor, and Politics (pp.117-148). New York: Greenwood Press.

Zlotnik, Hania (1995). The South-to-North Migration of Women. International Migration Review, XXIX(1), 229-254.

Mr. Setsuo MIZUNO is a professor of social psychology at the Faculty of Social Sciences at Hosei University, in Tokyo, Japan. Main research fields: life historical research; developments of specific techniques of qualitative analysis.

Contact:

Mr. Setsuo Mizuno

Faculty of Social Sciences at Hosei University

4342 Aihara-machi

Machida-shi, Tokyo

Japan

Phone: +81-42-322-5376

Fax: +81-42-322-5376

E-mail: smizuno@mt.tama.hosei.ac.jp

Mizuno, Setsuo (2003). Transformative Experiences of A Turkish Woman in Germany: A Case-Mediated Approach Toward An Autobiographical Narrative Interview [50 paragraphs].Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(3), Art. 22, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0303220.